Electronics that self-destruct over time could be the key to military applications to help keep secrets out of enemy hands, medical implants that don't need surgical removal, and environmental sensors that melt away when no longer needed. Now scientists at Iowa State University say they have developed the first practical transient battery to power them.

Recently, scientists have developed a wide range of transient electronics that can perform a variety of functions until exposure to light, heat, or liquids triggers their self-destruction. Until now, however, these devices largely relied on external power sources that were not transient themselves.

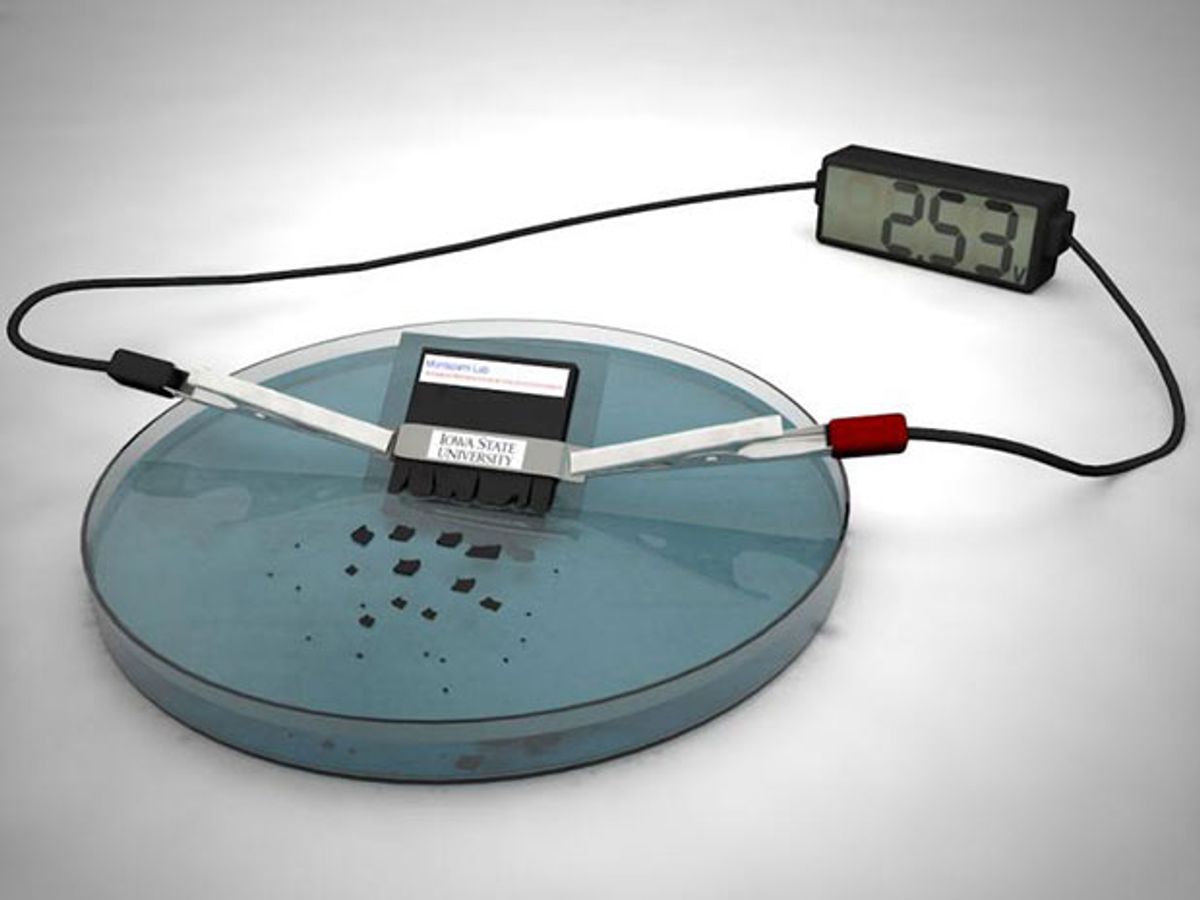

Early research into transient batteries led to devices with limited power, stability, and shelf life. They were also slow to destroy themselves, says Reza Montazami, a materials scientist at Iowa State University who led the effort to invent a better transient battery. Now Montazami and his colleagues have developed a transient battery that can power a desktop calculator for about 15 minutes and destroy itself in about 30 minutes.

To generate practical levels of electricity, the scientists relied on the lithium-ion chemistry found in many commercial batteries. Nanoparticles and microparticles of lithium salts and silver made up the battery's active components, which the researchers encased in a degradable polymer. Altogether, the battery was about 1 millimeter thick, 5 mm long, and 6 mm wide.

The battery can deliver more than 2.5 volts, twice as high as other transient batteries. It also destroys itself roughly 1,000 times faster than previously reported self-destructing batteries.

When submerged in water, the battery's polymer casing swells, breaks up, and dissolves away. The battery's active components are not soluble in water, but the nano- and micro-sized nature of these particles helps them easily disperse. "The particles are hardly traceable," Montazami says.

The scientists are now exploring the mechanics of dissolution in greater detail to "help us design more controllable systems," Montazami says.

The scientists detailed their findings recently in theJournal of Polymer Science, Part B: Polymer Physics.

Charles Q. Choi is a science reporter who contributes regularly to IEEE Spectrum. He has written for Scientific American, The New York Times, Wired, and Science, among others.