Frank Miller was a banker, which makes it surprising that he made an important contribution to cryptography. Now credited as the first person to invent the one-time pad, a simple yet effective way to encrypt a message by shifting each letter by a random number of positions to a new letter in the alphabet, Miller’s achievement would have been lost if it hadn’t been for some fortunate circumstances.

In this month’s IEEE Spectrum article “The Future of Cybersecurity Is the Quantum Number Generator,” authors Carlos Abellán and Valerio Pruneri explain that Miller discussed the one-time pad in his 1882 book Telegraphic Code to Insure Privacy and Secrecy in the Transmission of Telegrams. That means Miller, who lived in Sacramento, Calif., in the late 19th century, was thinking about the one-time pad at least 35 years before the long-assumed inventors, Bell Labs engineer Gilbert S. Vernam and U.S. Army Captain Joseph Mauborgne, proposed the idea.

Now we have Steven Bellovin, a professor of computer science at Columbia University, to thank for bringing Miller’s contributions to light. “I had some spare time in Washington D.C., seven and a half years ago,” says Bellovin, “so I decided to go to the Library of Congress and see what they had.” Among the library’s vast collection, Bellovin was looking for very specific books: old telegraph codebooks.

Bellovin collects old telegraph codebooks as a hobby. By the time of his D.C. trip, he already had a substantial personal collection. “By this point, I had a good idea of how 19th-century cryptography worked,” Bellovin says. Those early systems were not very robust, favoring brevity over security—after all, telegraph companies charged by the word, so if you could encode an entire commonly used phrase in a single word, you saved a lot of money. It was Miller’s emphasis on security at the cost of brevity that made his book stand out to Bellovin.

“I found some titles with ‘secrecy’ or ‘privacy’ in the title. One was Frank Miller’s,” Bellovin says. “I opened Miller’s and said, ‘My God, that’s a one-time pad!’ ” There were a few things that made it clear to Bellovin that Miller was onto the idea of the one-time pad. In his book, Miller discussed the importance of using random numbers. Secondly, he stressed the importance of no repetitions in the numbers used. Lack of repetition denies anyone attempting to decode the message a predictable pattern that might be used to unravel the secret message.

This was more than enough to pique Bellovin’s interest. “My immediate question was, who was this guy?” Bellovin sent emails to David Kahn, who has written extensively about the history of cryptography, as well as the Center for Cryptologic History, to see if anyone had heard of Miller. Then Bellovin started poking around online to see what he could find. “Before I went to bed that night,” says Bellovin, “I had a tentative idea of who he was.” Which was just as well, because neither Kahn nor the Center for Cryptologic History had any idea who this mysterious Miller was.

It certainly was lucky that Bellovin, with his interest in 19th-century telegraph cryptography, was the one to come across Miller’s book in the Library of Congress and recognize its value, but Bellovin himself notes he had two additional bits of luck in identifying Miller.

“One stroke of luck was that he became prominent in late 19th-century California,” says Bellovin. “All of the big families in that area were connected to the Union Pacific, and his family was connected somehow.” That was enough for Miller to leave his mark on Californian society. The second stroke of luck was that one of Miller’s descendants wrote a family tree book, preserving a record of Miller after his death.

Of course, we’re talking about a man who wrote a telegraphy book almost 140 years ago before fading into obscurity. It’s impossible to identify him with absolute certainty. Still, Bellovin is as confident as he can be. “There were two Frank Millers in Sacramento in 1880, and the other was a laborer,” says Bellovin. Between the two choices—the banker or the laborer—the banker was the one likely thinking about telegraph encryption. “I’m virtually certain I’ve identified the right Frank Miller,” Bellovin says.

Bankers in the 1880s spent a lot of time working with telegraphy. After all, telegrams were the method of choice for long-distance transactions. If Miller the banker was the correct Miller, it’s clear that he was less concerned about saving money on telegraphs, and more about preventing money from being stolen via telegraph. In an era where the Wild West wasn’t quite dead and train heists by robber gangs weren’t unheard of—possibly aided by telegraph operators leaking relevant information—keeping financial transactions secure was just as important as it is today. Miller’s reasoning was likely that a telegraph operator couldn’t leak information he couldn’t understand.

There’s also some circumstantial evidence that Miller was thinking about cryptography after a stint in the military working with encryption during the end of the Civil War, including time potentially spent as a member of the team investigating Lincoln’s assassination. Bellovin says there’s some mention of this in the genealogy book he uncovered, but he wasn’t able to verify Miller’s involvement with much certainty.

However, there were limits to Miller’s suggestions for security. There were the technical limitations, for one—there was no way to generate truly random numbers in the 1880s, and many of the techniques we have today are cumbersome or expensive.

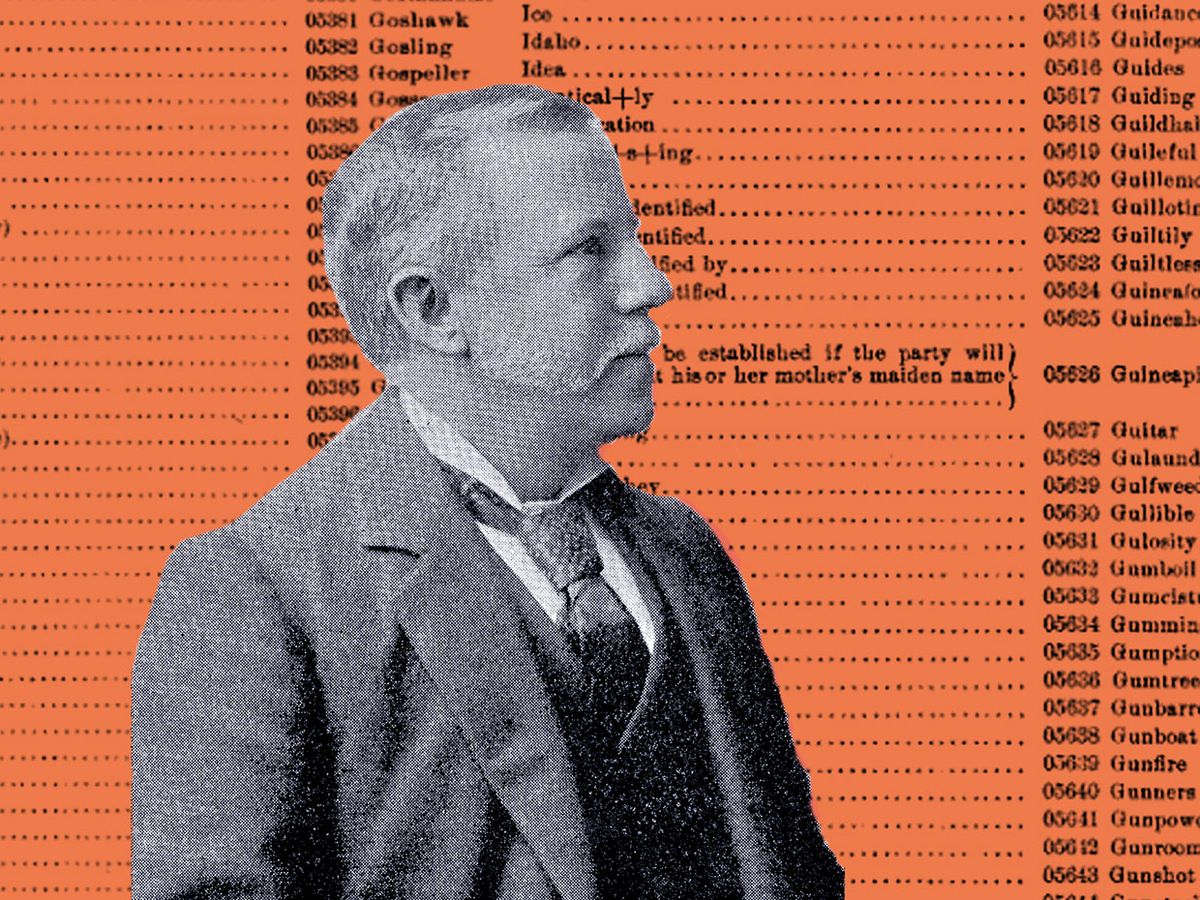

Even so, Miller’s ideas lacked rigor in other respects. For example, it was important to authenticate the identity of the telegram recipient, especially for financial transactions. Miller’s suggestion was to include a code word like GUINEAPIG in a telegram, followed by the recipient’s mother’s maiden name.

A banker who received a financial transaction by telegram and saw that it included the phrase “GUINEAPIG Smith” would know he was talking to the right person by asking him what his mother’s maiden name was and hearing him answer “Smith.”

Of course, if anyone intercepted the message and was familiar with Miller’s codebook, he would also know what evidence he needed to present to prove he was the intended recipient. Even in the 19th century, it wouldn’t be hard to track down someone’s mother’s maiden name, making Miller’s suggestions for authentication as plagued with problems as today’s security questions are.

And there’s some evidence that others were reading Miller’s book. Bellovin has tracked down three copies of the book—aside from the copy at the Library of Congress, the New York Public Library and the University of Chicago library also have copies in their collection. Bellovin says the New York Public Library’s copy is a second edition, suggesting there was at least some interest for Miller’s ideas.

Bellovin says it would be great if he could prove that Vernam and Mauborgne were aware of Miller’s work, thereby demonstrating that Miller alone was the inventor of the one-time pad. For now, it’s impossible to tell if the men independently developed the idea or if they were inspired by the banker’s work. There’s a possible connection—at one time, Miller and his daughter Edith attended a military ball. One of the officers attending was Parker Hitt, a cryptologist and, crucially, Mauborgne’s mentor. If Miller discussed his ideas with Hitt at the ball, says Bellovin, it’s possible Hitt relayed the ideas to Mauborgne and ultimately Vernam.

“It would be really interesting to prove a direct link,” says Bellovin. “But there’s strong evidence for an indirect link.” But that’s why Bellovin says this is exactly the sort of question that makes history so important. At the end of the day, whether Vernam or Mauborgne independently developed the idea of the one-time pad or were inspired by Miller is a small part in the history of cryptography. But now that we know it exists, we have a fuller understanding of how cryptography developed. “It’s one more small link in that whole story,” Bellovin says.

Michael Koziol is an associate editor at IEEE Spectrum where he covers everything telecommunications. He graduated from Seattle University with bachelor's degrees in English and physics, and earned his master's degree in science journalism from New York University.