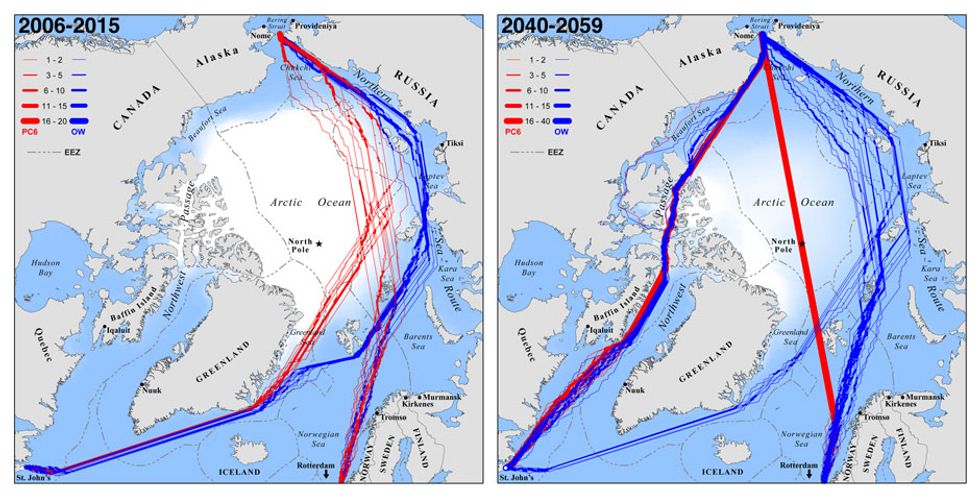

By the middle of this century, ships should be able to ferry cargo between Europe and Asia by cutting straight across the North Pole, cutting their travel times in half. Geographers at the University of California, Los Angeles, have combined sea-ice coverage predictions with geographical and transportation models to compute this and other Arctic sea routes for the first time.

By midcentury, as the warming climate decreases Arctic ice levels, ice over the North Pole will be so thin that ice-breaking ships will be able to cut through it, but only in late summer, says Laurence C. Smith, a professor of geography at UCLA. However, other recently opened Arctic sea routes that are currently hard to navigate will become easily accessible for longer periods of time, even to ordinary ships.

The researchers’ findings, published in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences Plus, are limited to September, when Arctic ice is thinnest and easiest to navigate. But Smith expects similar patterns to emerge for the two- to four-month period before and after September.

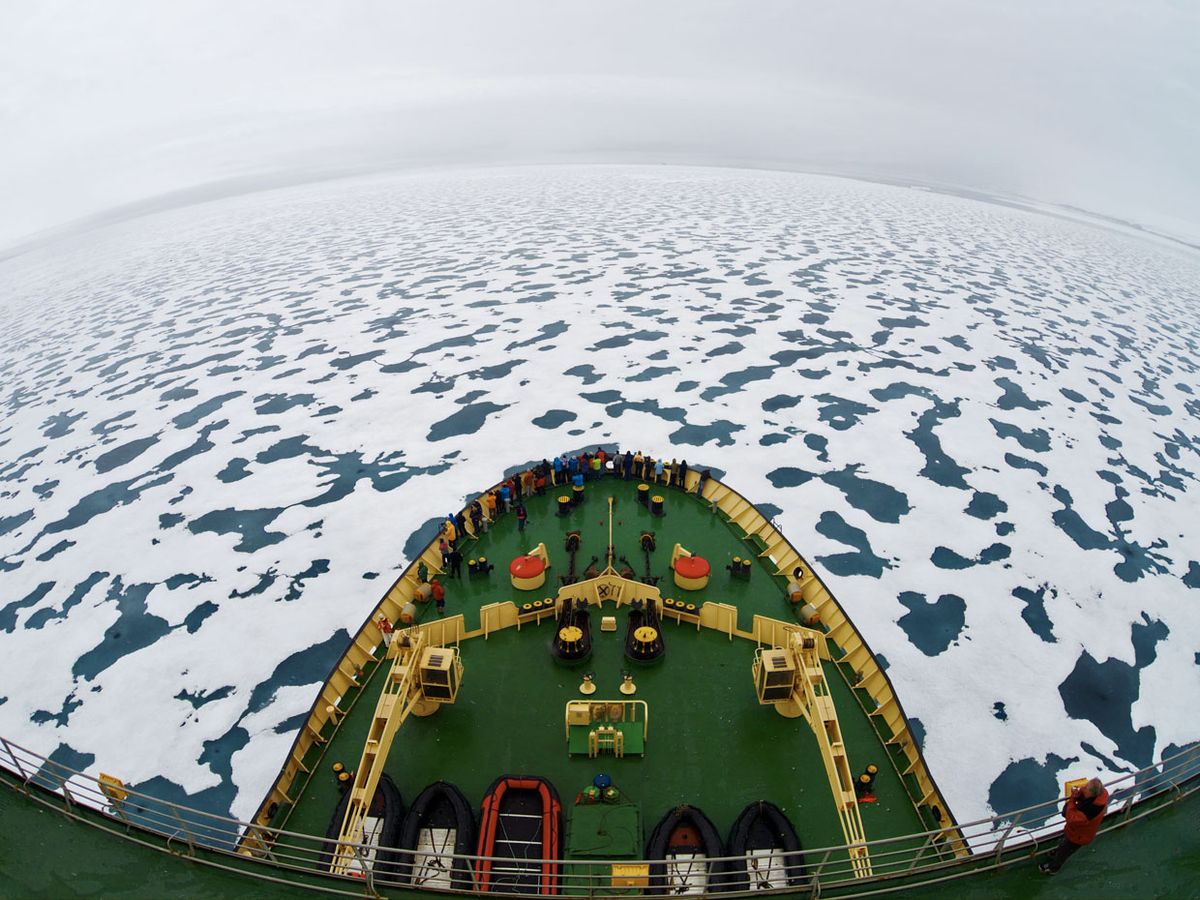

Arctic passages could be much shorter than the routes ships use today when traveling between Asia and Northern Europe or North America, and that means fuel savings. More important, the routes could make it easier to extract oil and natural gas in the Arctic. “During the month of September, icebreaker vessels would have unfettered access to the Arctic,” Smith says. “Of course, the biggest detriment would be increased activity and human presence in one of the last pristine places on Earth.”

Record-low summer ice in the Arctic over the past two years has already opened up the Northern Sea Route (NSR), which traces the northern Eurasian coast. The route is about 40 percent faster than the Suez Canal for ships traveling between the Netherlands and Japan.

In 2005, there was a 40 percent chance that ordinary ships could navigate through the NSR in September. (Only 46 ships made it through the NSR in the summer of 2012.) But the UCLA researchers predict that from 2040 through 2059 the absence of ice would give ships an almost 100 percent chance to go through. During that same time period, the route directly over the North Pole, which is accessible only to icebreaker ships, would be even shorter: the distance between the Bering Strait and Rotterdam, The Netherlands, is 8500 kilometers via the NSR and 7100 via the North Pole.

Smith and his graduate student Scott Stephenson started with seven global climate models, developed at institutions around the world, that replicated the thickness and extent of Arctic ice. The researchers averaged the predicted September ice conditions for every year between 2040 and 2059. They used a geographic information system tool to analyze the percentage of ice covering each area and transposed it with the underlying land and water topography, as well as transportation industry rules for how much ice ships can safely cross. This allowed them to compute the fastest possible routes.

The results are conservative, Smith says. Recent satellite data show that September ice levels have been falling more dramatically than models report. “I wouldn’t be surprised if some of these Arctic shipping routes opened up sooner,” he says.

Greater access to the Arctic could have interesting geopolitical implications, says Malte Humpert, executive director of the Arctic Institute, in Washington, D.C. Russia today requires icebreaker escorts and charges a fee for the service to ordinary ships crossing the NSR. As these ships have greater access to the route, he asks, “How would Russia respond to this loss in revenue?”

Humpert goes one step further than the UCLA researchers. He predicts that by 2050, even ordinary ships, not just icebreakers, should be able to use the North Pole route for two to three months. And because this route is beyond Russia’s economic zone, it could be beneficial to other countries, such as China.

Even with less ice, the Arctic will remain a treacherous environment, with ice floes, storms, and winds that can push ice into a ship’s way. Both Smith and Humpert say regulations to cover environmental protection and ship safety are urgently needed.

About the Author

Prachi Patel is a contributing editor to IEEE Spectrum. In February 2013, she reported on a new kind of implant that could allow scientists to control brain using light.