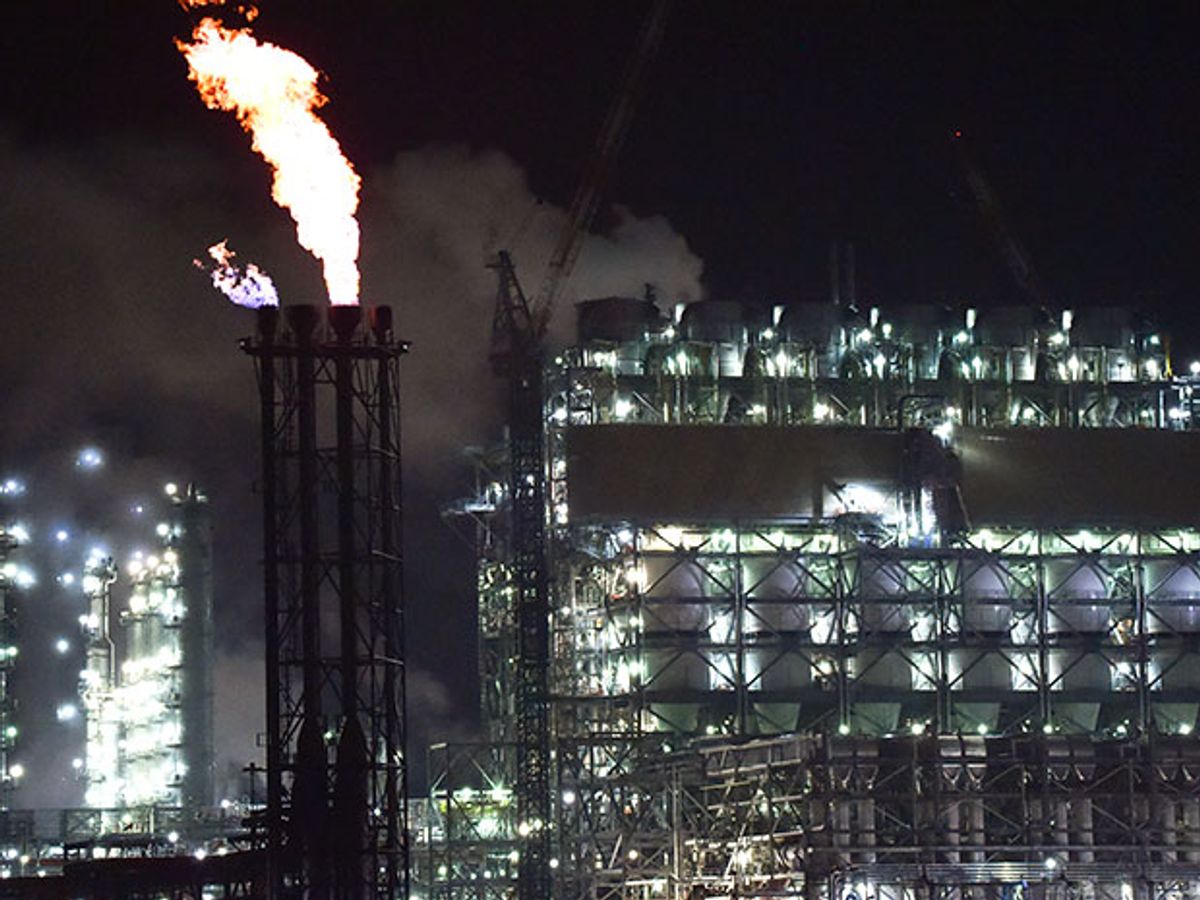

Politicians who talk about the future of “clean coal” as part of the U.S. energy mix need look no farther than the Kemper County Energy Facility in Mississippi to see both the promise and the peril that the technology has to offer.

Kemper is years behind schedule and billions of dollars over the $2.2-billion cost estimate given in 2010 when construction began. And a recent financial analysis paints a dim picture of the plant’s potential for profit.

A decade ago, integrated gasification combined cycle (IGCC) was heralded as the enabler of a continued and even expanded use of coal for electric power generation. The process starts by turning coal into synthesis gas, a combination of hydrogen and carbon monoxide. The syn gas can then be cleaned of impurities, and burned to drive a turbine. Excess heat goes to power steam turbine. Dozens of U.S. projects were proposed. Equipment manufacturers and engineering firms alike focused resources to developing the technology.

Southern Company, whose utility business units operate 44,000 megawatts of installed capacity and generate electricity for 9 million customers across the southern United States, saw an opportunity for IGCC at a location in Kemper County, Miss.

In many ways, a better site for IGCC could scarcely be found. Kemper is close to an estimated 4 billion metric tons of mineable Mississippi lignite, a low-rank coal with high moisture and ash content. Southern owns the lignite fields and saw a way via IGCC to use that coal for power generation. What’s more, Kemper is close to mature oil fields, which became candidates for enhanced oil recovery (EOR)—the use of carbon dioxide captured from the power plant’s coal gasification process to push out the oil.

The clean coal opportunity extended beyond Kemper County and Southern Co. Low-rank coals make up roughly half of the proven coal reserves in the United States and worldwide. Southern, along with KBR and in conjunction with the U.S. Energy Department, developed its own version of IGCC called Transport Integrated Gasification (TRIG). That technology was developed to work with lower-rank coals and presented an opportunity to market domestically and even export the technology.

The Kemper County IGCC Project is a scale-up of a test plant that was already in operation in Alabama. The combined cycle portion of Kemper County has worked well and has been generating electricity since August 2014 with conventional natural gas.

It’s the gasification part of the plant that is proving problematic.

For one thing, the company found that many of the original design specs needed changes, delaying the project and boosting its cost. One design flaw miscalculated pipe thickness, length, quantity, and metallurgy. After these changes were made, additional changes needed to be done to support structures.

For another thing, integrated gasification is something akin to a chemistry set that has been bolted onto a conventional power plant’s front end. IGCC technology is intended not only to produce syngas but also to create marketable byproducts from the gasification process, such as carbon dioxide. The captured carbon dioxide from Kemper was earmarked to help stimulate production at nearby oil fields through EOR.

On paper, at least, IGCC offers an elegant approach to use coal for electric power generation, create cleaner burning synthetic gas, capture and reuse carbon dioxide, and manufacture chemical byproducts for sale. In practice, however, Kemper County’s technology is proving to be troublesome, expensive, and potentially uneconomic to run.

In mid-February, Mississippi Power—the Southern Co. utility that is hosting the project—extended the expected in-service date of Kemper County until mid-March, the latest in a series of rescheduled dates.

The utility said in a statement that while integrated operation of the facility’s gasifiers and combustion turbines has “continued for periods” since late January, the schedule adjustment is needed because of “issues experienced with the ash removal system in one of the gasifiers.”

In particular, the plant has had a reoccurring issue in operating both of its gasifiers reliably over an extended period without forming “clinkers” — ash fused to the gasifier walls. Neither gasifier has operated for longer than about six weeks without clinkers occurring. These chunks of ash are enough to impact the plant’s operating efficiency and bring the facility down for maintenance.

The issues don’t end there. A confidential report [PDF] by URS, made public by in early February the Mississippi Public Service Commission, outlined seven “key technical milestones” in addition to the clinkers that it said had yet to be achieved.

Most of the milestones focused on the gasification technology and the plant’s ability to deliver byproducts (including carbon dioxide for oil recovery) that met environmental specs.

Engineering challenges aside, a separate report called into question the plant’s overall economic viability. In particular, long-term natural gas price forecasts now suggest that the Kemper IGCC may not be competitive when compared to natural gas combined cycle units at the nearby Plant Sweatt site.

In a 19 February earnings conference call, Thomas Fanning, chairman, president and CEO of Southern, said: “When we had this plant certificated (in 2010), we all thought that gas prices were going to be double digits.” By 2016, however, that assessment had changed, resulting in a “reduction of gas price forecasts of 25 to 30 percent.”

Hydraulic fracturing largely can be thanked for the change in fortune. Indeed, as far back as 2011 natural gas prices nationally were low enough to economically displace coal-fired generating units across multiple states.

Coal from parts of the Appalachian and Illinois basins were displaced first as natural gas prices fell and the fuel’s nagging price volatility eased. Among the last to be impacted would be inexpensive, low-rank coals that required little handling to move from the mine mouth to the power plant. Just such a scenario began to hit the Kemper IGCC in late 2016.

“We know that gas forecasts have changed a lot over time,” Fanning said on the analyst call. “And with respect to whether we should recover it or not, I don’t think—I mean as a matter of fairness, I cannot imagine that the company is going to be held accountable for changing gas price forecasts.”

What Fanning was alluding to was the fact that state officials who oversee Mississippi Power ultimately will decide whether or not the Kemper IGCC plant is “used and useful” and how the company can account for and recover the expenses related to its construction.

Regulators already have capped the amount that Mississippi Power customers must pay at just under $3 billion. But another $4 billion need to be accounted for and allocated through regulatory hearings that are expected to start once Kemper County enters service.

As for the upcoming regulatory process, Fanning said: “We certainly have taken our lumps, but we have delivered what was certificated back in 2010.” He expressed confidence that the Kemper IGCC would deliver what was required when IGCC technology was seen as offering an opportunity to develop clean coal for electric power generation.

“Certainly there’s a lot of different ways the regulatory process could unfold from there,” Fanning said. “That’s our starting point.”

Contributing Editor David Wagman has been covering energy issues for three decades, focusing on all forms of electric power generation, regulation, and business models. He is particularly interested in the ongoing electrification of advanced economies and the effects that distributed generating resources could have on efforts to decarbonize national grids. Wagman, who is based in Colorado, is currently editorial director for IEEE Engineering 360, a search engine and information resource for the engineering, industrial, and technical communities.