Just a few years ago, Lockheed Martin was working to build a pilot plant to demonstrate a renewable energy technology called ocean thermal energy conversion (OTEC) near the Hawaiian island of Oahu. The company wanted to get funding from the U.S. Navy for the pioneering project and to cable the electricity it produced straight to the naval base at Pearl Harbor.

Now Lockheed is designing that 10-megawatt pilot plant—but not in American waters. Instead, the facility will be off the coast of southern China, and Lockheed’s customer is a private Chinese company that develops resorts and luxury housing.

Over the years Lockheed has approached various potential partners, says Rob Varley, the company’s OTEC project manager. Building an offshore energy station at commercial scale is an expensive proposition, particularly when it’s the first time the technology is being tried out. Lockheed won’t release the cost of the project, but outside experts estimate that a 10-MW facility would cost roughly US $300 million to $500 million. However, experts say that a full-scale 100-MW plant would be more competitive at just $1.2 billion.

“The biggest challenge has been to get the gold and start the project,” says Varley, but in terms of engineering, he says, “I don’t see any showstoppers at this point.”

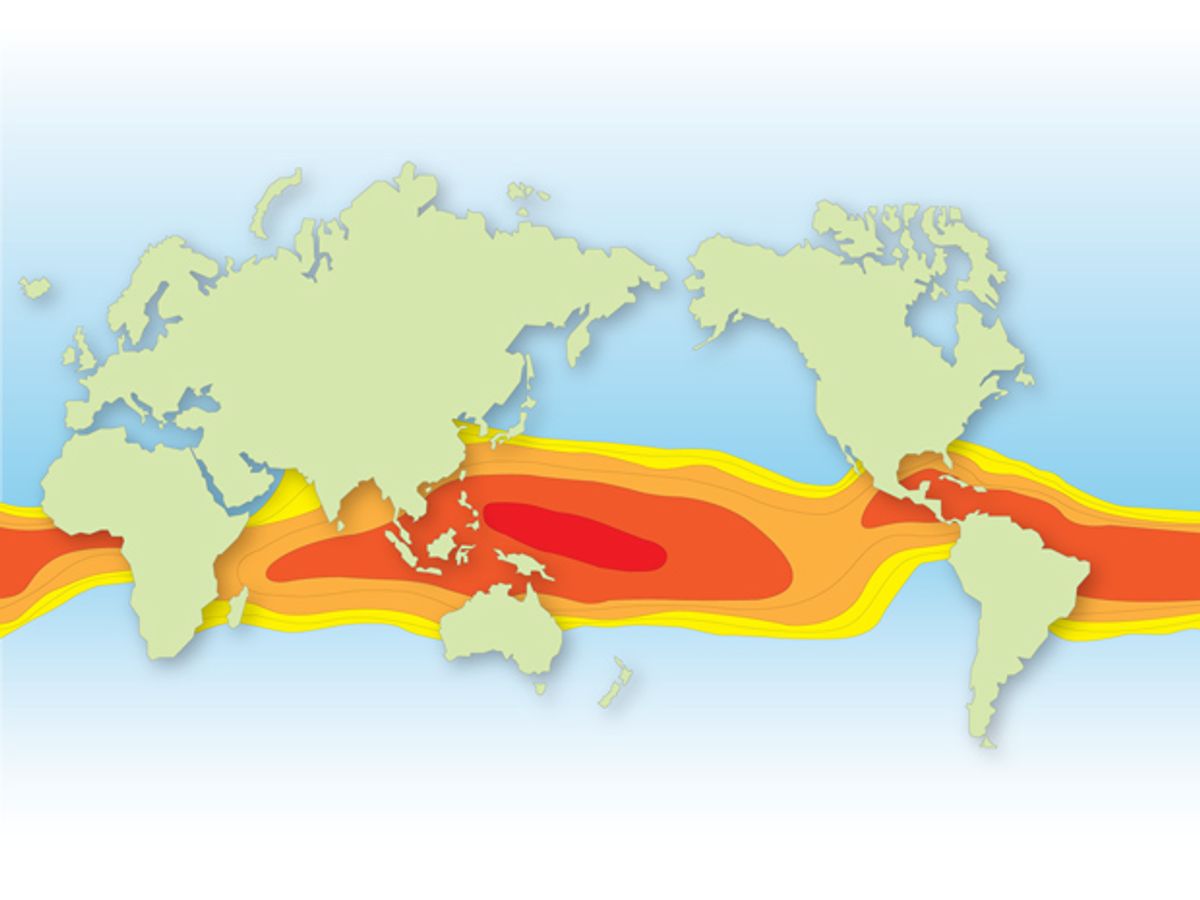

That’s not surprising, since the company has been working on OTEC since the 1970s, and the technology hasn’t changed drastically since then. OTEC systems make use of the temperature differential in tropical areas between warm surface water and cold deep water. In most systems, ammonia, which has a very low boiling point, passes through a heat exchanger containing the warm water. The ammonia is vaporized and used to turn a turbine, and then it’s cycled past the cold water to recondense. This is a renewable energy technology with the rare capacity to supply base-load power, as water temperatures are fairly stable.

The ammonia passes through a closed loop, while the water comes and goes through massive pipes. The project in China may pump cold water up from a depth of about 1000 meters, using a pipe that’s 4 meters across. Varley says that some of the infrastructure can be borrowed from the offshore drilling industry: “We showed them our requirements for the platform, and they yawned and said, ‘Is that all you got?’ ” he says. “But then we showed them the pipe.” Attaching the massive pipe to a relatively small floating platform creates unusual stresses, Varley says. Lockheed also had to find materials for the pipes and the heat exchangers that could withstand the harsh marine environment.

Lockheed’s client is Reignwood Group, a Chinese company whose diverse portfolio includes resort and housing developments. According to a company press release, Reignwood Group wants the 10-MW plant to supply all the power for a large-scale environmentally sound resort community that the company will build in southern China. A Reignwood spokesperson did not respond to requests for more details by press time. A Lockheed spokesperson says the companies are currently working on site selection and that they’ll start designing a facility this year to suit the specific conditions at that site.

The China project isn’t the only OTEC project going ahead. Baltimore-based OTEC International is negotiating the terms of a 1-MW demonstration plant in Hawaii, and the company is planning much bigger facilities in Hawaii and the Caribbean. Both OTEC International and Lockheed Martin see their current plans as steps toward a much more ambitious goal: utility-scale OTEC plants. “Going from a PowerPoint to a 100-MW would be too big a leap,” says Lockheed’s Varley.

OTEC advocates have been trying to build megawatt-scale facilities for decades, but several ambitious projects have failed to materialize. So why should it be different this decade? Eileen O’Rourke, president of OTEC International, says there’s a convergence of favorable conditions. “Island jurisdictions like Hawaii have very high energy prices and limited alternatives for base-load power, and OTEC fits with their desire to be energy independent and green,” she says. Add in mature technology from the offshore oil industry, she says, and “we just think the time is right for OTEC.”