George Devol was only 9 years old when the word “robot” first appeared, in 1921, introduced in Karel Capek’s play R.U.R. (Rossum’s Universal Robots). The robots in the play had a human form and were manufactured in vats like beer. In contrast, the robots that Devol would invent decades later were electromechanical machines—the first digitally operated programmable robotic arms—and they would start a revolution in manufacturing that continues to this day.

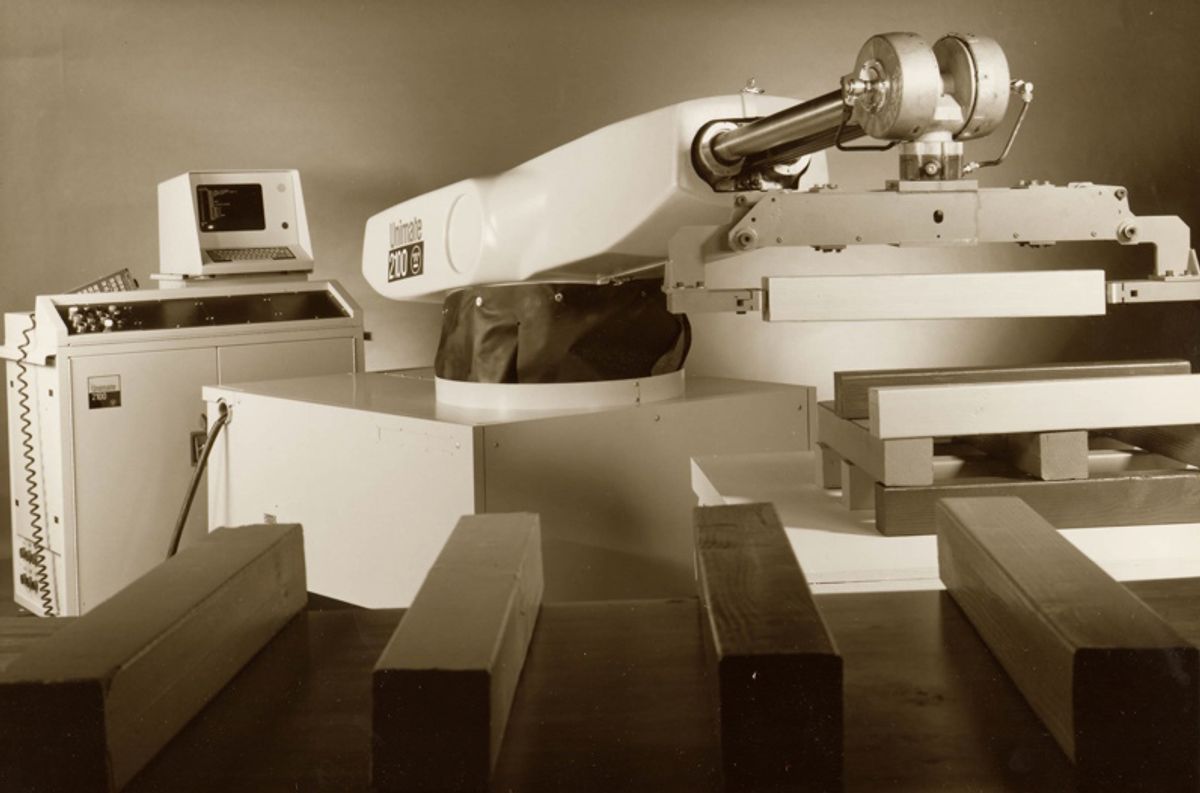

Devol, who died August 11, 2011, at the age 99, was a prolific inventor and entrepreneur. His work led to the development of the first industrial robot, called Unimate [photo above], a precursor of the machines that now automate assembly lines all over the world. But the industrial robot was only one of his contributions. With over 40 patents under his belt, Devol spent his lifetime transforming ideas into real products.

Born into wealth in Louisville, Kentucky, George Charles Devol, Jr. became interested in electricity and machines at an early age. He attended Riordan Prep and gained some practical experience helping run the school’s electric light plant. But he didn’t go to an engineering school upon graduation. He started a company.

It was a time when the age of electric motors and generators, control engineering, electrical transmission, and radio technology was in lift off. The first sound films, known as “talking pictures” or “talkies” cried for better sound integration, and Devol saw an opportunity. He used his experience with vacuum tubes, photocells, and circuits to form United Cinephone Corp., in 1932, trying to gain a position in film sound.

But the competition drove him to other pastures. Using the photocells and vacuum tubes he knew so well, he ended up creating one of the technological marvels of the modern world: the automatic door. He licensed the technology to a firm called Yale & Towne, which commercialized it as the “Phantom Doorman” photoelectric door.

Devol went on to work with color printing presses and packaging machines, and eventually develop an early form of bar coding, and later, digital magnetic recording. He was moving ever closer to robots.

In 1939, Westinghouse displayed Electro the robot at the New York World’s Fair. It was a large clanking, talking theatrical fulfillment of all those pulp and science fiction images that dominated the newsstands—some of which were read by Devol.

In fact, in 1941 Isaac Asimov coined the word “robotics” in his story “Liar!” in Astounding Science Fiction magazine. Asimov told me in great detail when we met one evening in New York why he coined the word. He was tired of listing all the activities around robots such as design, construction, operations, manufacturing, etc. He wanted a word to cover all of this. He did not know at the time that Devol was already the living embodiment of robotics.

During the World War II period, Devol worked at Sperry Gyroscope, where he helped develop radar systems and microwave test equipment. Later he organized General Electronics Industries in Greenwich, Conn., which would become one of the largest producers of radar and counter-radar devices.

After the war, he worked on several other inventions. He was part of a team that developed the first microwave oven product, the Speedy Weeny, which automatically cooked and dispensed hotdogs.

In 1954, Devol applied for a patent for a device called the Programmed Article Transfer. Looking for an entrepreneurial partner, Devol found one, at a cocktail party, by the name of Joseph Engelberger, an executive with engineering degrees from Columbia University. Engelberger, who shared an enthusiasm for science fiction with Devol, took the transfer machine to his heart, he told me during an interview in 1977.

Their device morphed from “programmed article transfer” to “manipulator” to “robot.” Devol and Engelberger made this decision to help improve their marketing opportunities. Selling the concept even with a working prototype was an uphill chore. But it paid off: The robot connection gave the project an extra dose of energy that helped it succeed.

The first Unimate, a product of their new Unimation Corp., was hydraulically powered. Its control system relied upon digital control, a magnetic drum memory, and discrete solid-state control components. In 1961 the first Unimate was installed at a GM plant in Trenton, New Jersey, to assist a hot die-casting machine. Unimation would soon develop robots for welding and other applications. Patent Number 2,988,237 was the seed that spawned the robot industry.

In one of my encounters with Devol, at the 1997 Automation Hall of Fame ceremony, I presented him with an award. During the reception, Sico, an entertainment and educational robot, rolled over to Devol and said, “Father, so good to see you!” A smile broke over Devol’s kind face, and we all laughed.

In a subsequent conversation Devol told me that none of his inventions were accepted quickly or easily. His persistence—99 years of it—made the world a different place. May whatever robot angels exist lift you up and let you rest in peace.

Images: Bob Malone