In novel materials known as topological insulators, electricity or light can flow around corners and defects with virtually no losses. All topological insulators produced so far are comprised of an insulating bulk and perfectly conductive edges. Now scientists have found—at least in theory—that fractal topological insulators could possibly be made up only of edges, with no bulk at all.

Topology is the branch of mathematics that explores what aspects of shapes can survive deformation. For example, an object shaped like a doughnut can get deformed into the shape of a mug, with the doughnut's hole forming the hole in the cup's handle, but it could not get pushed or pulled into a shape that lacked a hole without ripping the item apart.

Employing insights from topology, researchers developed the first electronic topological insulators in 2007. Electrons zipping along the edges or surfaces of these materials strongly resist any disturbances that might hamper their flow, much as a doughnut might resist any change that would remove its hole.

In 2013, scientists created the first photonic topological insulators, in which photons are similarly “topologically protected.” These materials possess regular variations within their structures that cause light to flow within them without scattering or losses, even around corners and imperfections.

All topological insulators created so far have operated in whole numbers of dimensions—specifically, two or three dimensions. In addition, “topological insulators usually have a bulk and an edge. Think about a rectangle — the interior is a bulk and the perimeter is an edge,” says Mordechai Segev, a physicist at the Technion–Israel Institute ofTechnology, in Haifa, Israel. “Topological insulators are insulators in the bulk and perfect conductors on the edge.”

Now Segev and his team have explored fractal topological insulators that operate in fractional dimensions. They found that some fractal structures may theoretically behave as topological insulators even thought they have only edges with no bulk at all.

Segev and colleagues detailed their findings online 21 July in the journal Light: Science & Applications.

"It's all edges, whether the external perimeter or an internal edge," Segev says. "Every single site in this fractal structure is on an edge, whether external or internal. Yet the damn thing still behaves as a topological insulator! This breaks a commonly held belief that topological insulators necessitate a bulk. This one has no bulk at all."

Fractals are never-ending patterns that look the same whether analyzed from near or far, since each part of these geometric figures has a similar character as the whole. Many natural structures, including coastlines, clouds, and networks of rivers and blood vessels, apparently have fractal geometries.

Fractals get their name from how they have fractional dimensions. Familiar shapes such as lines, squares and cubes possess whole numbers of dimensions — a line has one, a square two, and a cube three. One way mathematicians understand dimensions has to do with the number of matching pieces a shape can get divided into. For example, a one-dimensional line can get divided into X^1 identical lines, each of which can get magnified by a factor of X to get a line the size of the original. Similarly, a two-dimensional square can get divided into X^2 identical squares, each of which can get magnified by a factor of X to get a square the size of the original. A three-dimensional cube can get divided into X^3 identical cubes, each of which can get magnified by a factor of X to get a cube the size of the original, and so on.

In contrast, when one divides a fractal shape into identical components, the infinitely complex nature of its boundaries means the relationship between the parts of the fractal and the whole is best described with fractional dimensions, instead of whole numbers of dimensions as with standard geometric shapes.

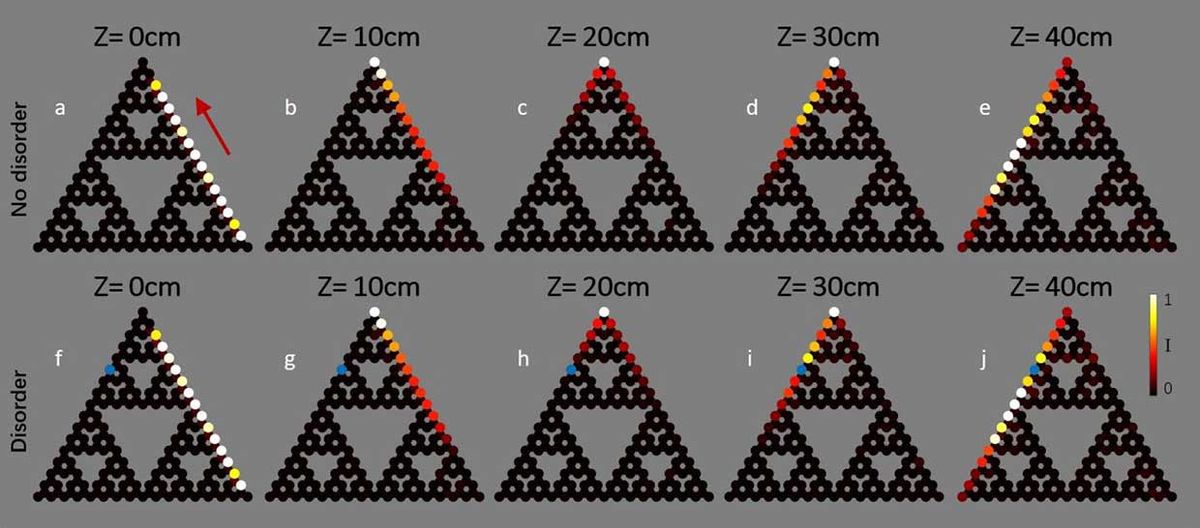

The researchers investigated how light might behave in an array of corkscrew-shaped waveguides. The arrangement of this array mimics the fractal known as the Sierpiński gasket, which has the overall shape of an equilateral triangle divided into smaller identical triangles as well as triangular holes.

The scientists' computer models found light could flow, topologically protected, along the inner or outer edges of such fractal lattices. Moreover, light could flow topologically protected from this fractal topological insulator into a standard photonic topological insulator with a honeycomb lattice, and vice versa, despite the shifts from two dimensions to a fractional dimension.

The fractals displayed topological protection even when the structures were made up mostly of holes, unlike standard topological insulators, the bulk of which are solid. The researchers found similar results with a fractal known as the Sierpiński carpet.

Segev notes it remains uncertain what advantages fractal topological insulators might have over standard topological insulators when it comes to applications. Perhaps the fact that fractal topological insulators possess holes as opposed to solid bulk could make them easier or cheaper to fabricate, or help them fit into places where solid bulk is less convenient, he notes. “To us, this was a profound physical discovery. That's all,” Segev says.

The scientists are now fabricating these fractal lattices in fused silica using direct laser writing.

Charles Q. Choi is a science reporter who contributes regularly to IEEE Spectrum. He has written for Scientific American, The New York Times, Wired, and Science, among others.