The field of plasmonics—which exploits the waves of electrons generated when photons strike a metal structure in order to carry out optoelectronic processes—has been building momentum in the research community over the past half decade. This interest is well placed. Plasmonics has made all sorts of interesting things possible, such as confining wavelengths of light to design smaller photonic devices. During that time, a range of two-dimensional materials, including black phosphorus and graphene, has enabled this growing interest. But the granddaddy of nanomaterials—the single-walled carbon nanotube—may still have a role to play in this exploding field.

Researchers at Peking University in China have gone back to single-walled carbon nanotubes (SWNTs) and used them as the active channel materials in the construction of surface plasmon polariton (SPP)-based plasmonic interconnect circuits. (Just as a bit of a primer, the waves of electrons that are generated when photons hit a metal structure are called either surface plasmons when referring to the oscillations in charge alone, or surface plasmon polaritons when referring to both the charge oscillations and the electromagnetic wave.)

These latest plasmonic interconnect circuits, which are described in the journal Science Advances, actually build on research conducted previously by the Peking scientists. In 2014, they developed a dopant-free technique using SWNTs.

The dopant-free technique called for contacts to be used to tune the device polarity, which involves the use of symmetric contacts for a CMOS transistor, i.e. scandium-scandium (Sc-Sc) for N-type transistor and palladium-palladium (Pd-Pd) for P-type transistor. Asymmetric contacts such as Pd-Sc were used for the optoelectronic diode.

“This doping-free technique is much simpler than the doping method used in current semiconductor industry,” said Lin Mao Peng, who was the lead researcher for both the 2014 experiments and this latest research, in an e-mail interview with IEEE Spectrum. “It’s more compatible with plasmonics because you only have to choose different types of metal to realize different functions with the same fabrication technique.”

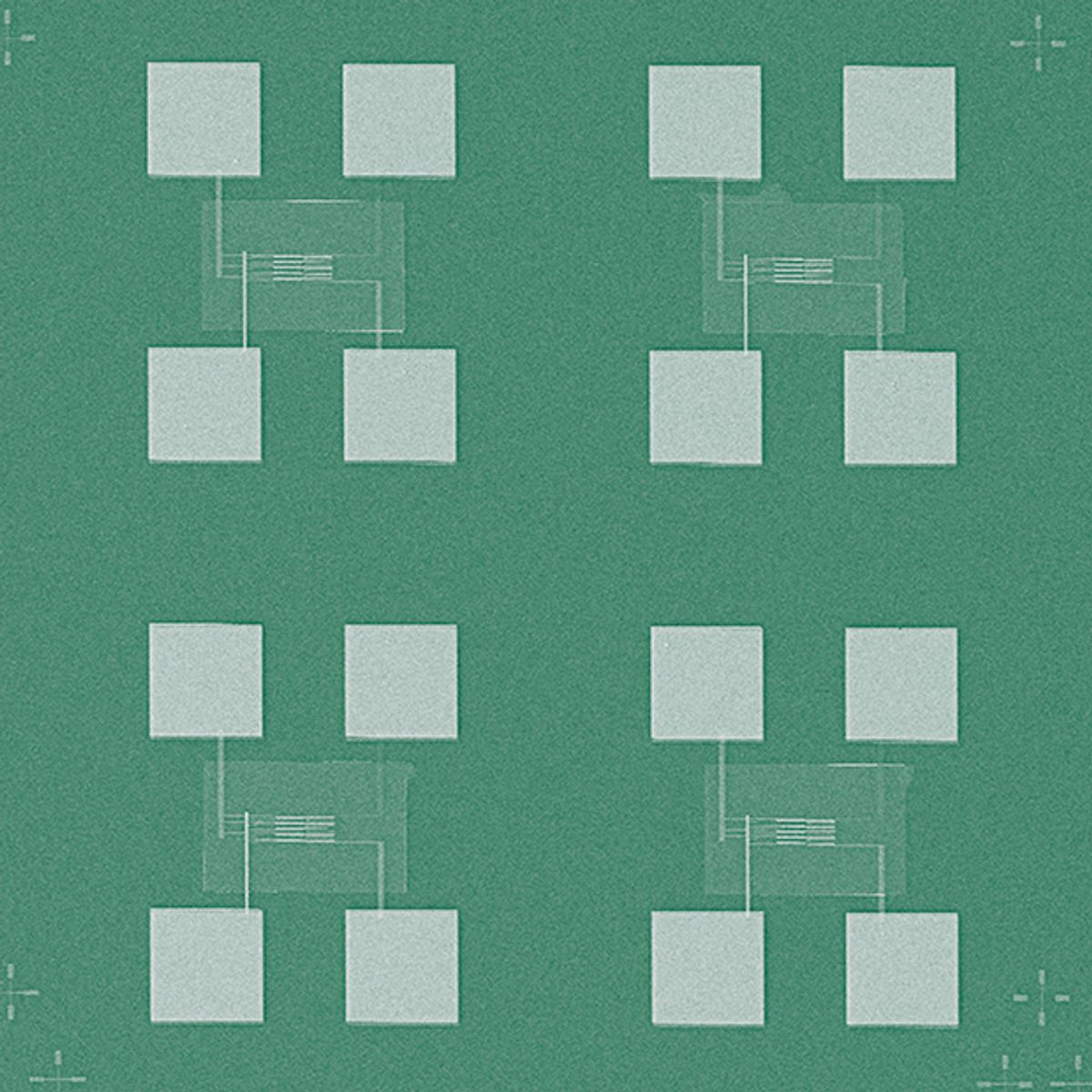

This doping-free technique has made it possible to fabricate complete plasmonic interconnect circuits consisting of a photovoltaic cascading detector, gold-strip waveguides and electrically-driven surface plasmon polariton sources. These could be potentially used as optoelectronic integrated circuits for monolithic optical connections and hybrid optoelectronic logic, according to Peng.

Peng points out that the nature of the doping-free method for fabricating these devices is ohmic or “barrier-free” contact, meaning there exist no Schottky barriers to either the conduction or valence bands of the active channel materials. While the doping-free technique has made the design of their device possible, the SWNTs are critical to their function.

“To date, SWNTs are the only candidate that satisfies the requirements of valence and conduction bands via palladium and scandium at the same time,” said Peng. “Nanowires cannot satisfy this requirement owing to the strong Fermi-pinning effect. Graphene is a zero-bandgap material, which cannot be utilized as an active channel material for constructing transistors or up to digital integrated circuits level.”

In operation, the device functions by electrically exciting the SWNTs, which release their excitation energy to surface plasmon polaritions (SPPs) in the near-field region. Afterwards, these SPPs propagate at the bottom surface of the gold-strip waveguide toward the detector. Finally, the propagating SPPs are directly absorbed and converted into electrical signals by the near-field photovoltaic cascading detector.

The key feature in this process, according to Peng, is that the conduction medium for interconnection is the SPPs from the source to the detector. This enables the construction of plasmonic inteconnect circuits beyond the diffraction limits.

But more materials engineering will be required before this integration scheme will be practical for in commercial applications, according to Peng. This harkens back to the same old bugbears plaguing the carbon nanotube: purity and getting them where you want them.

“The semiconducting purity of the CNTs should be further improved to single chirality level for enhancing the output of the source,” said Peng. “In addition, the CNT morphology should be arranged as parallel arrays with confined pitch to improve the coupling efficiency of the source and the detection efficiency of the detector.”

Now that Peng and his colleagues have successfully constructed a complete plasmonic internconnect circuit at sub-wavelength scale, the next step will be to integrate these plasmonic devices with CNT-based CMOS integrated circuits capable of signal processing.

Dexter Johnson is a contributing editor at IEEE Spectrum, with a focus on nanotechnology.