Late last week, the U.S. House of Representatives passed legislation to mandate federal research on a radically ‘retro’ approach to protect power grids from cyber attack: unplugging or otherwise isolating the most critical equipment from grid operators’ digital control systems. Angus King, an independent senator from Maine whose identical bill passed the Senate last month, says such a managed retreat from networked controls may be required to thwart the grid’s most sophisticated online adversaries.

Grid cyber experts say the Securing Energy Infrastructure Act moving through Congress is a particular testament to Michael Assante, a gifted and passionate cybersecurity expert who died earlier this month from leukaemia at the age of 48. “If you were to point to just one person as the primary driver, it would have to be Michael,” says colleague Andrew Bochman, senior cyber and energy security strategist at Idaho National Laboratory (INL). Senator King recently told The Washington Post that research at INL kicked-off by Assante had inspired the bill.

Assante trained in cyberdefense as a naval intelligence officer and then joined the power industry in 2002 as chief security officer (CSO) for U.S. electricity giant American Electric Power. Encountering skepticism about the grid’s cyber vulnerability, Assante moved to INL in 2005 to prove the case. There he led the infamous Aurora Generator Test. The video below captures its dramatic results.

Parts fly and smoke billows as fluctuating relay settings quickly throw a generator’s spinning rotor out of sync with the grid’s alternating current. The US $2 million test was the first demonstration that remote signals could destroy an industrial machine, and it turned a lot of heads.

Since the Aurora test, the power industry has boosted its investment in cybersecurity, focusing largely on software and hardware upgrades to make networks harder to penetrate. But many top cyber security experts tracking increasing intrusions into grid control systems have concluded that such ’cyber hygiene’ could not prevent damaging attacks.

In 2015, Assante and two coauthors issued an impassioned call for a new approach: isolating critical equipment from the grid’s increasingly complex control networks. “We must prepare for adversaries equipped to gain access to our most critical systems,” wrote Assante and his coauthors—Bochman at INL and Tim Roxey at the North American Electric Reliability Corporation or NERC, the industry’s grid safety organization.

The trio’s appeal gained extra punch when, two months after its release, blackouts hit Ukraine—the first to be definitively traced to a cyber intrusion. “It was almost prophetic,” recalls Chris Sistrunk, principal industrial control system consultant for Mandiant Consulting, an arm of cybersecurity firm FireEye.

The blackouts, traced to a Russian team, were short-lived thanks to the grid’s relatively shallow level of digital automation. Ukraine’s grid operator was able to quickly bypass its compromised controls by dispatching engineers to substations to actuate manual switches. They brought most affected regions back online within just six hours.

Strengthening manual backup systems is one of several protection strategies covered by the legislation moving through Congress, which mandates research by the U.S. Department of Energy. Another is keeping some equipment under manual control full-time, therefore preventing attacks via compromised control systems. A third is opting out of some digital controls from the start. (Digital upgrades are just gathering steam at nuclear power plants, most of which still use harder-to-hack analog controls.)

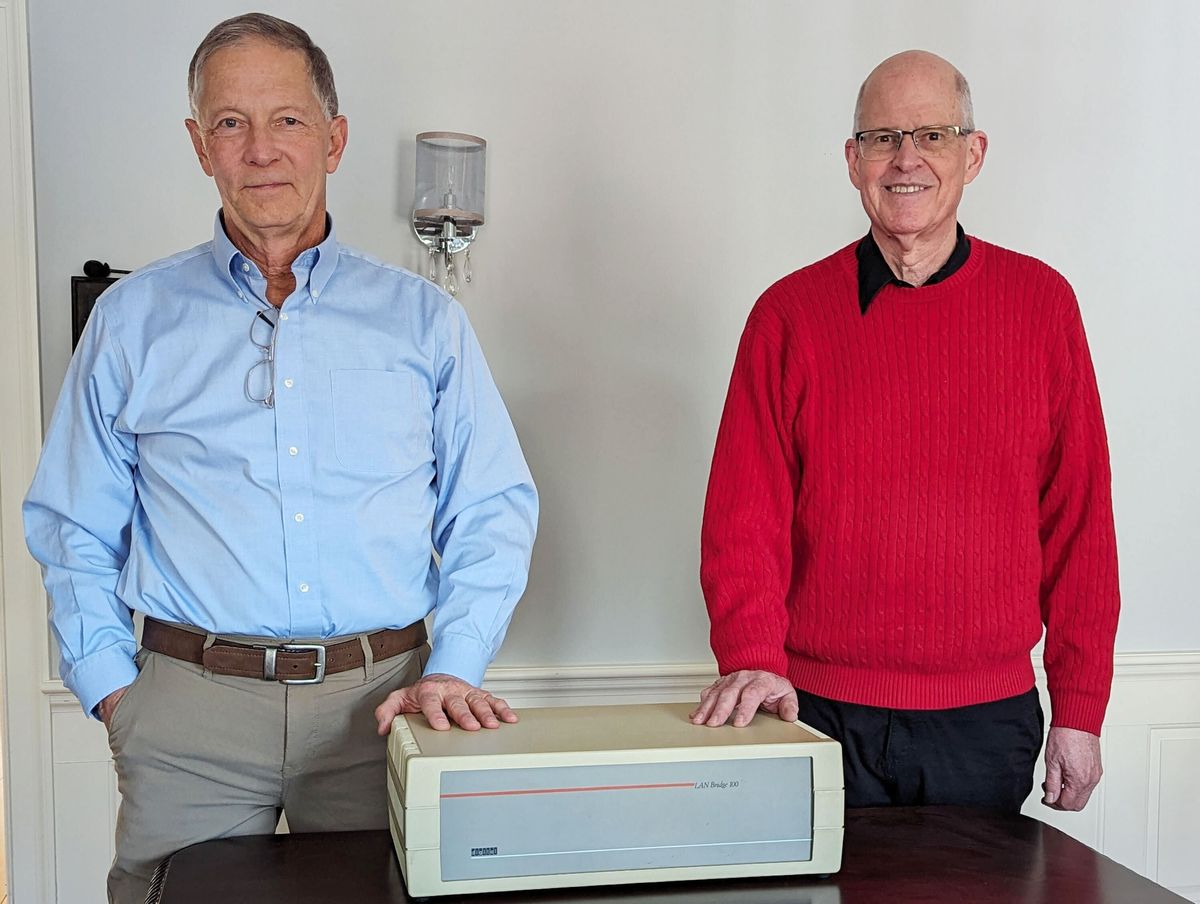

Roxey, now retired from NERC, is developing a fourth approach: adding simple, dedicated control boxes that prevent specific cyberattacks. His prototype, a failsafe against the Aurora test scenario, sits between a grid’s control system and the switches that regulate power flow to a rotating machine.

Consider the big pumps that deliver drinking water to cities, whose destruction could put large populations at risk for weeks or months. The simple circuit within Roxey’s “attack surface disruptor” monitors the grid’s alternating current and blocks switching commands from the relay that would place the pump out of sync.

The key, says Roxey, is that his device cannot be reprogrammed, and has no network connection. “This thing is not computerized. You have to physically walk up to the device and put your hands on it if you want to manipulate it,” he says.

Bochman says the efforts by Roxey, INL, and other groups to simplify and isolate the cybersecurity toolbox have received limited support to date. That’s not surprising, he says, since they go against the grain, questioning the seemingly inexorable movement toward more complicated digital controls and digital defenses.

The research mandated by the Securing Energy Infrastructure Act will help, says Bochman. But the legislation is not quite ready to go to the White House. It’s attached to an intelligence bill whose differing versions must now be reconciled by the House and Senate.

Peter Fairley has been tracking energy technologies and their environmental implications globally for over two decades, charting engineering and policy innovations that could slash dependence on fossil fuels and the political forces fighting them. He has been a Contributing Editor with IEEE Spectrum since 2003.