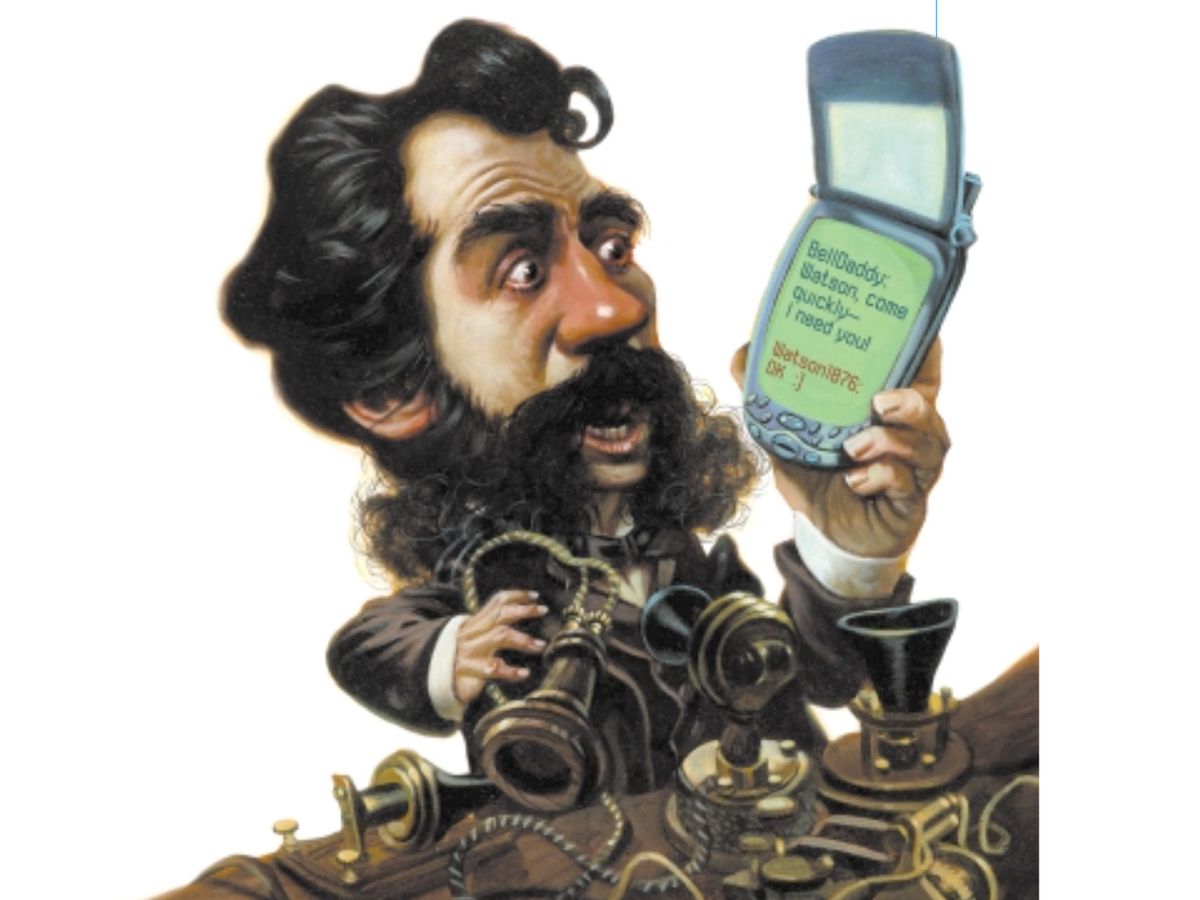

IM Means Business

Instant messaging, no longer just a facet of teenage life, now speeds everything from naval operations to customer service

Picture this: a just-in-time delivery of sheet metal arrives at the assembly line, but it has blemishes. What to do? Shut down the line? See how quickly the supplier can replace it? Use the sheets despite the defects? The line manager, Bob, doesn't answer his office phone. Every hour spent tracking him down wastes thousands of dollars.

Fortunately, the line supervisor, Alice, knows Bob's instant messaging screen name. If he is logged in on any device, be it desktop computer, cellphone, or PDA, her question will reach him wherever he is, in the office, at home, or in between.

That hasn't actually happened yet, but it's a favorite story for companies like Ikimbo Inc. (Herndon, Va.) and Jabber Inc. (Denver, Colo.). And they're just two of many software developers making instant messaging (IM) tools and programs for a field that has suddenly exploded, with applications ranging from stockbrokerage to customer service, from e-retailing to police, emergency communications, and the military.

Maybe it's even a compelling tale. Recently Ikimbo got another round of scarce investor capital, while Jabber signed up such customers as Hewlett-Packard, BellSouth, and Disney. Each is looking to tap into a market that spans over 100 million unique home users and another 18 million in offices.

A scenario that must have seemed unlikely a year ago was the U.S. Navy's Office of the Chief of Naval Operations (Washington, D.C.) turning to instant messaging when its workers were dispersed after the 11 September attacks. But it did, and now the service's top admirals are messaging their staff—and one another. Nor does the Navy's embrace of the technology stop there. Over 300 ships at sea are connected by another IM system.

As it emerges from the world of teenage chat, IM—sending text messages and, ultimately, audio, video, indeed, files of any sort, interactively—is already being put to use at corporations like IBM Corp. and Accenture Ltd. (Hamilton, Bermuda). Workers in these companies are using it to share documents remotely, to ask a quick question of one another, or to exchange notes during a meeting, despite being hundreds of kilometers apart.

IM is also moving from computers and laptops to cellphones, PDAs, and other devices. Through its prosaic "buddy list," a continuously updated window that shows who among your family, friends, or colleagues are online and available, IM connects you to your inner circle in ways that phones and e-mail can't.

What will make IM more than just the next hot idea to come and go is a single key feature called presence. In essence, this is a protocol to tell the world that you're available on a particular device. Outside IM, presence is being built into collaboration tools, word processors, e-mail directories, and even online games.

Being always available has its drawbacks, of course. All too often, work and other obligations spill over into our private time. Many find the prospect of co-workers and even family always being able to contact us daunting. Concentration can be shattered; questions that seem important to the questioner may not be so to you. If usability researchers and application developers get it wrong, presence will be a burden, instead of a benefit.

If they get it right, though, if they can deliver the right amount of your availability to the right set of people, IM can become the main way we initiate contact with the people we communicate with most often. Indeed, those now-primary forms of communication, the telephone and e-mail, will either have presence built into them, or take a back seat to IM.

Why not just call?

As a mode of interactively exchanging a great deal of information, the phone is still unparalleled. As a way to initiate communication, though, it's terrible. Until the 1970s, the phone was about as intrusive a technology as there could be. Like subjects in a Pavlovian experiment, when it rang, we responded.

Since then, we've erected walls of voicemail. By one estimate, only two in five office phone calls lead to an immediate conversation. Many of us find ourselves scheduling calls as formally as face-to-face meetings. Pagers attempt to pierce the wall of voicemail, but (except for two-way types) they're not interactive. Only unreliable caller-ID systems tell us who is calling.

The phone can also be an imposition. Erin Bradner, a post-doctoral researcher at the Institute for Software Research, at the University of California at Irvine, observes, "The recipient of a phone call is at a severe disadvantage—he or she doesn't know who is calling, or what it's about, or the urgency of the call. IM levels the playing field between sender and recipient."

Here's how: first you set up the buddy list, adding the IM system user (screen) name of those you want to be able to message. The other person need only have an account on the same system you're using, or one that can exchange messages with yours [see "IM Incompatibility"].

The buddy list tells you if someone is generally available. For example, in the AOL Instant Messenger (AIM) window, there are two tabs, one a list of everyone you've made a buddy and the other, those among them who are currently online. When your friend logs in to the system, the instant messaging server updates the application of all who have him or her on their buddy lists.

But knowing someone is logged in may not be enough—is the person really at his or her device right now? More detail can be provided through an "away" message, such as "at lunch" or "back at 3:00," which tells you the other person's status. Again, every change to their away message is pushed out to you and every other buddy list they're on.

When Alice sends Bob a message, he sees who is contacting him as well as the message itself (say, "Acme's sheet metal is defective, send it back?"), which tells him the topic of discussion. Unlike with the telephone, Bob need not respond instantly, but can shift his attention from his current task in an orderly way. If not at his desk, Bob can see the message on his return. If Alice is on Bob's buddy list as well (some experimental systems require that sort of mutuality), he'll see whether she's online to be answered.

By showing up in a little box on Bob's screen, Alice's message is as visible as the blinking light on a voicemail system, and infinitely more informative. (Having a bunch of windows popping up on your monitor raises the question of screen management; more on that later.)

Ready, AIM, fire

Corporate use of IM has soared of late, with most users simply downloading AIM or one of the other free commercial IM software packages, a practice many firms are uneasy about. One reason is security. There basically is none, and no company wants its sensitive conversations on AOL's servers. Another problem is the potential for viruses. There have been no major outbreaks yet, but IM is a perfect breeding ground for them, so one is bound to show up sooner or later.

Another knock against the commercial IM systems is that they don't work well with other desktop applications (though Microsoft Corp. has begun tackling that, at least for its own software, for example, showing presence in its Outlook e-mail directories). And some companies develop or customize software to meet a particular need. For example, the financial industry is required by law to archive all communications, even instant messages.

Hoping to exploit such opportunities, companies that provide IM applications and programming tools, including Ikimbo, Jabber, Scan Mobile Ltd. (London), and ActiveBuddy Inc. (New York City) have sprung up. They and other software manufacturers are equipping existing applications, such as the software used by customer support specialists, with IM and presence. Instant messaging is also being added to off-the-shelf applications. Groove Networks (Beverly, Mass.), for one, has added it to its collaborative work software, Workspace.

Not all applications are so serious. Disney has inserted real-time messaging in dozens of networked games, and Yahoo! has added chat functions to its Webcasts of live music performances so that "concertgoers" can interact as they do at a real concert. ELLEgirl magazine's ELLEgirlBuddy, an automated query agent, "talks" to teenagers, offering them fashion tips. IM is even being used at auto racetracks so that pit crew members can communicate with each other.

Some applications, though, are very serious. The U.S. Navy, for instance, has built presence into IM and chat functions using IBM's Lotus Sametime IM software (though with a custom Web-based interface). The software development was done by defense contractor X.Systems Inc. (Manassas, Va.).

In the aftermath of the 9/11 attacks, X.Systems built an IM application for the Navy in less than a month. Besides the larger issue of the loss of 184 lives at the Pentagon, the bombing destroyed many offices, including some used by top Navy brass. Many found themselves without access to the Navy's secure telecommunications network.

Existing plans for a general executive portal—a one-stop site for briefing documents and status reports on topics like readiness, logistics, and munitions—were tabled in favor of one particular component: an IM system that would allow the Navy's most senior officers, its three- and four-star admirals, to communicate with one another and their immediate staffs. By making the system Web-based and using secure sockets layer (SSL) encryption, it would have the needed security, even when used in temporary offices not hooked up to the military network.

IM has also been built into other Navy applications, notably the Collaboration at Sea system, a single network serving over 300 ships [see "In the Navy"]. "There are only a couple of telephones on each ship and it's a party line, so anyone on any ship can pick up a phone and listen in," says X.Systems project manager Doug Garnett-Deakin. "With Collaboration at Sea, two supply officers, for example, can IM, privately and directly."

The Navy admirals are enthusiastic about IM, though their own use of it has been spotty, according to Mary Ann Rochey, the civilian Navy manager in charge of the portal's development. "We have some admirals who totally embrace it, not just for the fleet but for themselves, and then we have some who say, 'That's something my teenager does, not me.' And then some say, 'I have the phone, I have e-mail. E-mail is overwhelming me, I'm not sure I want these people IM-ing me.' "

Cutting the clutter

The admirals aren't the only ones feeling overwhelmed. Bonnie Nardi, principal research scientist at Agilent Laboratories (Palo Alto, Calif.), says, "In our studies, people talked about 'islanding'—I'm not going to read e-mail or answer the phone until I get such-and-such done."

Besides the sheer volume of e-mail, there's what Victoria Bellotti, a senior scientist at the Palo Alto Research Center Inc. (California; formerly Xerox PARC), calls the overloading of e-mail. She found e-mail being used for exchanging documents, information management (to-do lists, contact lists), scheduling, document organization, and any number of other things for which it wasn't designed. Surprised to find workers using a single program, e-mail, instead of more appropriate software, she says, "E-mail is more like a habitat than an application."

Instant messaging should cut down on communication clutter. Schedule a meeting among a half-dozen busy people using e-mail or by phone, and by the time the last person has accepted, the first wants to suggest a different time. IM provides a way to get messages out, and answers in, almost instantly. Of course, that means interrupting people.

Studies going back to the 1980s show that some people, like department managers, want to be interrupted. Still, most research is aimed at reducing it. At AT&T Labs (Menlo Park, Calif.), user interface designer Ellen Isaacs and her colleagues learned to use sounds to signal, for example, that someone on one's buddy list had come online. Such sounds were much less disruptive than new text appearing on-screen. Microsoft's adaptive systems and interaction group, part of Microsoft Research, has found that messages relevant to the current task may not be disruptive at all.

Then there's the question of having multiple windows pop up on your screen, which happens when several people IM you at the same time. Teenagers can hop between a dozen IM sessions at once, each in a separate window. Most grownups, though, can't keep that many conversational balls in the air.

Eric Horvitz, manager of the Microsoft group, says, "We need to build attention managers instead of windows managers," which would reason about a user's context. Using camera- and microphone-like sensors, they could determine the user's focus. If your head is down, the system can assign a higher probability that you're concentrating on something; voices suggest you're engaged in a conversation; and so on. Virtual visitors would be advised to come back later.

Ultimately, Horvitz says, you also need to ask not whether an interruption has occurred, but if it was worthwhile. "Can giving someone a little bit of info save them a lot of time, even though it costs you a little time?"

But Michele Tepper, a Web usability specialist at IBM and frequent IM user, is one of many worried about extending presence beyond a small handful of people. "Attention is our most limited resource," she says. PARC's Victoria Bellotti worries that IM could become as overloaded as e-mail.

Managing the away message

Better management of one's away message, which users never seem to keep up-to-date, would help to keep IMs to manageable levels. Bill Buxton, chief scientist at Alias/Wavefront, a Toronto subsidiary of Silicon Graphics Inc. (Mountain View, Calif.) and a faculty member in the University of Toronto's department of computer science, thinks the task needs to be automated. He notes that some high-end automobiles lower the radio volume when the car's cellphone rings. "We need a lot more of that," he says.

For instance, a closed office door should indicate you're less available to those communicating with you electronically, just as it indicates to those passing by you're less available in person. (Sensors to do that have been built experimentally.) In another pet example of Buxton's, if your desktop computer hasn't registered a keystroke in 10 minutes, and you've just used your cellphone, then IM should go to the cellphone, not the computer, without your having changed any settings on either device.

Microsoft's Horvitz thinks we can automate the decision of whether to contact someone and which form of communication to use. One system, called Coordinate, forecasts the user's situation. "It's not whether you want to talk to a person now, but when you would want to talk to a person," he explains. "We look across a user's multiple machines at patterns of presence and absence."

The system could respond to a piece of e-mail or an IM that, for instance, the user is 85 percent likely to be back in the office within 20 minutes. (Another program, TimeWave, takes those educated guesses about when someone will be back in the office and posts its predictions on his or her electronic calendar.)

Microsoft's latest effort is a notification system called BestCom. (The name is short for something like best form of communication.) When you want to communicate via BestCom with someone, the pre-set preferences of the person are consulted. Horvitz describes one scenario: "Say I revise a Word document that my collaborator has made. Instead of just e-mailing it, one option is to BestCom it. The system then makes a decision whether to attempt real-time contact [such as IM], store-and-forward contact [such as e-mail], or a future real-time contact."

It's hard to predict whether users will welcome such automated assistance or resent it. It's also hard to be sure instant messaging will be embraced without it. But already some users are largely abandoning e-mail in favor of IM, including this writer's 16-year-old daughter. When I asked Bellotti of PARC about that, she said that her research agrees. "Teens hardly use e-mail, and when they do, often it's merely to exchange documents, or to communicate with the adult world," she says. (It's no coincidence that teenagers use mobile technology more, and desktop technology less, than adults, especially in Europe and Japan, where most teens have their own cellphones but limited access to a desktop computer.)

Then there's one particular behavior of those Navy admirals. Rochey points out that some of them will use the presence information without using IM. They'll say: "Hey, it [the presence indicator] is green, I'll call." Some day soon, presence will get built directly into telephones (especially as telephony moves to cellphones and the Internet), e-mail, and many other applications. For better and for worse, our virtual selves will soon be everywhere always.

To Probe Further

Much of the human-factors research on attention, presence, and instant messaging (IM) can be found online. For example, in "Interaction and Outeraction: Instant Messaging in Action," Bonnie Nardi, Steve Whittaker, and Erin Bradner discuss how users choose their mode of communication, whether e-mail, instant messaging, or the telephone (https://www.research.att.com/~stevew/outeraction_cscw2000.pdf)

In "Email as a Habitat," Nicolas Ducheneaut and Victoria Bellotti describe the wide variety of tasks for which simple e-mail gets used (check into https://www.sims.berkeley.edu/~nicolas/documents/Ducheneaut-Bellotti-Email_as_habitat.pdf).

Two articles by Microsoft researchers explore the tradeoff between alerting and interrupting: "Attention-Sensitive Alerting" by Eric Horvitz, Andy Jacobs, and David Hovel (https://research.microsoft.com/~horvitz/attend.htm) and "Instant Messaging: Effects of Relevance and Timing" by Mary Czerwinski, Edward Cutrell, and Eric Horvitz (https://research.microsoft.com/users/marycz/hci2000.pdf).

Six years of work by a number of researchers on the question of adding computer-based awareness to social spaces are recapped by William A. S. Buxton in "Living in Augmented Reality: Ubiquitous Media and Reactive Environments" (https://www.dgp.toronto.edu/OTP/papers/bill.buxton/augmentedReality.html).

Wireless Village is an IEEE Industry Standards and Technology Organization initiative. Information on the initiative is available at https://www.wireless-village.org/.