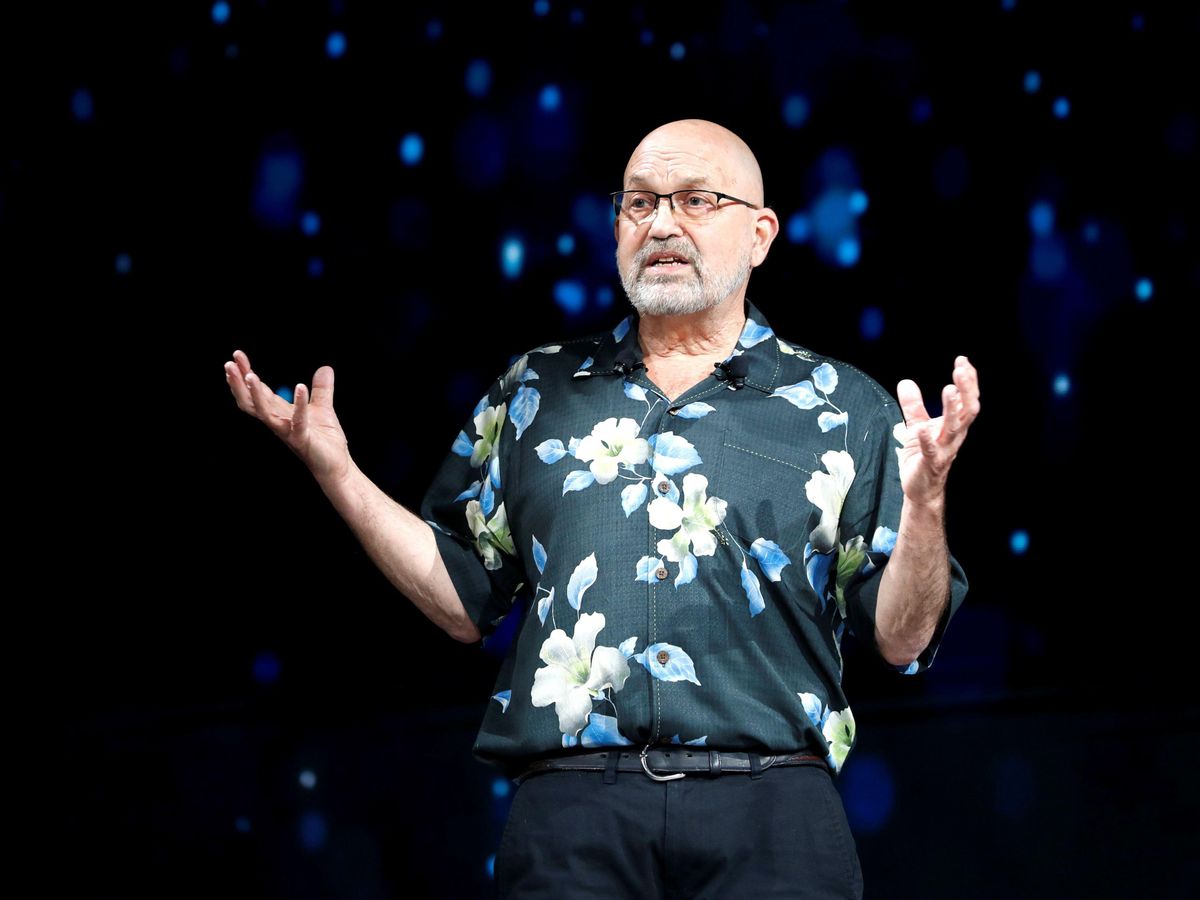

Last week, Hyundai Motor Group and Boston Dynamics announced an initial investment of over US $400 million to launch the new Boston Dynamics AI Institute. The Institute was conceptualized (and will be led) by Marc Raibert, the founder of Boston Dynamics, with the goal of “solving the most important and difficult challenges facing the creation of advanced robots.” That sounds hugely promising, but of course we had questions—namely, what are those challenges, how is this new institute going to solve them, and what are these to-be-created advanced robots actually going to do? And fortunately, IEEE Spectrum was able to speak with Marc Raibert himself to get a better understanding of what the Institute will be all about.

Marc Raibert on:

If we can start by looking back a little bit—what kind of company did you want Boston Dynamics to be when you founded it in 1992?

Marc Raibert: The truth is, at that point, it wasn’t going to be a robotics company at all. It was going to be a modeling and simulation company. I’d been a professor for about 15 years by then and was really well funded (heavily by DARPA [the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency]), but I wasn’t sure that the funding was going to continue. We’d produced some modeling and simulation results that seemed interesting, so I decided to start Boston Dynamics and see what it could be.

It took a while before we got back to robotics. Sony was really the trigger—we’d worked for them quietly for about five years and made a running AIBO which never saw the light of day, and then we worked on their little humanoid QRIO, building tools that made it possible to do choreography. So that was sort of the crossover, applying our modeling and simulation tools to Sony’s robots. And then we decided to write a proposal for BigDog, and the whole company changed almost immediately. It felt great to return to building machines, and I’ve never looked back.

Did you miss academia at all, or do you prefer the approach that you took with Boston Dynamics?

Raibert: Part of the idea for the Institute is to combine the best of the academic world and the best of the industrial lab world. Universities have these very creative, forward-looking people who frequently aren’t bothered by whatever the legacy solutions are. And they’re frequently going for blue sky research. An industrial lab has the kind of teamwork that, in my opinion, is really hard to find in an academic setting, along with schedules and budget discipline and a skilled staff who can be there gaining experience for decades. So when you combine those, I think that’s really a sweet spot. It’s how Boston Dynamics’ research works, and it’s what we’re going to try to do at the Institute.

“If you’re going to try and look over the horizon rather than just advance things incrementally, you have to try wacky stuff.”

How important do you think it is to make robots that are useful and practical?

Raibert: It’s not that we’re not worrying about eventually making things that are useful, but if you’re going to try and look over the horizon rather than just advance things incrementally, you have to try wacky stuff. So that’s part of the plan, to try things that don’t immediately seem practical.

For a while, I felt guilty about building one-legged hopping robots. On the one hand, it was technically interesting and different, but on the other hand, it was really hard to see how they could ever get to the point where they would be useful for anything. But the underpinnings of those one-legged hopping machines, focusing on the dynamics, I think really got Boston Dynamics to where it is today, where they’re making robots that are practical and useful and can do things that we would have never gotten to if we’d kept plodding along the way that other legged robots were at the time. I believe in the necessity of wandering the desert before you can get to a place where you’re making a practical, money-making thing.

We have to remove the pressure to make things more reliable, more manufacturable, and cheaper in the short term. Those are things that are important, but they’re in the way of trying new things. The pitch I made to Hyundai explicitly says that, and proposes funding that extends long enough that we’re not distracted in the short term.

Why is now the right time for this?

Raibert: Boston Dynamics is really starting to be successful doing commercial stuff, and that’s not my long suit. My long suit is to dream, and to do the long-term stuff. For a long time, Boston Dynamics was primarily doing that, and they’re still doing some really exciting long-term work, but I wanted to focus squarely on it.

“I don’t think the lay public understands how stupid robots are compared to people.”

Let’s talk about the four areas that the new Institute plans to focus on. What’s Cognitive AI, and why is it important?

Raibert: The new thing that’s clearly different from what Boston Dynamics is doing, is to make robots smarter, in the sense that they need to be able to look at the world around them and fundamentally understand what they’re seeing and what’s going on. Don’t get me wrong. This is currently science fiction, but I've learned that if you keep working on something like this long enough with enough resources, you may be able to make progress. So, I’d like to make a robot that you can take into a factory, where it watches a person doing a job, and figures out how to do that job itself. Right now, it takes a fleet of programmers even for simple tasks, and every new thing you want your robot to do is a lot of work. This has been clear for years, and I want to find a way to get past that. And I don’t think the lay public understands how stupid robots are compared to people—a person could come into my workshop and I could show them how to do almost any task, and within 15 minutes, they’d be doing it. Robots just aren’t anything like that...yet.

There are a lot of people making progress on problems like these in academia. Are you hoping to bring them into the Institute, or support them directly in academia, or how do you picture this working?

Raibert: We’re in this airplane that hasn’t gotten off the ground yet, and we’re going to try everything. We are going to try to hire academics to come work for us—I have an academic background and so does Al Rizzi, my CTO, and while I had a happy time in academia, this is even better and I think we’ll find at least a few people who feel that way too. But we’re also going to have consultants from academia and industry, and we’ll fund some lab work. And of course we want people’s students, and I’d really like to get people with industrial experience as well.

I think something that happens sometimes in academia is that things stay on the blackboard for too long. We want to make room for as much theorizing as we need, but we also want to convert that into tangible demonstrations. I think the physicality is really important.

I also want to say that while we have defined the research area that we’re going to focus on, they just came out of my head and the heads of a couple of other people here. But, the people that we hire are going to have their own ideas of what we should do and what the way forward is, and we absolutely want to count on that and have that be part of our culture. So, we’re trying to get this thing off the ground and flying with our ideas, but we really want to bring in people with ideas of their own.

The second and third technical areas that you’re planning to focus on are Athletic AI, and Organic Design. Can you tell us about those?

Raibert: Athletic AI is making your body work, through balance, energy conservation, maneuvering around obstacles or adversaries in real time, and even low-level navigation. We think that there’s still a lot of athletic progress to be made. And you know, Boston Dynamics is continuing to work on some very interesting stuff in that area, and I’m still chairman of the board over there and I still love that company, and we’re going to try and find paths that are supportive rather than conflicting. But we also have ideas for making advances in the physicality of the robots that we want to work on at the Institute.

Organic Design means mechanical hardware as well as electronics and computing. There, the idea is that in addition to having engineering teams to support our research, we want to use AI to help develop more futuristic designs. We think optimizing a hardware design can take advantage of a lot of different kinds of information, like simulation-based optimization and learning-based optimization, where there’s a lot of opportunity to do things that have never been done before to make the hardware stronger, lighter, more efficient, and maybe, someday, cheaper.

What do you feel is the right balance of focusing on hardware versus focusing on software for things like Athletic AI and Organic Design?

Raibert: At Boston Dynamics, it was a pretty even balance. We started out as being more controls and software focused, and we had a good hardware group, but it was a little more like university lab hardware. But Boston Dynamics has built up its hardware capability, and I think that’s really important. I think the idea that you’re going to have crummy hardware and have software make up for it might be okay for some midrange products, but if you’re going to keep pushing the boundaries and achieve animal and human levels of athleticism and then exceed them, you want the hardware to be as absolutely great as you can make it, and there’s still a lot of opportunity to move that ahead. But the software can obviously do a huge amount, too. So it’ll be both sides catching up to each other, forever!

“I used to be a guy who would get caught up with some new widget, like a new valve or a new kind of bearing or something. But the system engineering is vastly more important.”

Really, it’s a holistic thing, and when I talk about Organic Design, I mean taking the software and the hardware into account at the same time—having one eye on the physics and what the controller has to do to deal with that, and one eye on the hardware which also has to deal with the physics, and growing those together. It’s system engineering. I used to be a guy who would get caught up with some new widget, like a new valve or a new kind of bearing or something. But the system engineering is vastly more important, and there’s so much optimization and improvement that can be done with the right combination of things, even if each individual component is a little less than perfect.

You’ve put so much work into Atlas at Boston Dynamics—will you be bringing that program with you to the Institute?

Raibert: No, we’re not going to. Boston Dynamics has a strong team working on Atlas, and wants to maintain their R&D ability, and so Boston Dynamics will continue with that. At some point the Institute may buy some Atlas robots and do some work with them.

The final area that the Institute will focus on is Ethics and Policy. Why does that deserve equal importance to the technical focus areas?

Raibert: If you look at even just the headlines about Boston Dynamics, there’s a lot of emotion there, and a lot of concern. I think it only makes sense if we’re going to be leaders in this area that we do some disciplined thinking about ethics, bringing in some outside people who perhaps aren’t as enthusiastic about the kinds of things that we’re doing as we are. But also, I think there’s a very positive story to the ethics of what we do, and we’ll try to articulate that as best we can.

There are four topics that always come to mind for me. One is the use of robots by the military, one is robots taking jobs, and one is killer robots (or robots that are intended to harm people without human-in-the-loop regulation), and one is the idea that robots will somehow take over the world against the will of human beings. I think the last two are where you get the least grounding in what’s really happening, and the others are works in progress. The military topic is a very complex thing, and with the jobs topic, yes, some people’s jobs will be done by robots. Other jobs that don’t yet exist will be created by robots. And robots will help people’s existing jobs become safer and easier. I hope we’re going to be open about all of these things—I’m not embarrassed about my opinions, and I think if we can have an open conversation, it’ll be good.

“I think the Institute needs to be different and more open and more available, and certainly the best talent these days wants to be able to publish the big ideas they’re working on and we’re going to accommodate that.”

How open will the Institute be with the research that it’s doing?

Raibert: We’ll be more open than Boston Dynamics has been with respect to working with universities and with publishing. I don’t blame anyone but myself for that. I wasn’t much of a collaborator in the early days of Boston Dynamics and didn’t really want to show the public too much too early. I think the Institute needs to be different and more open and more available, and certainly the best talent these days wants to be able to publish the big ideas they’re working on and we’re going to accommodate that.

You mention caring for people and helping people live better lives as things that you hope robots will be able to do. What’s the path toward making robots that are dynamic and capable but also safe for humans to be around?

Raibert: I’m of two minds. The very athletic robots are the hardest to make safe, but I think that there are going to be a lot of useful things that those robots will do where they aren’t safe enough for people to be around. We should keep working on those things. But on the other hand, having a robot that isn’t dynamic at all is really hard to make useful. It’s a tough problem, and I’m sure there are paths that we haven’t thought of yet to make things safer. So I don’t know what the answers are, but we’re going to see what we can do.

With this long-term vision that you have for the Institute, how will you measure success? What will make you feel like the Institute did what it was supposed to do?

Raibert: That’s a good question. One indication of success will be that good people want to join us and work there. So far, the people I have talked to have been very interested, so I’m optimistic. Two other important measures in the past have been: Do our funders keep funding us, and how many views do we get on YouTube! YouTube really changed everything—if my career had been based on writing papers with lots of equations and plots, I don’t think anybody would have ever cared. But the fact that we could visualize what we were thinking, and where we thought we could go, had a big impact on the work that we did.

Can you elaborate a little bit on why making YouTube videos is so important?

Raibert: The very first BigDog video, we put on our website but not on YouTube. We didn’t know about YouTube at that time, and someone else posted it on YouTube instead. And then my partner Rob [Playter, now the CEO of Boston Dynamics] and I went to DARPA’s 50th anniversary dinner [in 2008]. We were just contractors, but we decided to introduce ourselves to Tony Tether, the head of DARPA. We said, “We’re from the company that makes BigDog,” and immediately he says, “BigDog, three and a half million YouTube views!” And we realized, oh, this matters!

As an academic, I had totally resisted the media, and I thought it was unseemly to appeal to the media. But once Boston Dynamics was commercial, and we wanted to sell projects and sell machines, we found out the value of having people know who we were. YouTube helped Boston Dynamics to be widely known around the world, without any marketing budget. And it’s fun to get recognition for your work!

To come back to my previous question: What then do you think will make Hyundai feel as though the Institute is successful, so that they keep funding you?

Raibert: Our top-level mission is to help Hyundai embrace these new technological areas. I think they made a bold move by buying Boston Dynamics to help with that, and they’re also working on a new Global Software Center. They’re really thinking big about these long-term technologies, even beyond automobiles as mobility in general goes through a transition. As the Institute gets a little further along, I think some of our work will get done jointly with Hyundai, and some of our people will help Hyundai with things they want to develop. Urban air mobility might be an area where there’s some crossover, for example.

“I sincerely believe that having a different paradigm, where we don’t focus on a product that we’re going to launch in a couple of years with all the incremental work it takes to make that happen, is really going to be an asset for the field.”

How far will this go? Will the Institute be doing entirely basic research, or will you also be working toward productization?

Raibert: My hope is that we can follow in the footsteps of the Broad Institute, the Whitehead Institute, the Max Planck Institute, and even the old Bell Labs. But I’m afraid of the impact of focusing on practical applications. Getting Spot to go all the way through to adoption in a routine utility environment, for example, is a lot of work, and I don’t want the Institute to get sidetracked too much. We’re all for other groups, like Boston Dynamics or other Hyundai organizations or maybe outside organizations, taking our technology and doing something practical. We may do some spinouts, where people at the Institute create a new company and we help them along. But I would rather that be a separate thing. I sincerely believe that having a different paradigm, where we don’t focus on a product that we’re going to launch in a couple of years with all the incremental work it takes to make that happen, is really going to be an asset for the field.

Does this feel more like the end of something for you or the beginning of something?

Raibert: Totally the beginning! I’ve been working on setting this up for long enough that there’s no tears about the transition. Boston Dynamics is firing on all cylinders, I get to be on the board, I still have a badge so I can go in if I want, it’s great. And the Institute is off to a great start with remarkable support from Hyundai. I’m at the age where I should be retiring, but I’m not going to—this is better!

Evan Ackerman is a senior editor at IEEE Spectrum. Since 2007, he has written over 6,000 articles on robotics and technology. He has a degree in Martian geology and is excellent at playing bagpipes.