When a company monopolizes an industry, as the American Telephone and Telegraph Co. did with telecommunications in the United States for much of the 20th century, there’s little incentive for flashy design. Engineers at Bell Telephone Laboratories designed phones that were functional and durable, and Western Electric Co. manufactured the phones and supplied them to the local operating companies of the Bell System.

What wouldn’t have been obvious to the average user was the innovation that went into even the blandest looking phone. In 1927, for example, Bell Labs researchers took thousands of head measurements of men and women of different races in order to optimize the design of the telephone handset. The new data were used to establish the ideal length of the handset, the angles of the handset’s earpiece and microphone, and the distance between the handset and the user’s face.

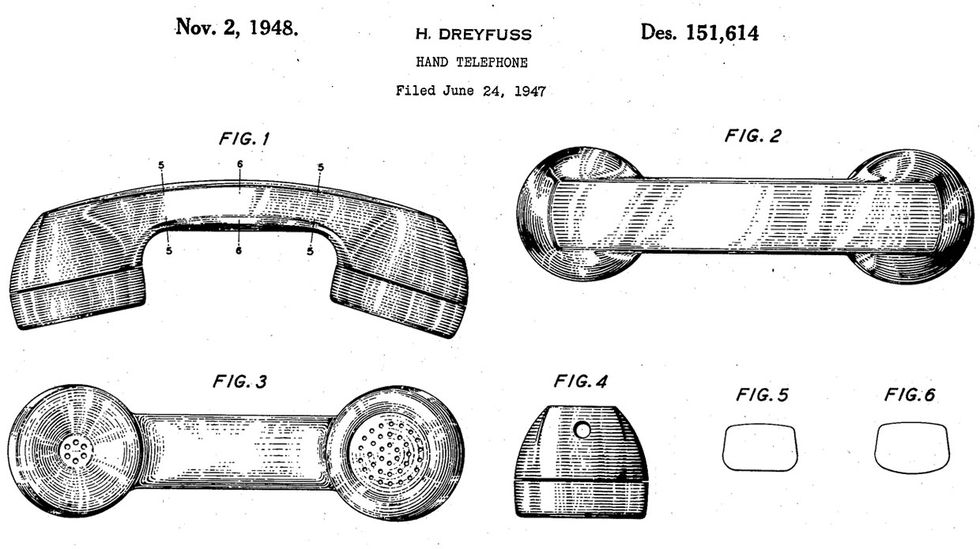

The eventual result became known as the G-type handset, which was patented in 1948 [PDF] by Henry Dreyfuss, the head of a leading industrial design firm that created iconic product designs not just for AT&T, but also for Honeywell, John Deere, and the New York Central Railroad. The company began consulting with the Bell System in 1930 and over the course of several decades collaborated on many models of phones.

The key design element of the G-type handset was that it had a rectangular cross-section. Unlike the triangular cross-section of previous handsets, the G-type could lay flat on a work surface, which made repairs easier. It also made it possible for a user to “shoulder” the phone comfortably in order to go hands-free.

The G-type handset was incorporated into the basic black 500 desk phone, also designed by the Dreyfuss firm and unveiled by AT&T in 1949. The 500 incorporated the best features from several other models, including a handhold cavity beneath the cradle and the relocation of the numbers and letters to outside the finger wheel, which made them easier to see. A decade later, a poll of leading industrial designers ranked the 500 as one of the 10 “best designed products of modern times.”

AT&T was not resting on its laurels. Its next design triumph was already in the works. In 1959, the Princess telephone burst onto the scene in a delicious palette that included rose pink, aqua, and turquoise. A distinct departure from the blocky 500, the Princess was AT&T’s first phone that prioritized fashion over function.

The Princess’s motto summed up its finest qualities: “It’s little. It’s lovely. It lights.” The phone had an oval footprint, and it stood 2 inches shorter than the 500. At just 42 ounces (1.2 kilograms), it also weighed less. Despite its streamlined exterior, the Princess relied on all the same components as the 500, including the G-type handset, which made it economical to manufacture.

A press release announcing the Princess’s debut noted that the phone’s smaller footprint made it perfect for a bedside nightstand, freeing up valuable real estate for the “alarm clock, ash tray, lamp, and facial tissues.” Initially, the small size also meant that there was no room for an internal ringer. A separate ringer could be leased. A few years later, as components continued to shrink, an internal ringer became standard.

Perhaps the coolest feature of the Princess was the night-light on the number plate. When the handset was on the hook, it emitted a dim glow, which grew bright when the handset was picked up.

Back then, AT&T customers didn’t own their own phones but rather leased them for a monthly fee. The basic black 500 was included in your monthly phone bill, but you paid extra for a Princess. You might also need to have an extension line and wall jack installed in whatever room you planned to use it—because of course the Princess predated the first commercial cordless phones by a couple of decades.

From the start, the Princess was designed to appeal to women—the “homemaker with an eye to the niceties of interior décor,” as one press release put it. Internal marketing documents, held at the AT&T Archives and History Center in San Antonio, Texas, suggested that most women wanted to either be a princess or have a princess for a daughter. AT&T also promoted the phone to women-focused businesses, including beauty salons, gift shops, dress shops, jewelry stores, florists, and interior decorating firms.

The in-store promotional kit contained a life-size cardboard cutout of a princess holding the Princess. Princess phones in every color were displayed on velvet pillows. Female sales staff wore tiaras, with additional tiaras on hand to give to customers’ daughters.

It’s hard to imagine the phone being called anything else, but “Princess” was just one of several hundred names that were considered. (Before the Princess, the Bell System had never done research on what to name a phone.) In 1956, the marketing department began conducting an exploratory study with potential customers, who gave their opinions on over 300 product names. In addition to the winning Princess, the other finalists were the Slimphone, Slenderphone, Fashion Phone, Companion, and Petite Phone.

Slimphone and Slenderphone were deemed more appropriate for a wall phone. Fashion Phone got dinged because it suggested that the phone would soon be out of date. Companion lacked any identifying qualities and tested low. Petite Phone scored high but was also considered “un-American,” as “petite” was not a word in general usage.

Princess was just right: a familiar word that was short, pleasant sounding, and easy to remember. For customers, it evoked something small, beautiful, and decorative. Dreyfuss, whose designers worked on the new phone, characterized it as “light and elegant, with a classic simplicity that stems from a purity and precision of form.” Plus, Princess was a more endearing term than the phone’s internal product designation of 701B.

In the summer and fall of 1957, AT&T test-marketed the Princess in Norristown, Pa. Two-thirds of Princess buyers were married with small children, but the next largest market segment was families with teenagers. Teens had discovered a new way to waste hours a day—talking on the phone.

When Columbia Pictures released the movie version of Bye Bye Birdie in 1963, one of the official posters featured a teenage Ann-Margret (as Kim McAfee) talking on a Princess. In the movie, the news that Kim and a boy named Hugo are going steady quickly spreads through the song “The Telephone Hour,” which includes many a Princess as well as the typical 500 and even an unrealistic car phone.

Ever since I began writing this column, I’ve looked for museum artifacts that were designed by or for women. This has been much more challenging than I anticipated. Women are traditionally underrepresented in recorded history and that extends to being underrepresented in museum collections.

And objects themselves are often gender neutral. You can’t just color something pink and call it feminine, can you? Or maybe you can, which is why I am chagrined that my first featured object with a female focus is so, well, pink.

Kira Lyle, a graduate student pursuing a dual degree in public history and library science at the University of South Carolina, was the person who first brought the Princess to my attention, when she wrote about it for an assignment in a seminar that I teach. “I was initially struck by the lovely and little nature of the pink Princess phone,” Lyle told me. When she looked at the marketing techniques used to sell the Princess, it made her consider how the phone’s introduction “reflected changes in the American family and societal perceptions of women and teen girls.”

A Princess is on display at the recently opened AT&T Science & Technology Innovation Center, in Middletown, N.J. The museum is organized around four areas: innovation, instruments, transmission, and switching. Artifacts tracing 142 years of company history include a Telstar satellite (one of four spare satellites that never launched) and an exquisite replica of Thomas Watson’s notebook where he recorded the first telephone transmission (“Mr. Watson, come here. I want you”).

Sheldon Hochheiser, corporate historian at the AT&T Archives and History Center in Warren, N.J., curated the museum and gives a virtual tour in this 3-minute YouTube video. (The Princess makes a cameo at around 2:24.)

AT&T recognizes the value of knowing its own history. The AT&T Archives—the largest corporate archive in the United States—contain over 45,000 cubic feet of documents, books, periodicals, photographs, moving images, sound recordings, and microforms, as well as 15,000 artifacts. And the new museum honors past achievements that lay the foundations for current products and research.

Like many corporate museums, this one isn’t open to the general public. The exhibits lie behind a security checkpoint and are accessible only to AT&T employees and their personal guests. The Innovation Center does not exist to tell the world about the wonders of AT&T, but rather to remind—and inspire—AT&T’s workers and perhaps to impress its customers. Engineers, designers, and even marketing executives can learn from past successes, and the occasional failure, and incorporate these lessons into future projects.

As Andre Fuetsch, AT&T Labs president and chief technology officer, said at the opening of the museum, “It’s important to know where you came from if you want to figure out where you’re going.”

An abridged version of this article appears in the February 2019 print issue as “Pretty in Pink.”

Part of a continuing serieslooking at photographs of historical artifacts that embrace the boundless potential of technology.

A correction to this article was made on 19 February 2019.

About the Author

Allison Marsh is an associate professor of history at the University of South Carolina and codirector of the university’s Ann Johnson Institute for Science, Technology & Society.