Google has gotten better at forgetting. A year ago, a European court ruled that Google search results in the European Union were subject to European data-protection rules. That meant that while private individuals might not be able to force a newspaper to retract an irrelevant or outdated story about them, they could ask Google to remove links to the story. Despite a slow start, the search giant has now caught up with the requests. In the meantime, Americans, Japanese, Koreans, and others around the world are proposing the adoption of similar privacy-protection policies.

Google—which can claim 93 percent of the European search market, according to StatCounter—began removing certain links from search results on its EU pages in June. The removals were in response to a 13 May 2014 ruling by the Court of Justice of the European Union that enables residents to request the removal of search engine results that point to prickly parts of their past. If it did anything, the ruling proved that personal privacy is popular: Google got over 41,000 requests in the first four days it accepted them. Requests later leveled off at around 1,000 per day.

The off-line analogy might be a guest asking a party host not to bring up an old, reputation-tarnishing story. It is still up to the host to decide whether to comply, and other guests may still whisper—or shout. But thanks to the CJEU ruling, search engine results in the EU are now subject to the same data-protection rules as other company-held personal data. It’s as if party attendees could now ask the party host to keep mum, with the threat of appealing to a national agency.

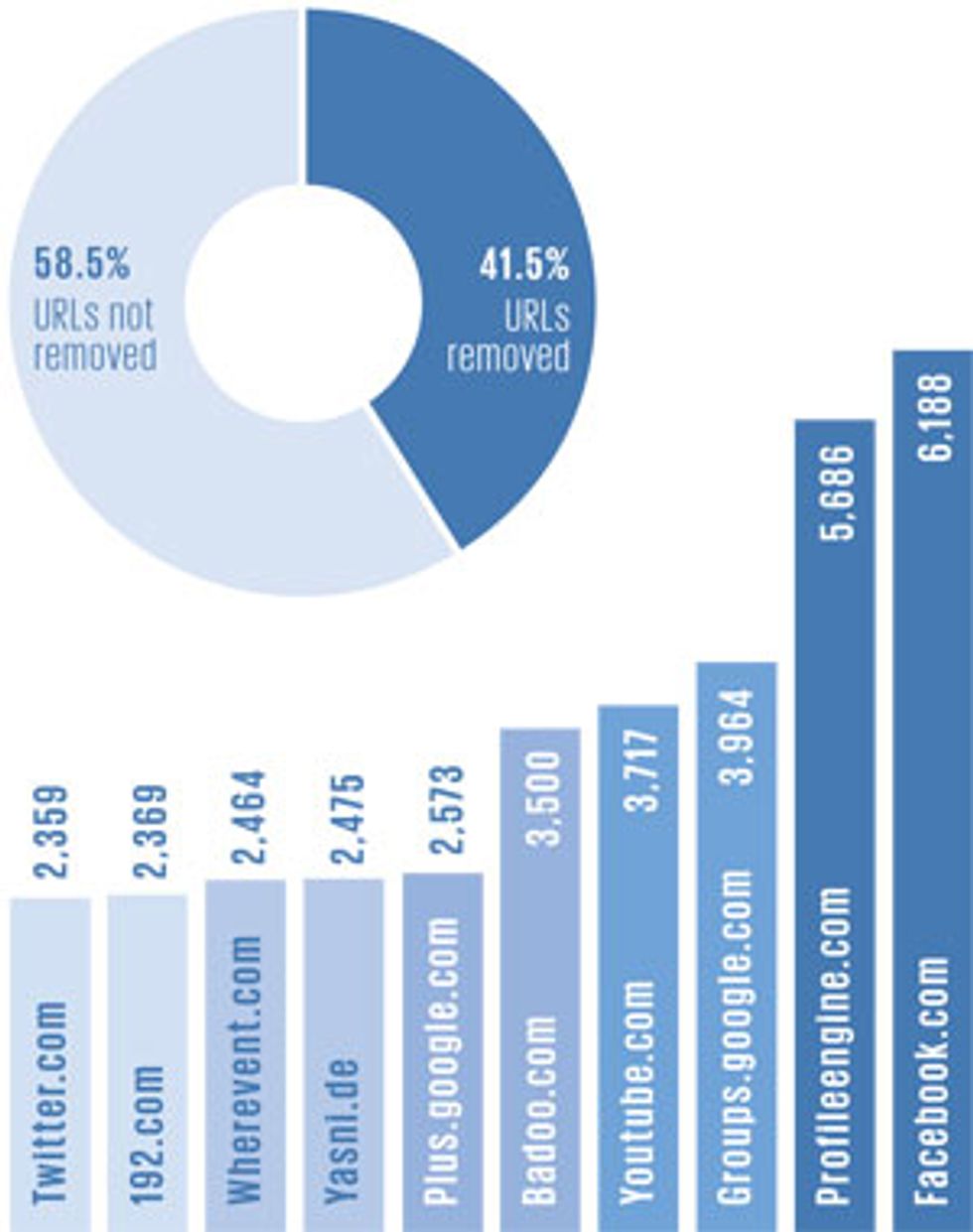

Yet the ruling left open many questions about how to comply. Soon after removals began in June, for example, Google restored certain links when publishers argued that the stories in question were in the public interest. Individuals unhappy with the decisions of search engine providers—Google has rejected a little over 40 percent of requests so far—can still appeal to their national data-protection agencies.

The logic that the ruling follows is one of the things that makes it remarkable. The ruling skips altogether the mechanics of how search results are created from public third-party records. Instead, the court reasoned that the potential richness and accessibility of search results make them more of a threat to a person’s privacy than the individual records themselves. Since Google (for now) is the main controller of that data in Europe, it has the same responsibility as other companies that control personal data in Europe, the court argued.

Yet some groups have questioned the court-imposed, company-implemented method of protecting the public’s right to know: “We argue that it should be handled by a court, not a company,” says Pam Cowburn, communications director for the Open Rights Group in London.

Wikipedia founder Jimmy Wales, who sat on an advisory council that Google convened about the issue, concurred in his comment on the council’s report and added that “the recommendations to Google contained in this report are deeply flawed due to the law itself being deeply flawed.” Google’s advisory council conducted hearings in seven European cities in late 2014.

Another member of the advisory council, German federal justice minister Sabine Leutheusser-Schnarrenberger, argued that Google’s current interpretation of the ruling does not go far enough. “Since EU residents are able to research globally, the EU is authorized to decide that the search engine has to delete all the links globally,” she wrote in her comment on the report.

And globally is how the idea is spreading. A Japanese court ruled in October 2014 that Google must take down some personal information. Yahoo has already announced that it will extend its existing privacy takedown request system to its Japanese sites. Hong Kong’s privacy commissioner for personal data, Allan Chiang Yam Wang, said late last year at the Asia Pacific Privacy Authorities Forum in Vancouver, B.C., Canada, that national privacy officials from many countries were considering how they might enact their own versions.

The question in all cases is whether unfettered search engine results are the same as free expression. There’s good reason to think not. Governments limit the intrusiveness of credit reports, for example, treating them as business tools instead of a form of free expression. Evgeny Morozov asked in The New Republic, “If we don’t find it troubling to impose barriers on the data hunger of banks and insurance companies [for composing credit reports], why should we make an exception for search engines?”

At a March debate presented by Intelligence2, University of Chicago law professor Eric Posner argued that such information is now easier to find than in the past, when public records such as trial proceedings might have ended up in a courthouse basement—available, but not easily accessible to all. “What the ‘right to be forgotten’ does is it raises the cost for strangers to find out information about you. It doesn’t make it impossible,” he said. By making it inconvenient, but not impossible, for someone to find contested information, the right to be forgotten is effectively undoing some of the gains of the information age: re-creating the effect of paper’s archival limitations with today’s technology.

This article originally appeared in print as “Google’s Year of Forgetting.”

About the Author

From Madrid and Central America, Lucas Laursen covers odd things for IEEE Spectrum, such as an effort to turn snails into fuel cells and how to tell when a hen is plotting murder. For the May 2015 issue he travelled to Nicaragua to report on a rural electrification project.