Please note theadjective above: This article is not about the perennial economic dream of never-ending growth but about indefinite or, more accurately, indeterminate growth, the kind that doesn’t end at a certain date but rather continues for as long as an organism lives.

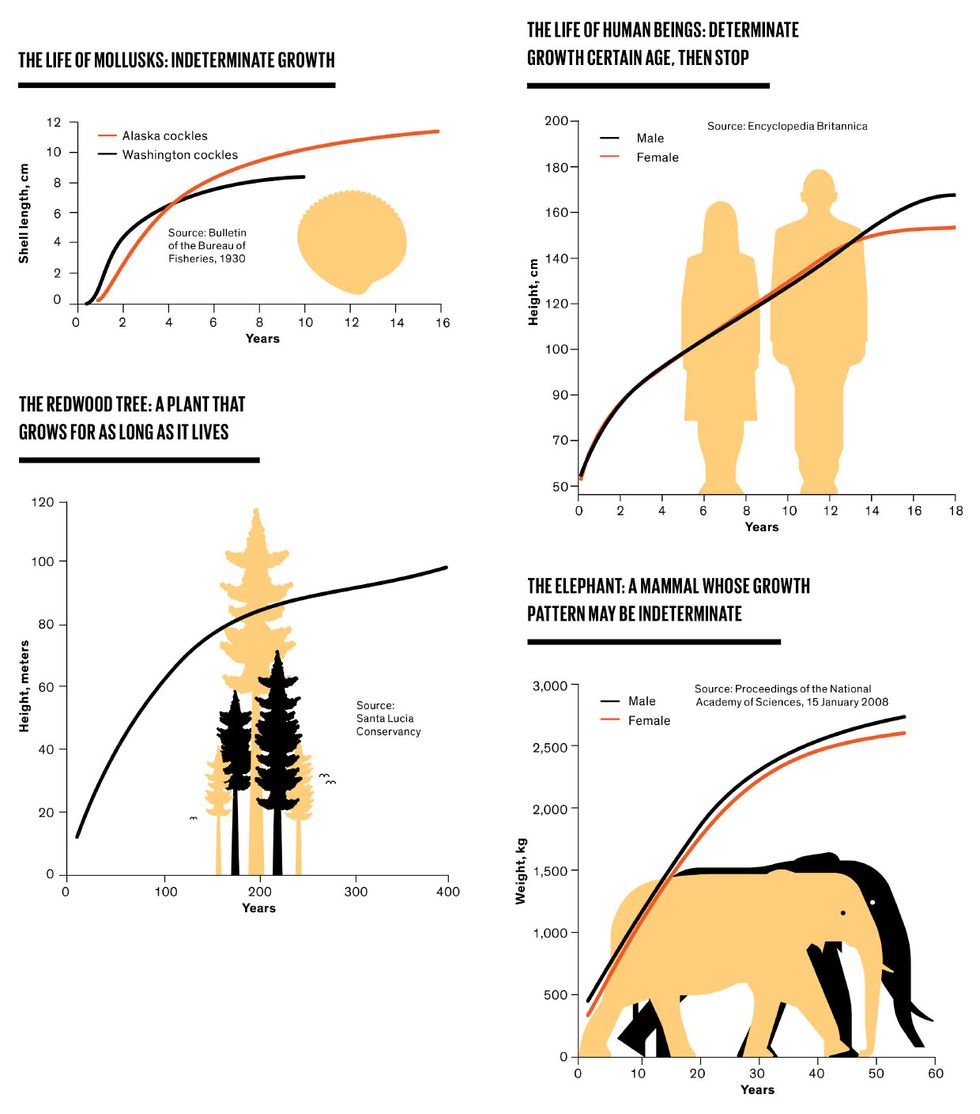

Most organisms stop growing once they reach their mature form. In human beings the final growth spurt starts at puberty, which among boys is at about 12 years old, and stops at around 16. In contrast, some plant and animal species continue to grow until some external cause intervenes to injure or kill them.

For trees this end comes mostly because of metabolic and physical impacts (such as prolonged drought, fire, and hurricane winds) and because of infestation by viruses, bacteria, and insects. For animals, it is most often because of injuries that prevent them from obtaining sufficient energy, and because of accidental death and predation.

Indeterminate growth is common among cold-blooded species, from tiny insects to large lobsters. One of the most common, and most unwelcome, indeterminate growers is the silverfish, a small wingless insect with a fishlike body and two long antennae, which lurks in many basements and in some kitchens and showers. Many insects go through a relatively small number of molts during their lifetime—for example, monarch butterfly caterpillars go through five—but silverfish continue to molt after reaching maturity, some amassing more than 50 molts in a lifetime.

Americans meet most of the indeterminately growing organisms raw or cooked on their dinner plates. These include not only bivalve mollusks (oysters, clams, and mussels), crustaceans (crayfish, shrimp, crabs, and lobsters), but also some long-lived fish species from cold waters (including perch, salmon, and trout). Lobsters off southwestern Nova Scotia become mature when their average weight is 0.7 kilogram. Commercial lobster categories called selects and jumbos weigh, respectively, 0.9 to 1.1 kg and more than 1.4 kg. And old individuals are as impressive as they are rare: One 20.14-kg specimen was caught in Nova Scotia waters in 1977.

For Some Creatures, To Live is To Grow

Many organisms continue to grow throughout their lives, in some cases never even showing the clear onset of senescence. Instead they grow indefinitely, until at last something comes along to kill them.

Indeterminate growth remains disputed among reptiles and mammals. Some argue that it is found in the males of certain mammalian species—elephants, both African and Asian; American bison; and some kangaroo and deer species. The average African male elephant stands 3 meters tall at the shoulders and weighs more than 5.5 metric tons; the largest documented individual, an Angolan male (on display since 1959 at the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History, in Washington, D.C.) was 4 meters tall and weighed nearly 10 metric tons.

But the world’s largest trees provide the most impressive examples of indeterminate growth. Researchers studying the two tallest species—the Australian swamp, or stringy, gum (Eucalyptus regnans) and the coast, or California, redwood (Sequoia sempervirens)—found that their wood, both in the main stem as well as in the entire crown, was still accumulating even in the largest and oldest specimens. Growth ceased only when something came and killed the trees, most commonly fire or fungal attack.

Of course, there is no indeterminate growth for human beings (see “Life-Span and Life Expectancy,” IEEE Spectrum, May 2019), but there is no shortage of human creations that display indeterminate growth.

Libraries and companies are perhaps the best examples. After it was burned by the British in 1814, the Library of Congress was renewed by the purchase of Thomas Jefferson’s books, then suffered another big fire in 1851; it has been growing ever since, now with more than 16 million books and many other items. Most companies do not survive even for three generations, but those family businesses that eventually joined in 1917 to form Kikkoman had been around since 1603, and Japan’s premier maker of soy sauce is still growing, with its stock value up nearly eight times since the year 2000. Cities furnish another obvious example, although very few have seen uninterrupted growth over centuries: Rome may be eternal, but after its decline, it didn’t surpass its imperial size until the 1930s!

Vaclav Smil writes Numbers Don’t Lie, IEEE Spectrum's column devoted to the quantitative analysis of the material world. Smil does interdisciplinary research focused primarily on energy, technical innovation, environmental and population change, food and nutrition, and on historical aspects of these developments. He has published 40 books and nearly 500 papers on these topics. He is a distinguished professor emeritus at the University of Manitoba and a Fellow of the Royal Society of Canada (Science Academy). In 2010 he was named by Foreign Policy as one of the top 100 global thinkers, in 2013 he was appointed as a Member of the Order of Canada, and in 2015 he received an OPEC Award for research on energy. He has also worked as a consultant for many U.S., EU and international institutions, has been an invited speaker in more than 400 conferences and workshops and has lectured at many universities in North America, Europe, and Asia (particularly in Japan).