Off-Grid Solar’s Killer App

Solar pumps, batteries, and microcredit are triggering an African agricultural renaissance

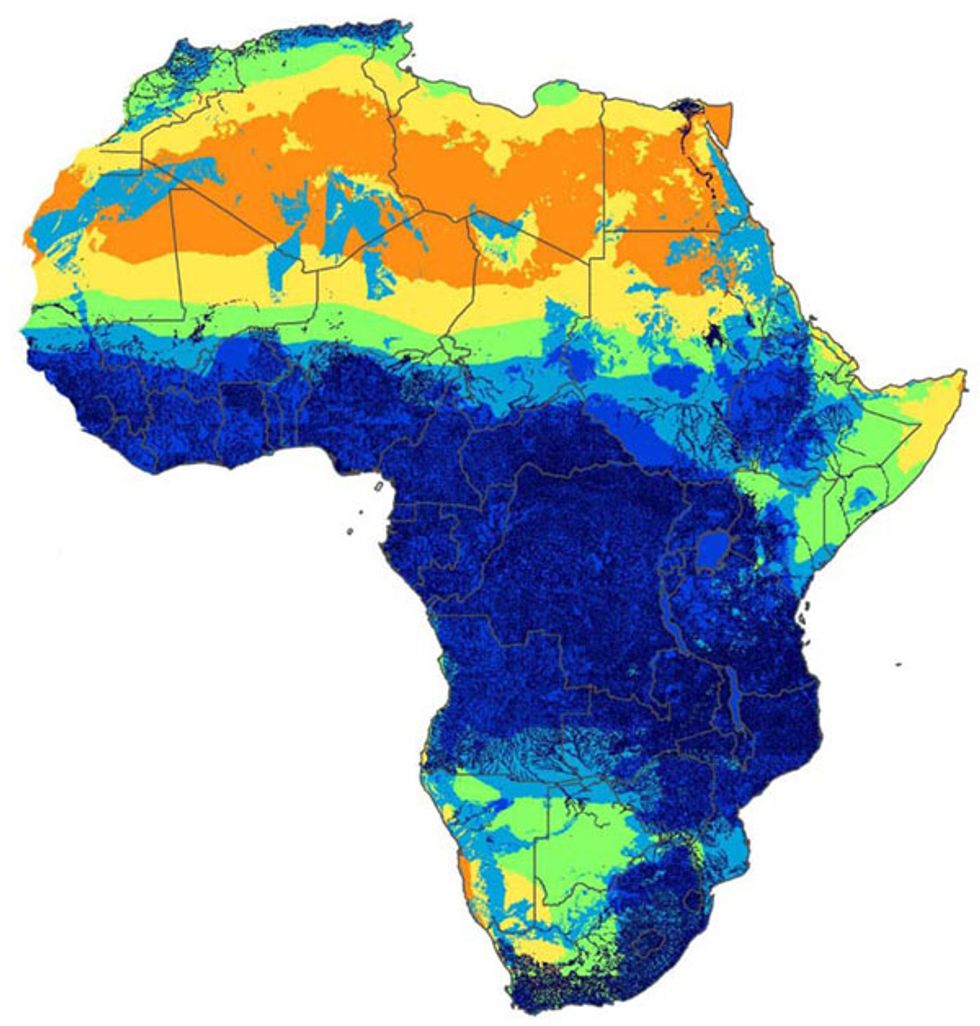

Kenya has the highest penetration of off-grid solar systems in Africa. Farmers in the region are gaining access to a number of solar-powered devices, including irrigation pumps, egg incubators, grain processors, and refrigerators.

It's a baking-hot February day in Matanya, a village that straddles the equator, a few hours' drive north of Nairobi. Smiling broadly, Patrick Gicheru is sowing carrots in layers of soil and compost at his 0.8-hectare farm and recalling a profitable crop of peppers that recently came from the same field. Tomatoes maturing on another plot should be ready for market in a month. “Tomatoes are going for about 80 shillings per kilo," he says. He estimates the crop will fetch him roughly 10,000 Kenyan shillings—a little over US $93—every week for nearly three months.

This year's tomato harvest alone will nearly pay for the technology that's underpinning Gicheru's success: a solar-powered water pump. A model of simplicity, it consists of a 310-watt photovoltaic panel, a 440-watt-hour lithium-ion battery pack, and a controller that supports his 3,000-liter-per-hour direct-current pump as well as a few LED lights, a mobile phone charger, and a flat-screen TV.

In February 2020, when I visited Gicheru, the small farmer had zero control over the COVID-19 pandemic that was spreading toward Kenya, or the historic locust invasion devouring fields throughout East Africa. But the solar pump he acquired in 2019 was tapping a stable supply of groundwater, boosting his yields and growing seasons, and neutralizing the waves of drought that have afflicted sub-Saharan Africa since time immemorial.

Before acquiring his solar system, Gicheru—like the vast majority of Kenya's small farmers—relied exclusively on rainfall. He also raised cattle back then and lost many to dry spells. He describes life with solar-powered irrigation as a new era: “It has really transformed our lives. At the end of the day, I can be able to put food on the table. I'm also employing people, so I can help them put food on the table. So I thank God. I'm happy."

It's a transformation that, if widely replicated, could radically improve the livelihoods of millions of people across Africa. According to a 2020 report from the International Finance Corp., an arm of the World Bank, more than 43 million small farmers in sub-Saharan Africa aren't connected to the power grid. Many of these farmers, like Gicheru, live above near-surface aquifers, yet they lack the means to tap the water. As a result, they remain vulnerable to crop failures, even though water might be literally meters away. And as struggling farmers give up their land and flee to the cities, the migration drives the continent's unchecked urbanization and dependence on food imports.

“Despite having the very tools for their escape from poverty—which are water, land, and sun—they're the most underserved people in the world," says Samir Ibrahim. He's the CEO and cofounder of Nairobi-based SunCulture, which is now Africa's leading solar-irrigation developer. Gicheru is one of the company's satisfied customers.

Ibrahim and Charles Nichols, SunCulture's cofounder and until recently its chief technology officer, have been perfecting their technology since starting the company in 2012. Now they say they're ready to scale up. Plummeting solar and battery prices have slashed hardware costs. New digital financing tools are making it easier for farmers to buy in. And innovative farming techniques promise to minimize water consumption—a crucial safeguard to ensure that the solar-irrigation boom they aim to unleash doesn't run dry.

The potential upside of solar irrigation could be huge, Ibrahim says. Solar pumps for small farmers could be a $1 billion market in Kenya alone, he notes. What's more, they could spark a virtuous cycle of rising productivity and access to capital. “If we can figure out how to make these farmers' incomes predictable and dependable, we can then give them access to commercial capital markets, and then we create an entirely new consumer market, and then we can sell into that consumer market," says Ibrahim.

That's a big dream, but it's one that Ibrahim, Nichols, and many others now believe is within reach.

SunCulture grew out of an idea that Ibrahim and Nichols hatched in 2011, when both were still college students in New York City. Seeing the rise in off-grid solar technology, they discussed building a solar business around enhancing the productivity of small farmers. They submitted their idea to a business-plan competition at New York University, where Ibrahim was majoring in business. Nichols had studied mechanical engineering at Stevens Institute of Technology and moved on to economics at Baruch College. Their proposal won the competition's “audience choice" award that year. By the end of 2012, they had moved to Kenya and were setting up the firm.

Nairobi, Kenya's capital, was a natural choice. A growing tech hub there had earned the city of 5 million its Silicon Savannah moniker. The city is also the epicenter of Africa's off-grid solar sector, and Kenya has the highest penetration of off-grid solar systems in Africa. There was also a personal connection: Ibrahim is the son of a Kenyan mother and a Tanzanian father.

Still, it took several years for Nichols and Ibrahim's solar-irrigation plan to gain traction. Incumbent players in the water-pumping business didn't take solar seriously, and investors doubted that small farmers would be able to afford it. “Everybody thought we were nuts. Nobody wanted to fund us," recalls Nichols.

Eight years and four major design iterations later, SunCulture is selling a robust system for about $950—less than one-fifth the price of its first product. The package combines solar-energy equipment with a pump and four LED lights and supports an optional TV. The pump is designed to tap water from as deep as 30 meters and irrigate a 0.4-hectare plot.

Nichols says the company's key hardware breakthrough was to include a battery. Most solar pumping systems, including SunCulture's early offerings, employ a water-storage tank that can be filled only when the sun is strong enough to run the pump. Nixing the tank and adding a battery instead created a stable power supply that customers could use to pump and irrigate on their own schedules. The battery can also charge in the early morning and late afternoon when the sunlight is too weak to run the pump directly.

SunCulture's partners supply the batteries, photovoltaic panels, and screw pumps driven by high-efficiency brushless DC motors. The company's core intellectual property lies in the printed circuit board for its integrated controller, communications, and battery base unit, designed by the company's senior electrical engineer Bogdan Patlun and his Ukraine-based team.

SunCulture uses a pay-as-you-go financing model, which has become popular in the off-grid solar sector. Rather than paying the full price up front, farmers put down a small deposit and then make monthly payments over several years. Gicheru put down 8,900 shillings for his system (about US $83) and is paying the remainder over 2.5 years at a rate of 3,900 shillings per month. It's a low-risk scheme for SunCulture because its electronics let the company remotely disable the equipment if a customer stops paying. By SunCulture's estimates, its “pay-as-you-grow" financing puts the company's system within reach of the majority of Kenya's 2 million small farmers who have access to water.

Those who choose to invest quickly see returns, according to a recent report by Dalberg Global Development Advisors, a consultancy headquartered in Geneva. Dalberg estimates that on small farms, solar irrigation improves yields by two to four times and incomes by two to six times. As a result, the report projects that 103,000 solar water pumps will be sold in Kenya over the next five years, up from fewer than 10,000 per year in 2019 and 2020. “The business case for irrigation is very strong," says Dalberg senior manager Michael Tweed.

The off-grid solar business needs products like SunCulture's pumps to free it from a productivity slump. The sector initially took off in the early 2000s by combining small commodity PV panels, batteries, and LED lights, creating a package that replaced comparatively costly—and dirty—kerosene lamps. Systems quickly expanded to include cellphone charging, which in turn boosted access to mobile banking, messaging, and the Internet. But over the past decade or so, the most popular new capabilities that off-grid solar has added are televisions and fans.

The focus on such lifestyle upgrades, as pleasant as they are for the owners, has prompted some economists to question the development impact of off-grid solar. “It's hard to imagine that watching TV or running a fan would actually make you significantly more productive, and therefore they don't break you out of the poverty track," says Johannes Urpelainen, who runs the Initiative for Sustainable Energy Policy at Johns Hopkins University, in Baltimore. “They don't really solve the main problem."

Solar irrigation, by contrast, demonstrably pulls people up. In a recent update to SunCulture's supporters, Ibrahim touted solar pumping's impact during the COVID-19 pandemic. He cited a survey by impact measurement firm 60 Decibels, in which 88 percent of Kenyan farmers said they were worse off financially due to the pandemic. In stark contrast, Ibrahim noted, 81 percent of SunCulture's clients increased their farming revenue.

It's no wonder then that SunCulture is picking up some big backers, such as France's state-owned power company, Electricité de France, which provides power in some remote, rural overseas regions and provinces. And no surprise, either, that SunCulture is also picking up some competition.

To keep its momentum going, SunCulture is working hard to ensure its approach is sustainable, by looking for ways to cut the amount of water its farmers use. In 2012, a continent-wide survey by U.K. researchers shone a spotlight on Africa's abundant and shallow aquifers, which were found even in semiarid areas that receive little rainfall. Subsequent research on groundwater management across sub-Saharan Africa found that tapping these aquifers reduced crop failures and boosted rural incomes. However, the researchers also identified “moderate" impacts on water tables after just five years of small-scale irrigation, with declines of up to 4 meters over 40 percent of the study area in east Africa.

An insight into aquifer limits—and one way to avoid exceeding them—is on display at the farmstead of Monicah Riitho, about 2 kilometers from Patrick Gicheru's farm. Riitho cultivates a bounty of fruits, vegetables, and grains on her 1.2-hectare parcel. Like Gicheru, the mother of four says she's better off thanks to her SunCulture pump. But every day she turns it on, the water level in her 21-meter borehole drops out of reach after about 3 hours of use.

The water level always recovers overnight, and Riitho discounts the risk of it being permanently depleted. “The underground water is large," she says. Still, conserving it is crucial to her plan to expand: “I just have this one source of water, so I have to use the water economically."

Riitho is testing a water-saving solution: a drip irrigation line that is irrigating her plot of cabbage, spinach, and potatoes, putting out only enough water to moisten the soil near the plants' roots. A plastic drip line may sound low tech for 2021, but driving one with a minimum of electricity requires some finesse. SunCulture has 15 of its customers testing such drip lines, which are designed for low-pressure activation. The key to such a setup is precise control of the water pressure in the line. “You don't want to put out much pressure beyond the activation point because that energy just gets lost," says Nichols. “But it can't be any lower than the activation point because then no water comes out." The solution is a feedback loop in the pump's motor controller that detects current deviations around the line's activation pressure and stops increasing the flow when the deviations exceed certain limits. It's a fuzzy-logic approach that researchers at the MIT Global Engineering and Research (GEAR) Lab are developing for SunCulture. “If the algorithm is tweaked by the GEAR Lab folks, we can just push it out to all of the devices in the next day or two," says Nichols.

The drip line is working for Riitho, who intends to expand the line to another part of her land. She can do that with no money down by refinancing her solar pump, adding an additional 5 months of payments. “It is worth it," she declares.

The drip lines are a small example of the modern techniques that began sweeping developed-world farms decades ago. Now, SunCulture is expanding into precision agriculture. Gicheru, for example, is one of five customers testing the company's next value-enhancing digital innovation: combining data from soil sensors and hyperlocal weather forecasting to generate agronomic advice. Soil sensors connect to the battery base unit via Bluetooth, and their readings of moisture, temperature, and conductivity—a proxy for pH—are then uploaded to SunCulture via cellular.

Alex Gitau, SunCulture's field engineer in Nanyuki, the closest town to Matanya, says the data will initially be used to advise farmers on irrigation timing and volume. Eventually, he says, smart algorithms will inform fertilizer applications and crop selection. Farmers spend a lot of time and effort tracking down such advice. With the SunCulture agronomy system, “the farmer doesn't need to go to Nanyuki to go from one agronomist to another, or look for an agricultural extension officer to come to his farm," Gitau says. “He can get that help from our device."

For now, SunCulture's expert system is a work in progress. The hardware is ready, thanks to the use of a tiny amplifier designed by Patlun's team to overcome Bluetooth connectivity glitches that the sensors were having. But Nichols says they need more agronomic and mathematics expertise to convert their data into reliable advice. “You need a top-5-percent person, and, as of yet, we've been unsuccessful in recruiting someone to provide that firepower," he says. (Nichols, meanwhile, recently moved on from SunCulture to follow a newfound passion for blockchain-enabled networks.)

If Ibrahim and the SunCulture team have their way, solar irrigation will set off a whole chain of developments that will amplify off-grid solar power's economic impact. SunCulture is one of several firms, for example, testing energy-efficient electric pressure cookers, which are expected to take off in the next year or two, as solar-panel and battery costs continue to fall, boosting the amount of electricity that an off-grid solar system can supply. Other appliances nearing a breakthrough include egg incubators, grain processors, and refrigerators.

Gicheru's wish list for his solar system includes electric fencing against herd-raiding hyenas and remote video surveillance. He says security cameras would provide a sense of safety to women in Matanya, and he'd welcome them to help deter thieves. “Once the tomatoes start to ripen, people will come around here," he says.

This yearning for electric enhancements is attracting competitors, such as Mwezi, an England-based distributor that markets off-grid technology in the agricultural basin around Lake Victoria, in western Kenya. Mwezi recently began test-marketing egg incubators and a 400-watt hammer mill for grinding corn from Nairobi-based Agsol. Mike Sherry, Mwezi's founder and director, says both devices are affordable, thanks to a financing platform from San Francisco–based Angaza, which specializes in pay-as-you-go account management.

Sherry, like SunCulture's principals, sees a proliferation of solar-powered devices having an impact well beyond any immediate productivity gains. For one thing, they help farmers build collateral and a credit history. While Monicah Riitho plans to refinance her solar pump to purchase more drip lines, such refinancing could be used to purchase just about anything—goods, insurance, or education. For that reason, Sherry says, “We're not a solar company. We're a last-mile retailer."

Ibrahim has a similar vision for SunCulture, but he says realizing it will require many more years unless public investment expands. Subsidies could accelerate the uptake of solar irrigation, following the model of rural electrification elsewhere. A 2020 study from Duke University found that countries that successfully electrified during the last half century did so by subsidizing 70 to 100 percent of the cost of rural grid connections (much as the United States did starting in the 1930s).

Kenya's government is upping its support for off-grid solar via a World Bank–financed program that targets 14 counties where 1.2 million households have no access to electricity. The program includes a $40 million investment in stand-alone solar systems and solar water pumps.

Dalberg, the Geneva-based consultancy, endorses even greater support for solar irrigation. Without subsidies, Kenya's solar-pumping market will experience gradual growth, a 2020 Dalberg policy paper projects. But a 9.6-billion-shilling ($90 million) government investment over five years to cover half the installed cost of solar water pumps would nearly triple the pace of installation, amounting to an additional 274,000 solar water pumps by 2025. Small farmers' income would rise by a cumulative 622 billion shillings. When these subsidies are combined with other policy interventions, the proportion of Kenya's arable land under irrigation would rise from 3 percent to as much as 22 percent, while food imports would fall by the end of the decade.

Monicah Riitho's farm is already part of that future. She sells her produce to the small shops and restaurants in town and to neighbors. As she chases off the cow that's pushed through a rotten fence to help itself to some greens, it's clear there's more tasks than time. But Riitho says she has no complaints. Solar irrigation is about being her own boss. “I'm on my own, and I'm happy because I'm working daily for my children. I have no worries."

This article appears in the June 2021 print issue.

Big Plans in Kenya