Thirst For Power

Can thousands of small dams solve Africa's power crunch?

In the gorgeous Ruwenzori mountains of western Uganda, on a ridge above a fast-moving creek, a young man leans against a mango tree, a machete dangling from his arm. It is his job to guard one of the funkiest, tiniest dams in the world.

It’s a hunk of concrete, about four meters across, that interrupts a natural waterfall, diverting water into a large reservoir. That pool drains into a rusted steel pipe that runs along the creek and then drops sharply into a white stucco-covered bungalow the size of a walk-in closet. Inside the bungalow, a turbine generator capable of producing 60 kilowatts churns out electricity, which is carried via underground wires to the Kagando Christian Hospital, 3 kilometers away.

The zany contraption is the hospital’s chief source of electricity, and it is incredibly reliable—five years have gone by since a turbine blade needed replacing. The entire system cost less than US $15 000.

At a state-of-the-art hospital, 60 kilowatts would just barely keep an MRI facility going, but here in this rural corner of East Africa, it’s enough to keep 100 nurses and doctors, and hundreds more patients, bathed in light, and to power their dental, surgical, and lab equipment, as well as their kitchen and laundry.

That explains the presence of the man with the machete: he works for the hospital, and he is protecting the dam from vandals. The little hydro facility has brought life and some semblance of order to a place where politics and official infrastructure have generally meant failure and disappointment.

“The government has promised and promised to bring electricity to this village and never has,” says Sabuni Seezi, who maintains the hospital’s microhydro. “So we did it ourselves.”

And what works for Uganda has enormous promise all over sub-Saharan Africa, the most energy-poor region in the world. Excluding highly developed South Africa, the region has only about 30 gigawatts of installed capacity, about the same amount as Poland. But to spread the benefits of microhydro would take a seismic shift in the continent’s usual electrification paradigms and—perhaps more ambitiously—a renunciation of the crippling mix of politics and patronage that have left the continent with some of the worst electrification rates in the world. And nowhere are the tensions over microhydro more apparent than in Uganda, with its many rivers, including the Nile. Here, the struggle to balance the potential for both large and small hydroelectric projects has already begun.

Big dams still dominate Africa’s electricity scene. They have been at the center of infrastructure development on the continent for 50 years, ever since Egypt built the 2.1-gigawatt Aswan Dam on the Nile and Ghana built the 768-megawatt Akosombo Dam on the Volta River. Now in addition to its main dam on the Nile at Owen Falls near Jinja, the Ugandan government is planning to build two more large dams on different points of the Nile at an estimated cost of $750 million. The larger and more expensive, at Bujagali, was put on hold in 2002 and is now being revived.

Uganda is not alone among African countries in its reliance on big hydro; nine others receive at least 80 percent of their electricity from hydro, including Cameroon, Ethiopia, Ghana, Mozambique, and Zambia. Hydro contributes more than 60 percent of the electricity in Angola, Benin, Kenya, Namibia, Rwanda, Sudan, and Tanzania.

Because large dams are so expensive, they carry great risks, especially in drought-prone areas, and require capable management by government. Microhydro systems such as the one at the Kagando hospital are appealing because they cost less, reach places far outside the national grid, and give local communities a direct stake in their power systems. They also don’t require the involvement of national government agencies—which, in Africa, are often corrupt, incompetent, or both.

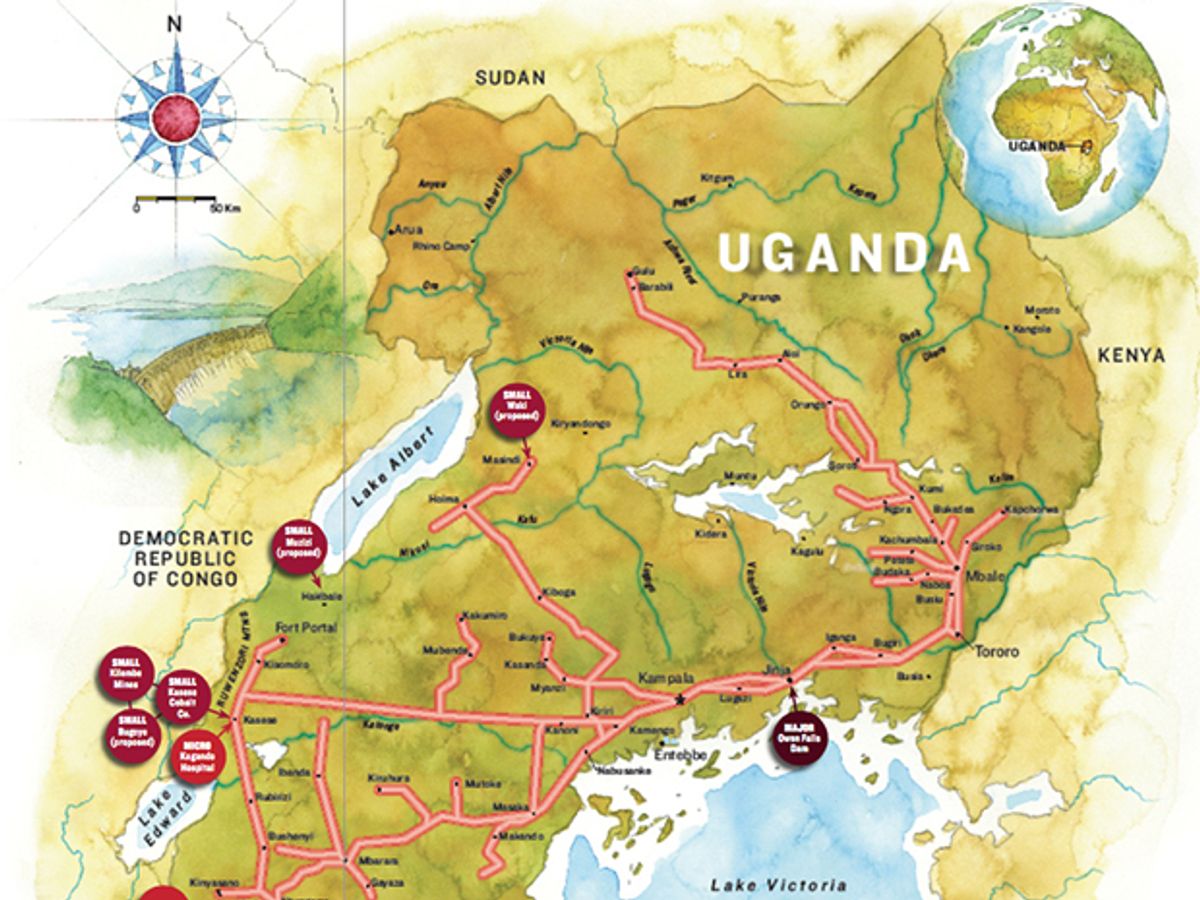

According to the Uganda Ministry of Energy, the country has three working microhydros, and a dozen more are in various stages of planning. “These microhydros are worth building in large numbers,” says Philippe Simonis, a German energy expert who works for the Ugandan government. He has advised the government to consider a crash program to spread microhydro projects all over the country. “It is possible to have hundreds, even thousands of them in Uganda alone, and tens of thousands around Africa” he says.

Uganda’s main dam at Owen Falls is rated at 200 MW. Even in the best of times, the dam supplies electricity to just 5 percent of Uganda’s 28 million people. And these are hardly the best of times. Because of a drought in East Africa, the dam is producing half its normal output, blacking out huge swaths of Uganda’s neighborhoods and industrial centers.

Nevertheless, large dams continue to dominate government agendas, not only in Uganda but throughout sub-Saharan Africa. Paul Mobiru, senior energy adviser to Uganda’s president, Yoweri Museveni, says the dams are grabbing most of the public money available for electricity development [see map, “Africa’s Big Dam Projects”. That’s a shame, many analysts say. The emphasis on large dams reinforces centralized power and invites corruption, because large dams bring big money into the hands of a few government officials and technocrats. By contrast, small dams capable of generating up to 15 MW are relatively inexpensive and require the hands-on involvement of villages and communities, thus potentially serving as a tool for local empowerment. Perhaps because small dams spread political and economic power, rather than concentrate it, African governments and the foreign donors who fund so much of Africa’s infrastructure have generally ignored them.

Microhydro systems produce up to 100 kW of power and usually cost $200 to $500 per kilowatt of capacity to install. In a typical project, most of the expenditures go toward construction of channels, dams, and distribution networks as well as turbines and other basic equipment.

One of the great advantages of microhydros is that they can electrify remote communities far from the grid relatively quickly and economically. That’s a huge potential benefit, because today in Africa the grid typically reaches less than 10 percent of the population. Half of black Africa’s population will still be living without grid-supplied electricity some 25 years from now, according to a United Nations forecast. Many African countries are so large that plans to extend the grid beyond major cities might remain too costly for generations.

Microhydros are already popular in Vietnam and China. In China alone, an estimated 42 200 microhydros provide some 28 GW, according to the Chinese government.

In Africa, the first microhydros were built in the 1920s by European settlers. The oldest system in Malawi, for instance, powers a tea-processing factory in the foothills of the spectacular Mulanje Mountains, a major destination for tourists to southern Africa. The Mulanje microhydro has been running continuously for nearly 80 years, using the three original impulse turbines, which combined are capable of producing 600 kW. “Our maintenance has actually been nearly zero for a decade,” says Jim Melrose, managing director of Lujeri Tea Estates, Malawi’s second-largest tea producer. And yet, oddly enough, the tea company is said to be the only enterprise in Malawi that relies on microhydro technology.

Melrose is contemplating building a second microhydro to power sprinkler heads and water pumps in new tea fields. “I feel like we’re moving back to the future,” he says. “We’re embracing a forgotten technology that has obvious economic advantages today.”

“There’s no way we can depend on the government or a big electricity company to satisfy our needs. Microhydro lets us control our own destiny.”

As he speaks, Melrose is surveying a river that runs through his estate. He is assessing its suitability for powering his second microhydro installation. The ideal site is on a fast-moving stream or creek where the water runs year-round, without major seasonal fluctuations in flow. The simplest design is a run-of-river system, whereby water courses into a small dam, called a weir, that diverts the flow into a channel and then into a pipe, which feeds a turbine.

The electricity potential of the system depends on the flow of the river and the angle and length of the vertical drop from the weir. As a general rule, there are 9.8 kW available from each cubic meter per second of water falling through 1 meter. The greater the drop, or "head," the lesser the flow of water required to achieve the same electricity. So to compute the electrical output, you need to know the head, the flow rate of the water, and the turbine’s efficiency.

Turbines used in microhydro dams are generally of the impulse type, in which nozzles focus the incoming water on the curved blades of the turbine. The water jet imparts kinetic energy to the blades, which spin, turning the rotor of the attached generator to produce electricity. Impulse turbines don’t require housing—which makes them easy to maintain and build. They are also relatively tolerant of sand and grit.

Amateurs can construct simple microhydros. Parts can even be homemade. Jimmy Omona, a turbine maker in Jinja, constructs basic turbines for microhydro systems from sheet metal, bearings, nylon rods, and pipe. “The blades can be created simply, even by slicing a standard pipe in quarters,” Omona says.

Small hydro installations , which include systems that can generate anywhere from 1 MW up to 15 MW of power, tend to be more technologically sophisticated than microhydro systems and have the potential to feed into a grid. In western Uganda, about an hour’s drive from the Kagando hospital, a small hydro electrifies an enterprise that extracts valuable cobalt from the tailings left by a shuttered copper mine.

“Without our own power station, we cannot function,” says Rob Jennings, general manager of the Kasese Cobalt Co. The entire system cost $25 million to build six years ago and boasts such amenities as bridges that let farmers and their goats cross the canal at 14 different points.

Drawing on water from the Mubuku River, the Kasese system is beautiful as well as effective. It has an installed capacity of 9 MW from three identical German-made turbines that are fed by water running along several miles of a concrete-lined canal that angles down through the verdant Ruwenzori foothills. The canal culminates in a mile-long underground channel that turns into a head pond. There the water is trapped and forced into a 1.8-meter pipe, dropping 610 meters to the computer-controlled turbines located along the Mubuku.

The water is shifted from the single pipe to six branch pipes, two for each of the three reaction turbines, which are commonly used in large hydro plants. The specific kind of reaction turbines operating at Kasese are Francis turbines, named for James B. Francis, who invented them in the 1840s. Francis turbines are efficient but expensive to maintain. Unlike an impulse turbine, a reaction turbine needs housing to contain the water flow. And instead of nozzles focusing the water on the blades, a spiral-shaped inlet directs water onto the rotor blades. Water changes pressure and gives up its energy as it moves down through the turbine.

Maintaining the Kasese hydroelectricity station requires constant vigilance. One recent morning, Paul Kasaija drove a Toyota pickup truck on a dirt road along the canal, passing horned cattle on his right and banana groves on his left. A graduate of a Ugandan technical college, Kasaija first checked the head pond, rimmed by barbed wire, then spot-checked workers clearing debris from metal gratings, or “grave exits,” designed to prevent the main pipe leading to the turbines from getting clogged. Each Friday, Kasaija measures outflow into drainage pipes and studies the water loss due to leaks in the concrete-lined canals. “The less water," he notes, "the less electricity.”

Most days, the Kasese operation satisfies its own power needs, and even sells electricity to the national grid, which is always hungry for power. In fact, potential revenues from sales to the national grid have prompted a $100 million investment from the Norwegian company SN Power, which has begun work on two small hydro projects in the north of Uganda and two more in the west.

On a sunny, breezy day , Charles Musekura steps into a creek near Kasese, about 10 kilometers south of the cobalt plant. He’s getting his feet wet, literally, in order to feel the speed of the water in the creek, as it pours over a 2.5-meter-wide fall.

“I am suffering without enough electricity,” Musekura says. He runs a limestone plant that relies on heavy machinery. With the national grid usually turning off power to Kasese every other day, he must improvise. Instead of running a rock-crushing machine, he hires men to bake in the hot sun, pulverizing rocks with sledgehammers. The men earn a dollar a day. “I can’t wait for a big dam to get built,” Musekura says. “I need electricity now.”

Yet Musekura is reluctant to stump for small hydro systems, fearful of drawing the ire of the Ugandan government, which behaves as if support for cheap microhydros will undermine willingness to build big dams.

In power for more than 20 years, President Museveni remains outraged over the failure of his government to build the large Bujagali dam 10 years ago. The project was terminated in 2002 amid complaints that it didn’t make economic sense. The financing fell through, and the company that was to have built the dam, AES Corp. of Arlington, Va., backed out.

Museveni blames the failure on environmentalists who opposed the project on both economic and technical grounds. Early last year, after the onset of crippling electricity shortages, Museveni promised to build two new large dams on the Nile, and he lashed out at foreign environmentalists, calling them "confused groups...who make it their business to manage African countries."

Environmentalists reject Museveni’s charges. “We actually predicted these electricity shortages and have long urged President Museveni to diversify the country’s energy sources,” says Patrick McCully, executive director of the International Rivers Network, an advocacy group in Berkeley, Calif., that generally opposes large dams. In Uganda, meanwhile, environmentalists are countering the official support for large dams by pushing for other energy options, including small hydros and microhydros.

On a recent afternoon, Frank Muramuzi, a leading Ugandan environmentalist and a critic of Museveni’s big-dam strategy, drove past dozens of wood- burning kilns on the roadside. Men were baking bricks for the construction of houses. The smoke was thick and acrid.

“This is what we are fighting,” Muramuzi says. Clean hydropower must replace wood burning, he maintains, or the country’s tree cover, already diminished, will be destroyed.

After about an hour, Muramuzi veered off the main, paved road. He went up a hill and found one of the villages closest to the government’s favored Bujagali big-dam project. About 50 people had gathered outside the house of a local “big man.” The men were seated in chairs on one side, and women were on the ground on the other. Muramuzi addressed the villagers in the dominant local language, Luganda. “Small hydros are cheaper,” he told the group. “And if you get a bad event—say, the river dries up—you can remove it.”

Muramuzi says he isn’t against large dams but wants the government to consider a wider range of options, including small hydro systems. He relishes the chance to speak with villagers, who are so often ignored by politicians and planners and yet lack the initiative to mount their own energy projects. “I am feeling you in my heart whenever I come here,” he told them that day. “I feel I don’t want to go back to Kampala,” the Ugandan capital.

But return he does, because it is in Kampala where the battles are fought. A week later he is sitting in an air-conditioned conference room at the Ministry of Energy and Mineral Development, across a conference table from the government’s chief energy adviser, Paul Mobiru. The two men, sipping tea and munching on biscuits, have clashed in the past. But today Mobiru is conciliatory. “Small hydro projects have a very big role to play,” he tells the activist. “We see a huge role for them, especially in rural areas.” He cites new interest by the country’s rural electricity agency to fund small hydro projects. Even so, there is no formal program to support small hydro, only ad hoc offers of assistance in response to interest from individuals.

Mobiru insists that small-scale hydros are only “a supplement” and that the government must also sponsor large hydros and the big dams that support them. Muramuzi nods his head, happy to hear the endorsement of small hydros and wary of pushing his opposition to large dams too strongly. “If you push too hard,” he says later, “you’ll have the people in power running from you, and the whole process will collapse. We want a voice at the table, and for that we must handle the government officials with care.”

It’s a reminder that the electricity issue in Africa, as elsewhere, is as much political as it is technical. Big dams are prestige projects, symbols of national power that drive employment and industry. Small hydros, dispersed and difficult for the government to keep track of, let alone manage, seem vaguely subversive.

But hundreds of miles away from that air-conditioned conference room, the argument over large versus small hydros is purely academic. The onset of the dry season means less electricity for the hospital in Kagando.

Because of the lower water levels that accompany the dry season, hydroelectric power gets exhausted most days, and the hospital usually lacks the money to pay for the diesel fuel that feeds a backup generator. To help squeeze as many kilowatts as possible from the systems, Sabuni Seezi, who keeps the microhydro system going, clears debris from the small reservoir that flows into the pipe leading to the turbine. Even so, during the dry season, which continues until about November, power runs out during the day, and surgeons and other specialists stop their work, waiting for their microhydro to catch up with their needs.

Spreading out the medical work isn’t an option in the maternity ward, however, where electricity or not, babies come into the world. Later in the same day that Seezi clears reservoir debris, a dozen women, in various stages of labor, steady themselves as the sun sets. Relatives, who camp outside on the perimeter of the maternity ward, bring out candles that fit neatly in locally made clay holders sold for a pittance by peddlers. Aided by the modest lights, nurses and doctors do their best, waiting for the electricity to come back on again.

About the Author

G. PASCAL ZACHARY teaches journalism at Stanford University and writes often about African affairs for newspapers and magazines. He is the author of three books, most recently The Diversity Advantage: Multicultural Identity in the New World Economy. His writings on Africa are available at https://africaworksgpz.com.

To Probe Further

For a solid introduction to microhydro, see the British group Practical Action’s site: https://practicalaction.org/?id=micro_hydro_expertise.