It's a problem as old as radio: Radios cannot send and receive signals at the same time on the same frequency. Or to be more accurate, whenever they do, any signals they receive are drowned out by the strength of their transmissions.

Being able to send and receive signals simultaneously—a technique called full duplex—would make for far more efficient use of our wireless spectrum, and make radio interference less of a headache. As it stands, wireless communications generally rely on frequency- and time-division duplexing techniques, which separate the send and receive signals based on either the frequency used or when they occur, respectively, to avoid interference.

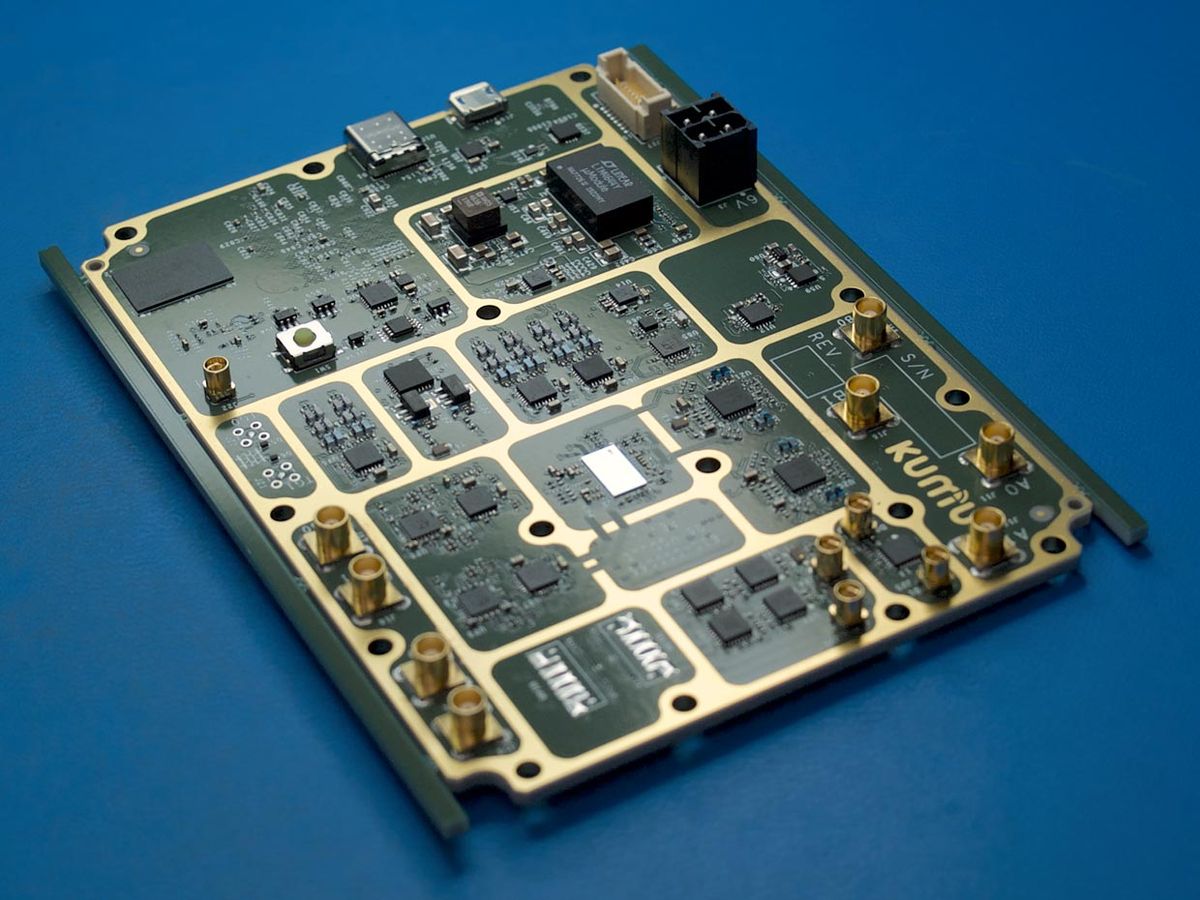

Kumu Networks, based in Sunnyvale, Calif., is now selling an analog self-interference canceller that the company says can be easily installed in most any wireless system. The device is a plug-and-play component that cancels out the noise of a transmitter so that a radio can hear much quieter incoming signals. It's not true full duplex, but it tackles one of radio's biggest problems: Transmitted signals are much more powerful than received signals.

“A transmitter signal is almost a trillion times more powerful than a receiver signal," says Harish Krishnaswamy, an associate professor of electrical engineering at Columbia University, in New York City. That makes it extra hard to filter out the noise, he adds.

Krishnaswamy says that in order to cancel signals with precision, you have to do it in steps. One step might involve performing some cancellation within the antenna itself. More cancellation techniques can be developed in chips and in digital layers.

While it may be theoretically possible, Krishnaswamy notes that reliably reaching that mark has proven difficult, even for engineers in the lab. Out in the world, a radio's environment is constantly changing. How a radio hears reflections and echoes of its own transmissions changes as well, and so cancellers must adapt to precisely filter out extraneous signals.

Kumu's K6 Canceller Co-Site Interference Mitigation Module (the new canceller's official name) is strictly an analog approach. Joel Brand, the vice president of product management at Kumu, says the module can achieve 50 decibels of cancellation. Put in terms of a power ratio, that means it cancels the transmitted signal by a factor of 100,000. That's still a far cry from what would be required to fully cancel the transmitted signal, but it's enough to help a radio hear signals more easily while transmitting.

Kumu's module cancels a radio's own transmissions by using analog components tuned to emit signals that are the inverse of the transmitted signals. The signal inversion allows the module to cancel out the transmitted signal and ensure that other signals the radio is listening for make it through.

Despite its limitations, Brand says there's plenty of interest in a canceller of this caliber. One example he gives is an application in defense. Radio jammers are common tools, but with self-interference cancellation, they can ignore their own jamming signal to continue listening for other radios that are trying to broadcast. Another area where Brand says Kumu's technology has received some interest is in aerospace, with one customer launching modules into space on satellites.

Kumu also develops digital cancellation techniques that can work in tandem with analog gear like its K6 canceller. However, according to Brand, digital cancellations tend to be highly bespoke. Performing them often means “cleaning" the signal after the radio has received it, which requires a deep knowledge of the radio systems involved.

Analog cancellation simply requires tuning the components to filter out the transmitted signal. And because of that simplicity, Kumu's module may well find its place in noisy wireless environments such as the home—where digital assistants like Alexa and smart home devices have already moved in.

This article appears in the January 2020 print issue as “Helping Radios Hear Themselves."

Michael Koziol is an associate editor at IEEE Spectrum where he covers everything telecommunications. He graduated from Seattle University with bachelor's degrees in English and physics, and earned his master's degree in science journalism from New York University.