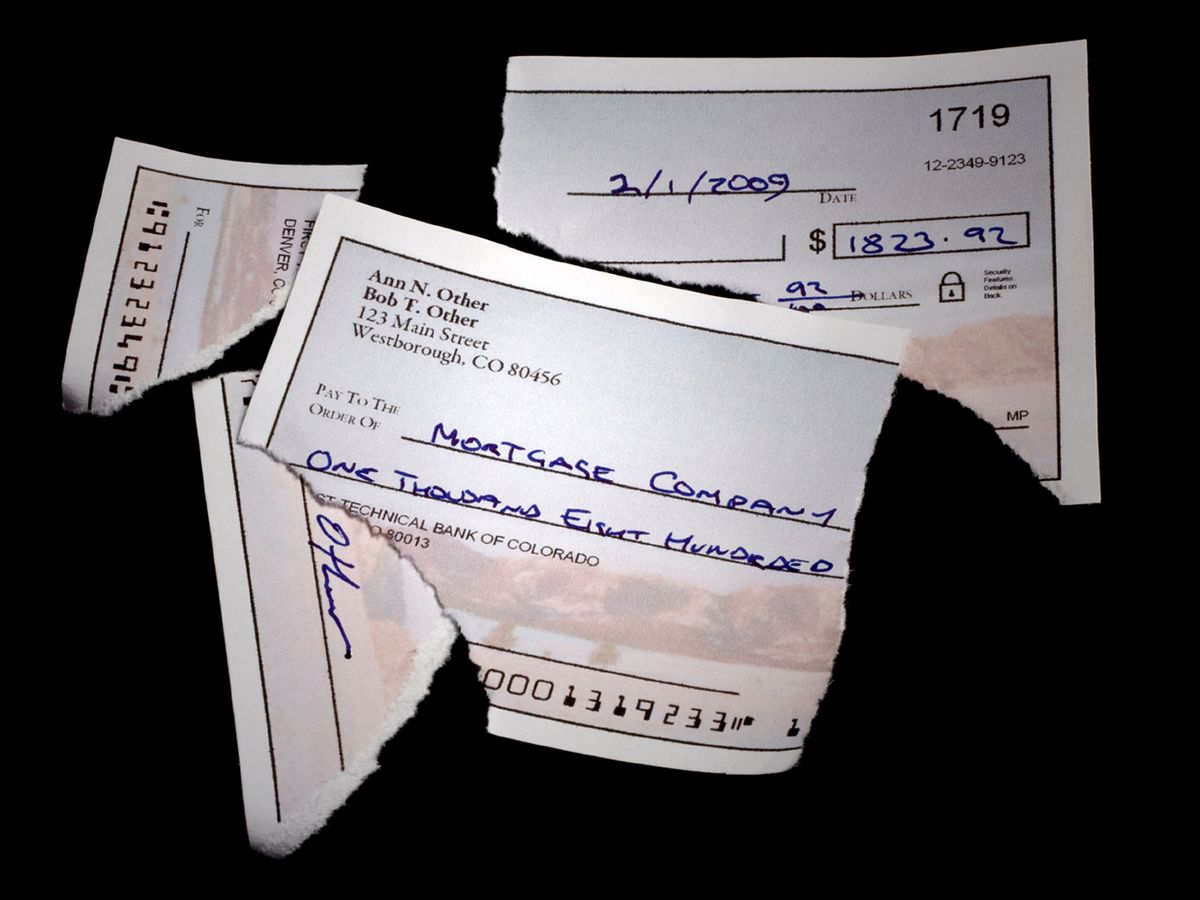

Don’t Write Off Checks

Like the paperless office, a check-free society is still far off

One of the oldest forms of payment recently came dangerously close to cashing in its chips. Britain’s Payments Council, a nongovernmental organization in the United Kingdom responsible for overseeing the nation’s noncash monetary systems, ruled in 2009 that “cheques” (as it is spelled in the U.K.) would be abolished from the country entirely by 2018.

But last year the council rendered a surprise stay of execution for this often overlooked payment method. “The cheque,” states council chair Richard North on the organization’s website, “is staying.”

Despite the emergence of online payment systems like PayPal and Bitcoin, swipeable payment chips, and smartphone money apps—as well as plain old debit, credit card, and online bill pay schemes—paper checks don’t seem to be disappearing.

“There’s a bias among many to think that because it’s paper and because it’s handwritten, it’s got to be horribly inefficient and costly,” says Alan Frankel, an analyst at the Chicago-based consulting firm Coherent Economics. “I think that’s a myth. For the check transactions that are still used, they tend to be low-cost.”

Frankel says that in the United States, fierce competition among banks over the past 60 years—as well as some strong-arming by the U.S. Federal Reserve System—led over time to banks slashing the fees they charge for honoring one another’s checks. Many grocery stores still accept checks, for instance, because it can still be substantially cheaper to accept them compared to accepting a credit card, which clears over more expensive proprietary networks that reap substantial fees for the credit card companies. [You can see a comparison of transaction fees here.

The same is true for larger transactions. Consider making a down payment on a new car—the dealership might lose close to US $100 off the top in fees for a credit card transaction or a lesser but still substantial amount for a PIN debit charge. The fee for the check itself, on the other hand, could be as low as zero. The main cost, in fact, comes from the occasional bounced check, but the amortized expense is still small.

"The merchant's risk of loss on a check is tiny: They or a lender can always come back and get the car from you," Frankel says. "But electronic payment shouldn't cost that merchant more. It should be less. The costs aren't technology costs. They're all fees that have no relationship to any costs—commissions going to the [credit card] issuing banks. In any sane world, it’d be cheaper to get paid by a debit card than a check.”

Despite those out-of-whack fees, the vast majority of transactions today are more simply and conveniently handled electronically, and check usage in aggregate is therefore dwindling. The number of checks written in the United States, for example, dropped about 20 percent from 2006 to 2009, the last year for which the Federal Reserve has complete data. The decline in the U.K. has been even more dramatic. According to Sandra Quinn of the Payments Council, check use declined 40 percent between 2007 and 2011.

Institutional inertia is perhaps the main force keeping checks around, says Bob Meara, a senior analyst in the banking group of New York City consulting firm Celent. “The pay cycle among businesses can be really large and complex,” he says. “You’ve got purchase orders and internal approvals. If you look at the total cost to process that payment, it’s huge. And much of it is manual—paper going back and forth. So if the payment was made electronically, frankly, so what?”

Checks also represent convenience when it comes to social institutions. Consider, says Frankel, a $100 wedding gift. “You may not even know the name of the new married couple,” he says. “With a check, you can do that. Without going through a lot of hassle, you can’t do that in another way.”