The views expressed here are solely those of the author and do not represent positions of IEEE Spectrum or the IEEE.

Many people seem to regard facial-recognition software in much the same way they would a nest of spiders: They recognize, in some abstract way, that it probably has some benefits. But it still gives them the creeps.

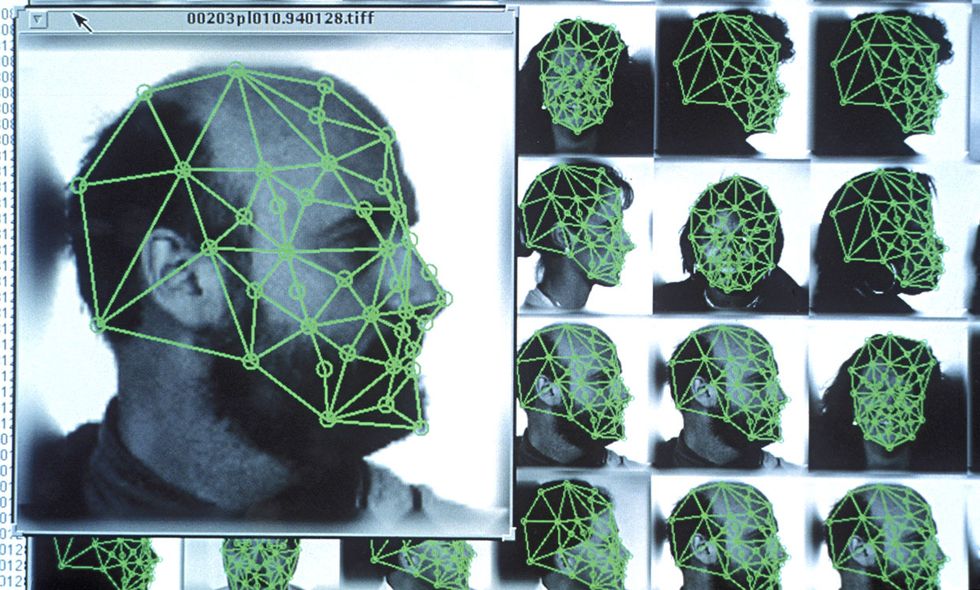

It's time for us to get over this squeamishness and embrace face recognition as the life-enhancing—indeed, life-saving—technology that it is. In many cities, closed-circuit cameras increasingly monitor streets, plazas, and parks around the clock. Meanwhile, the price of recognition software is decreasing, while its capabilities are increasing.

I welcome these trends. I want my 9-year-old daughter tracked while she walks alone to school. I want a face scanner at Starbucks to simply withdraw the payment for my coffee from my checking account. I want to board a plane without fumbling for a boarding pass. Most of all, I want murderers or terrorists recognized as they walk on a city street and before they can cause further mayhem.

I understand the very real threats to our civil liberties. Many of us would probably think twice about showing up at a public demonstration if we knew that the authorities were going to compile a list of everyone who was there. And how about those people who will inevitably just happen to be walking by the demonstration, whose facial images will be therefore captured and whose names will be thus added to the list of demonstrators?

Concerns such as these have recently prompted four U.S. cities, including San Francisco and Oakland, Calif., to outlaw the use of facial-recognition technology within their borders. Politicians, pundits, and major media are playing up how this brave new world of AI facial recognition is going to lead to a police state at best, and a dystopia at worst.

As a candidate for the Republican party nomination for president of the United States, I had to ponder these issues deeply. As a politician, it would have been easy for me to play upon people's fears about facial recognition and declare my opposition to it. But I'm not just a politician. I am also a proud transhumanist. I passionately believe that technology is on the verge of utterly transforming our societies and cultures for the better, and that we should start preparing for that transformation now.

In this context, I note that facial-recognition technology, based on neural networks, is only one of several major tech trends that have for years been wearing away at our privacy. Those of us in developed countries are now living in a world with nearly 24 billion smart devices, which we constantly interact with. Some of them are tracking our consumer preferences, purchases, political contributions, and more.

Our privacy has eroded quite a bit in the past couple of decades. The extent of this erosion was revealed dramatically in a New York Times story published on 18 January. A company called Clearview AI has created a database of some 3 billion facial images culled from public sources such as Facebook. When the company's software is presented with a photo of a person, the chances are very high it can identify the person if he or she is in the database.

And yet, as a society, we seem to be doing fine. Over the last 30 years, technology has broadly improved our sense of freedom and our ability to prosper, and has made the world safer than it's ever been.

Privacy, it turns out, is a largely modern construct. Over the millennia when human beings lived in tribes, clans, villages, fiefdoms, and towns, prevailing notions of privacy were very different from today's. “For all of human history, until the modern era, life was lived more or less publicly, as befits most species on Earth," wrote Jeremy Rifkin, an economic and social theorist, in his book The Zero Marginal Cost Society.

The simple fact is that privacy builds walls around people, companies, and government agencies. Transparency, on the other hand, tears walls down. To some people, facial recognition is Big Brother. To others, it's a guardian angel. Which side you're on probably depends on how much you have to hide.

In the coming years, neural networks will be trained to recognize when a person is having a seizure, when a child or an elderly person is lost in the mall, or when someone is drowning in a community pool. Emergency services will be automatically and instantly notified. In many cases, lives will be saved and catastrophes averted. But it won't happen if we decide to shun recognition technologies.

Perhaps facial recognition's biggest contribution will be in the fight against human trafficking. It is an inexpressible tragedy that countless hundreds of thousands of children are trafficked for sexual abuse every year. And it is part of a larger problem: A couple of years ago, the International Labour Organization estimated that in 2016 there were over 40 million people in the world who had been trafficked and were enduring either slavery or forced marriage.

To combat child sex trafficking, investigators have used facial recognition to identify children pictured in online sex ads. Once a child is identified, law-enforcement authorities have a much better chance of finding and rescuing him or her. Some companies are already successfully implementing software to tackle the issue.

U.S. citizens, perhaps more so than those of other countries, tend to be skeptical of the government's ability to solve problems, and reluctant to trust the government to do the right thing, especially when no one is looking. To them I say, how about two-way transparency? Let's turn the tables and use the tech to keep tabs on government officials. Many police officers are already monitored by body cams while on duty. Why not expand such surveillance to vastly larger numbers of government officials while they are on duty and serving the public? Author David Brin offered a compelling vision of such a society as far back as 1998, in his book The Transparent Society.

Another worry is that facial recognition will be biased. Analyses have indicated that the accuracy of some programs is much worse for minorities, increasing the odds that some of them would be erroneously singled out. I agree that this is a very serious concern; however, more recent studies have confirmed that the bias problem is not inherent in the algorithms. Neural networks are only as good as the data they are trained on, so using more diverse data sets will undoubtedly solve the bias problem. Eventually, recognition software will have far less prejudice than a human being, because people's attitudes are inevitably shaped by their upbringing, culture, religion, and biology. I trust code more than I trust hormones.

Anyone interested in the promise and perils of facial recognition technology need look no further than China. It has some of the most advanced systems in the world and has made aggressive use of them in law enforcement, surveillance, security, and commerce. While China has used the technology to catch criminals and make electronic payments more convenient, it has also pursued some rather disturbing applications.

For example, the government's use of the technology to monitor the Uighur population in Xinjiang province has been criticized as intrusive and repressive. I am also dismayed by China's social credit system, an emerging regime that seeks to summarize a person's morality and integrity as a numerical value. The system makes use of facial recognition to assess credits or demerits based on good or bad behavior in the streets and public venues.

Unsettling as they are, I do not believe that abuses such as these could occur in a free society. Western and other, similar democracies have checks and balances, such as truly independent judiciaries and legislatures, that would block any such systematic repression.

Of course, outside of criminality, no government should seek to control behavior or to discourage dissent or harmless weirdness. The most innovative and productive societies on Earth got the way they are in large measure because they explicitly rejected any such control and repression.

One last significant issue on AI facial recognition is the private use of it, which worries some people even more than government use. Companies are already starting to use facial recognition for security reasons in sports stadiums, transportation terminals, office buildings, and hotels. This isn't much different than closed-circuit TV, which many public and private areas already have and which has proven useful in increasing public safety.

But the equation changes when people believe companies are monitoring them for commercial purposes. Might Walmart facial recognition follow us into their stores and determine that we buy an awful lot of vodka? Many people don't want to be fodder for a data-mining scheme, even if it increases their safety.

Personally, I don't mind any of this. But for those who do, companies in the future could just give us a choice to stop all facial recognition when we enter their stores or private areas. Maybe they'll have an app that lets us easily opt out, like the unsubscribe links at the bottom of most targeted emails.

Actually, as far as the commercial sector goes, I see no reason to fear facial recognition run amok. Inevitably, people who want to protect themselves from being recognized will find ways to do that, and some of them will even get rich selling products offering such protection. That's capitalism at its finest.

We can argue about the promise and perils of facial recognition technology as long as we like, but it's pretty clear now that there will be no stopping it. The attractions for government agencies, commercial enterprises, and even individuals are simply too great. Do you unlock your phone with your face? Do you like having the ability to search your online photo libraries for a specific person? There are many millions of people who do. While enjoying such uses, we'll tolerate the others, in much the same way that we like the convenience of email and tolerate the endless spam that goes with it.

The road to ubiquitous facial recognition won't be smooth or straight. There will be pitfalls and unforeseen twists. But overall, it will make daily life more functional and will help keep us all safer. Rather than fighting and complaining about it, we ought to embrace its promise and be wary and vigilant enough to ensure that its global rollout is sensible, unbiased, and as beneficial as possible for all.

About the Author

Zoltan Istvan is a Republican candidate for U.S. president in 2020. His sci-fi novel The Transhumanist Wager (2013, Futurity Imagine Media) is taught in futurist studies around the world, and he is the subject of the new documentary Immortality or Bust.