Photonics engineers dream about using light to zap data between processor cores on multicore CPU chips. By replacing copper wires, such optical interconnects could make chips much faster and more power efficient. The holy-grail for optical on-chip communication is a laser made of silicon.

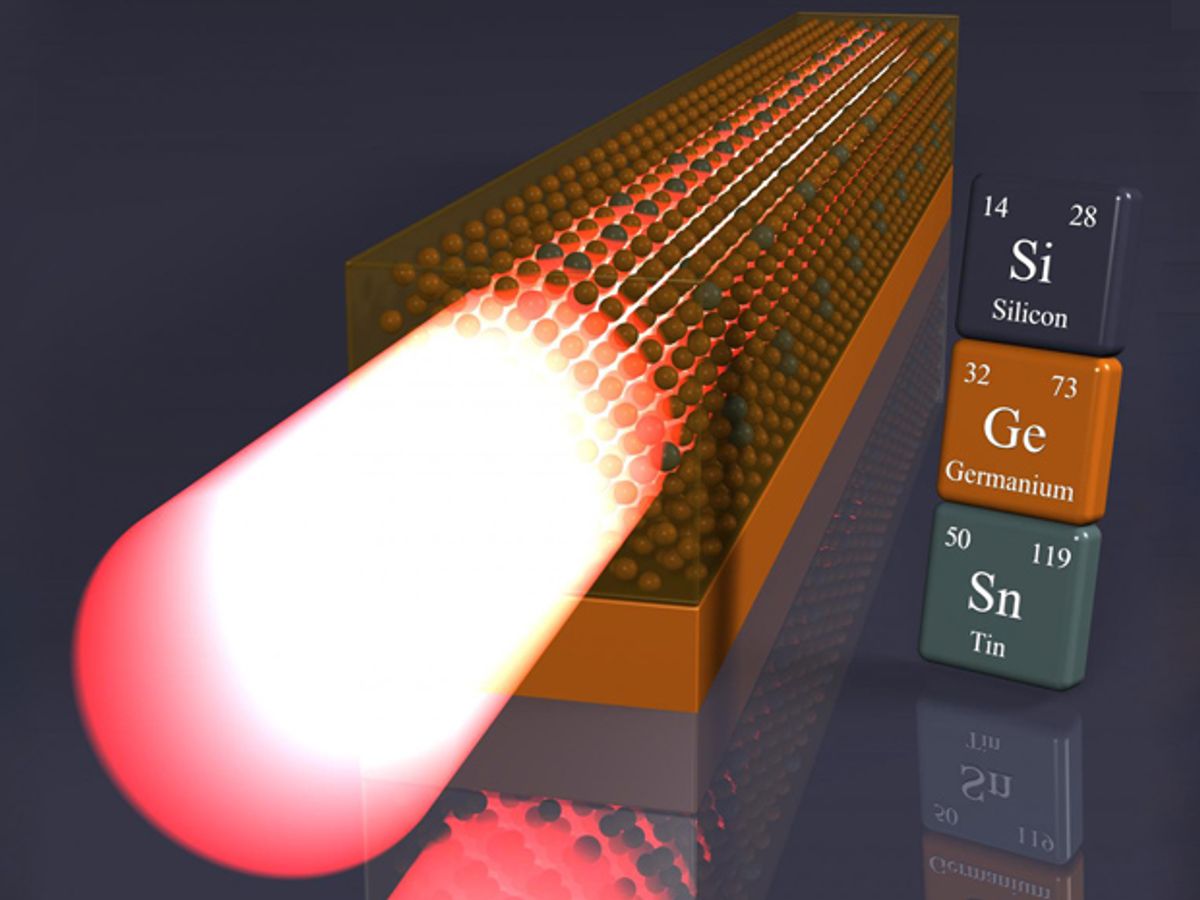

Now a European research team has built a germanium-tin laser that they say could be used instead. Germanium and tin, like silicon, are group IV elements, which means their crystal layers can be grown directly on silicon. So a germanium-tin laser would be compatible with silicon manufacturing processes.

The proof-of-concept laser, reported in the journal Nature Photonics, operates at-183°C and is powered by light instead of electricity. But the researchers’ eventual goal is to make an electrically pumped laser that operates at room temperature.

One approach for optical interconnects is to make compound semiconductor lasers separately and then bonding them to silicon chips. Intel and Luxtera have, for example, made on-chip communication systems using hybrid silicon/indium phosphide lasers bonded on silicon. But some engineers believe that for mass production creating lasers directly on silicon would be more cost-effective and less error-prone.

The problem with germanium and silicon is that they are bad light emitters, because they have an indirect band gap. When electrons in the materials are excited by light or electricity and then drop back to their lower-energy states, they emit the excess energy as heat instead of light.

Scientists have managed to tease light out of silicon nanowires. And some researchers have engineered germanium’s band gap to make a laser by doping it with phosphorus or putting it under mechanical strain.

The research team from Forschungszentrum Juelich in Germany and the Paul Scherrer Institute in Switzerland gave germanium a direct band gap by alloying it with tin; the resulting material has a tin concentration of 9 percent. They made the laser by growing the germanium-tin layer on a germanium layer that they grew directly on a silicon wafer.

The new laser emits light at a wavelength of 3 micrometers, which the researchers say makes it suitable for detecting carbon compounds as well. And the laser could have other uses, according to the press release:

Gas sensors or implantable chips for medical applications which can gather information about blood sugar levels or other parameters via spectroscopic analysis are examples. In the future, cost-effective, portable sensor technology —which may be integrated into a smart phone—could supply real-time data on the distribution of substances in the air or the ground and thus contribute to a better understanding of weather and climate development.

Prachi Patel is a freelance journalist based in Pittsburgh. She writes about energy, biotechnology, materials science, nanotechnology, and computing.