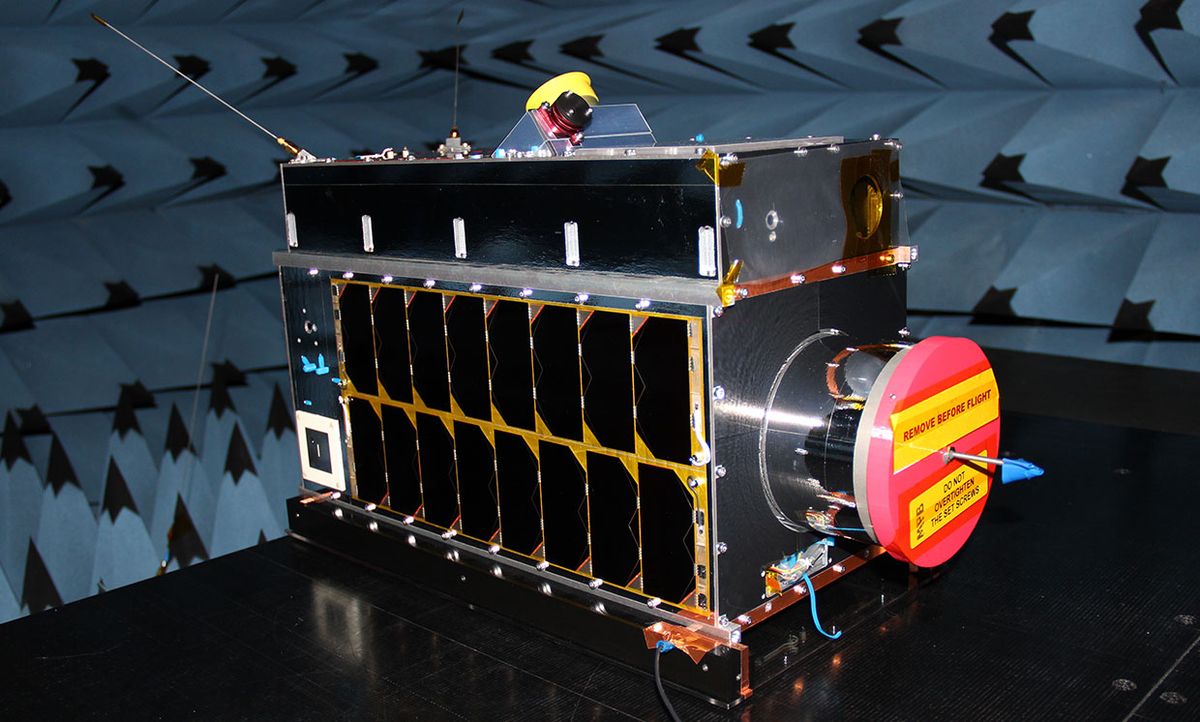

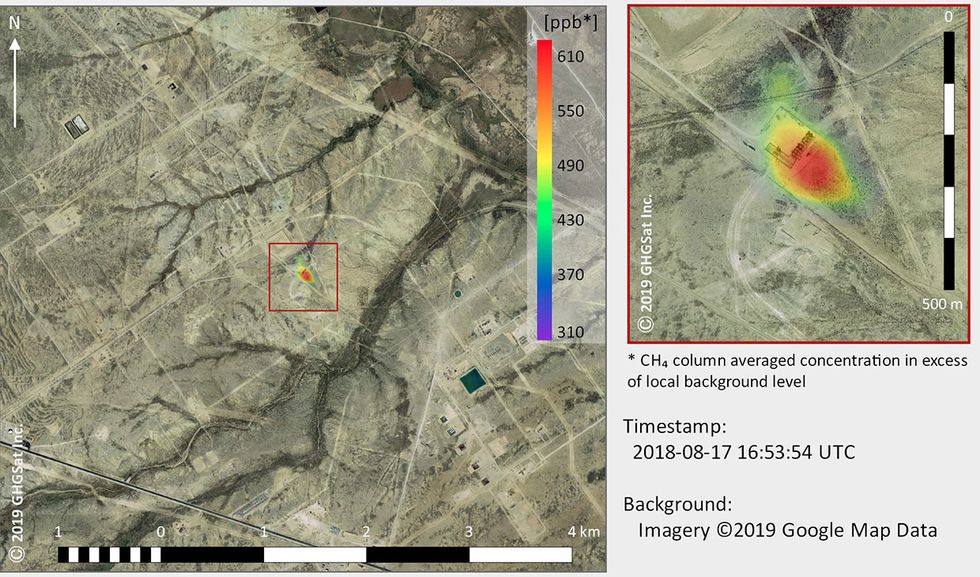

Claire, a microsatellite, was monitoring a mud volcano in Central Asia when a mysterious plume appeared in its peripheral view. The 15-kilogram spacecraft had spotted a massive leak of methane—a powerful climate pollutant—erupting from an oil and gas facility in western Turkmenistan. The sighting in January 2019 eventually spurred the operator to fix its equipment, plugging one of the world’s largest reported methane leaks to date.

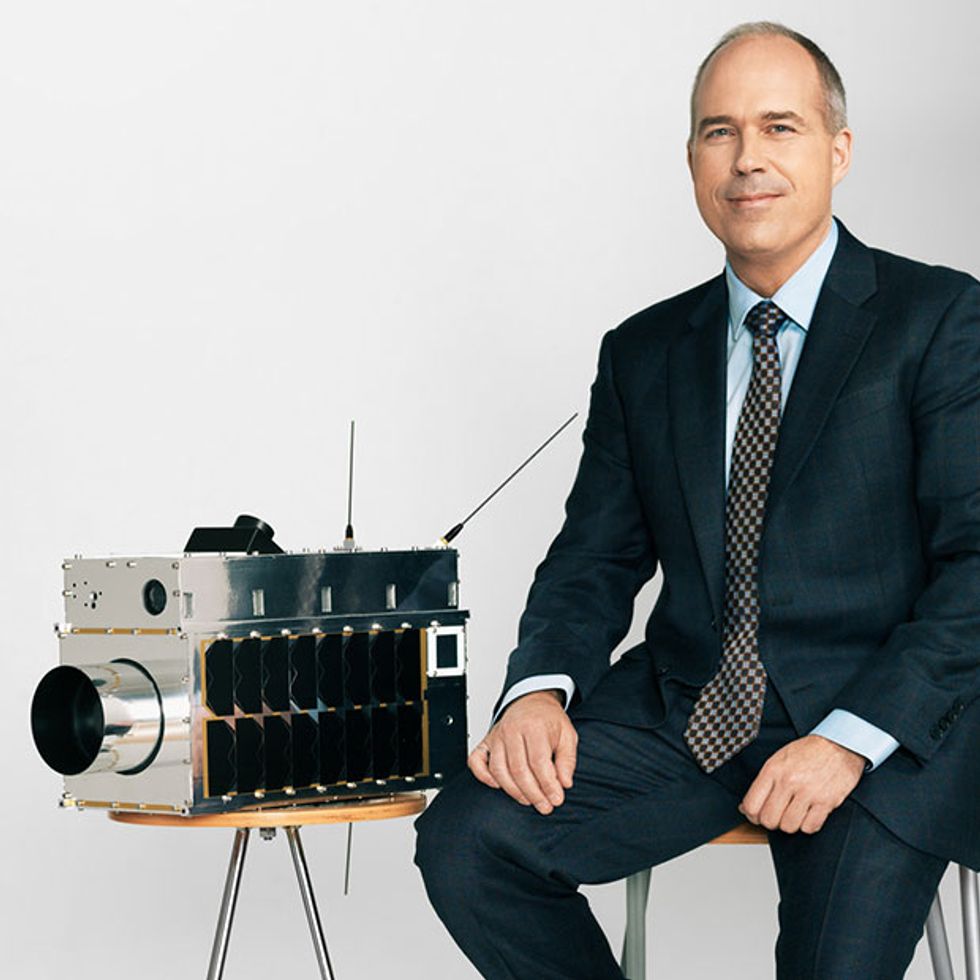

Canadian startup GHGSat launched Claire four years ago to begin tracking greenhouse gas emissions. Now the company is ready to send its second satellite into orbit. On 20 June, the next-generation Iris satellite is expected to hitch a ride on Arianespace’s Vega 16 rocket from a site in French Guiana. The launch follows back-to-back delays due to a rocket failure last year and the COVID-19 outbreak.

GHGSat is part of a larger global effort by startups, energy companies, and environmental groups to develop new technologies for spotting and quantifying methane emissions.

Although the phrase “greenhouse gas emissions” is almost synonymous with carbon dioxide, it refers to a collection of gases, including methane. Methane traps significantly more heat in the atmosphere than carbon dioxide, and it’s responsible for about one-fourth of total atmospheric warming to date. While mud volcanoes, bogs, and permafrost are natural methane emitters, a rising share is linked to human activities, including cattle operations, landfills, and the production, storage, and transportation of natural gas. In February, a scientific study found that human-caused methane emissions might be 25 to 40 percent higher than previously estimated.

Iris’s launch also comes as the Trump administration works to ease regulations on U.S. fossil fuel companies. The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency in May sought to expedite a rollback of federal methane rules on oil and gas sites. The move could lead to an extra 5 million tons of methane emissions every year, according to the Environmental Defense Fund.

Stéphane Germain, president of Montreal-based GHGSat, said the much-improved Iris satellite will enhance the startup’s ability to document methane in North America and beyond.

“We’re expecting 10 times the performance relative to Claire, in terms of detection,” he said ahead of the planned launch date.

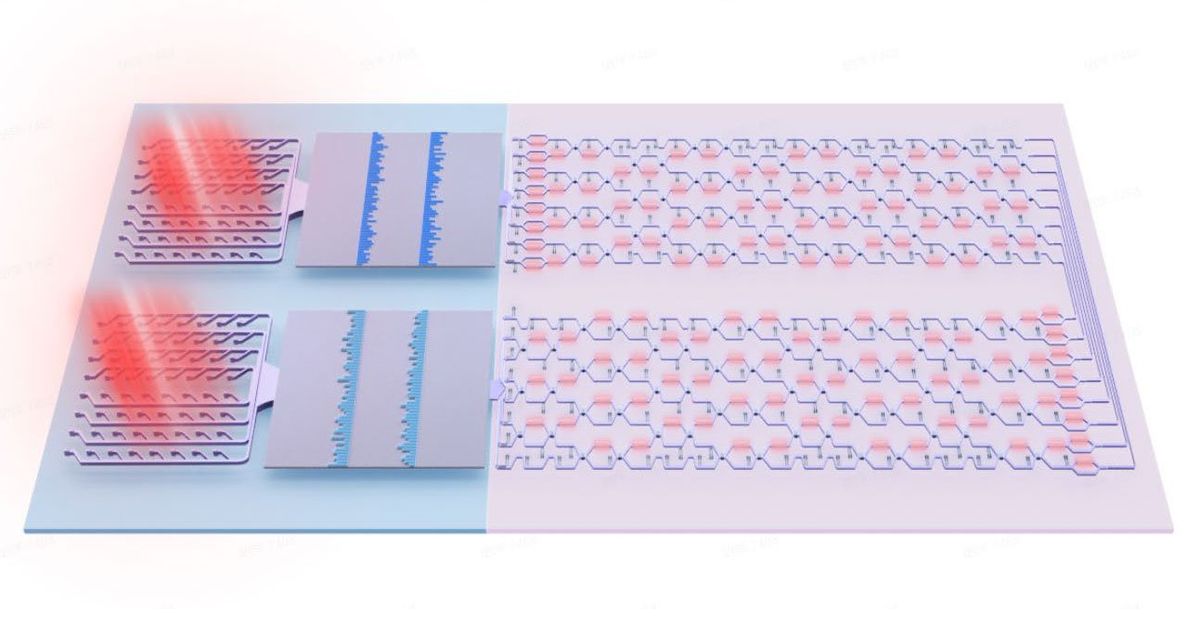

The older satellite is designed to spot light absorption patterns for both carbon dioxide and methane. But, as Germain explained, the broader spectral detection range requires some compromise on the precision and quality of measurements. Iris’s spectrometer, by contrast, is optimized for only methane plumes, which allows it to spot smaller emission sources in fewer measurements.

Claire also collects about 25 percent of the stray light from outside its field of view, which impinges on its detector. It also experiences “ghosting,” or the internal light reflections within the camera and lens that lead to spots or mirror images. And space radiation has caused more damage to the microsat’s detector than developers initially expected.

With Iris, GHGSat has tweaked the optical equipment and added radiation shielding to minimize such issues on the new satellite, Germain said.

Other technology upgrades include a calibration feature that corrects for any dead or defective pixels that might mar the observational data. Iris will test an experimental computing system with 10 times the memory and four times the processing power of Claire. The new satellite will also test optical communications downlink, allowing the satellite to bypass shared radio frequencies. The laser-based, 1-gigabit-per-second downlink promises to be more than a thousand times faster than current radio transmission.

GHGSat is one of several ventures aiming to monitor methane from orbit. Silicon Valley startup Bluefield Technologies plans to launch a backpack-sized microsatellite in 2020, following a high-altitude balloon test of its methane sensors at nearly 31,000 meters. MethaneSAT, an independent subsidiary of the Environmental Defense Fund, expects to complete its satellite by 2022.

The satellites could become a “big game changer” for methane-monitoring, said Arvind Ravikumar, an assistant professor of energy engineering at the Harrisburg University of Science and Technology in Pennsylvania.

“The advantage of something like satellites is that it can be done remotely,” he said. “You don’t need to go and ask permission from an operator — you can just ask a satellite to point to a site and see what its emissions are. We’re not relying on the industry to report what their emissions are.”

Such transparency “puts a lot of public pressure on companies that are not managing their methane emissions well,” he added.

Ravikumar recently participated in two research initiatives to test methane-monitoring equipment on trucks, drones, and airplanes. The Mobile Monitoring Challenge, led by Stanford University’s Natural Gas Initiative and the Environmental Defense Fund, studied 10 technologies at controlled test sites in Colorado and California. The Alberta Methane Field Challenge, an industry-backed effort, studied similar equipment at active oil-and-gas production sites in Alberta, Canada.

Both studies suggest that a combination of technologies is needed to effectively identify leaks from wellheads, pipelines, tanks, and other equipment. A plane can quickly spot methane plumes during a flyover, but more precise equipment, such as a handheld optical-gas-imaging camera, might be necessary to further clarify the data.

GHGSat’s technology could play a similarly complementary role with government-led research missions, Germain said.

Climate-monitoring satellites run by space agencies tend to have “very coarse resolutions, because they’re designed to monitor the whole planet all the time to inform climate change models. Whereas ours are designed to monitor individual facilities,” he said. The larger satellites can spot large leaks faster, while Iris or Claire could help pinpoint the exact point source.

After Iris, GHGSat plans to launch a third satellite in December, and it’s working to add an additional eight spacecraft — the first in a “constellation” of pollution-monitoring satellites. “The goal ultimately is to track every single source of carbon dioxide and methane in the world, routinely,” Germaine said.