Statistics on the production of energy are fairly reliable; accurate statistics on the consumption of energy by major sectors are harder to come by; and data on the energy consumed in the production of specific goods are even less reliable. Such energy embodied in products is part of the environmental price we pay for everything we own and use.

The estimation of the embodied energy of finished goods relies not only on indisputable facts—so much steel in a car, so many microchips in a computer—but also on the inevitable simplifications and assumptions that must be made to derive overall rates. Which model of car? Which computer or phone? The challenge is to select reasonable, representative rates; the reward is to get a new perspective on the man-made world.

Let’s focus on mobile devices and cars. Mobile devices, because they are the primary enablers of instant communication and boundless information; cars, because people still want to move in the real world.

Obviously, a car weighing 1.4 metric tons (about as much as a Honda Accord LX) embodies more energy than the 140 grams of a smartphone (say, a Samsung Galaxy). But the energy gap is nowhere near so great as that 10,000-fold difference in mass.

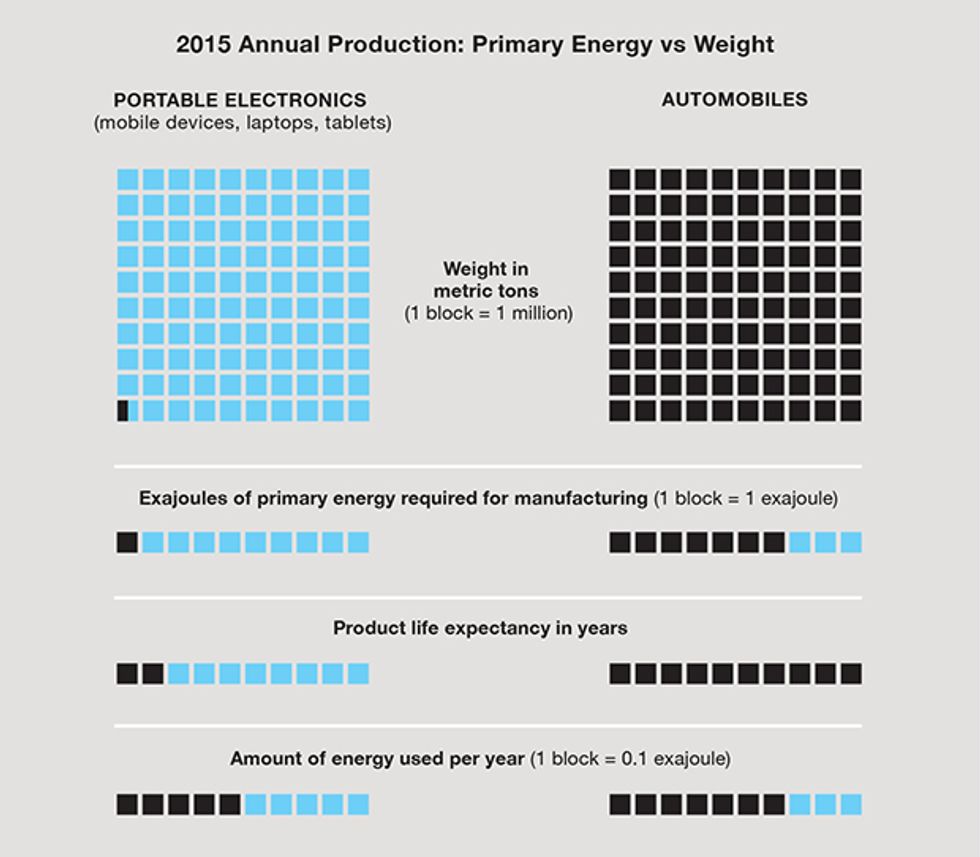

In 2015, worldwide sales of mobile phones reached about 1.9 billion, those of laptops amounted to about 60 million, and tablet sales surpassed 230 million. The aggregate weight of these devices came to about 550,000 metric tons. Assuming, conservatively, an average embodied rate of 0.25 gigajoules per phone, 4.5 GJ per laptop, and 1 GJ for a tablet, the annual production of these devices required about 1 exajoule (EJ, 1018 J) of primary energy. With about 100 GJ per vehicle, the 72 million vehicles sold in 2015 embodied about 7 EJ of energy and weighed about 100 million metric tons. New cars thus weighed more than 180 times as much as all portable electronics, but required only seven times as much energy to make.

And as surprising as that may be, we can make an even more startling comparison. Portable electronics don’t last long—on the average just two years—and so the world’s annual production of these products embodies about 0.5 EJ per year of use. Because passenger cars typically last for at least a decade, the world’s annual production embodies about 0.7 EJ per year of use—which is only 40 percent more! This means that even if the roughly calculated aggregates err in opposite directions (so that cars embody more energy and electronics less) the global totals would still be not only of the same order of magnitude but most likely within a factor of two.

Of course, operating energy costs are vastly different. A compact American passenger car consumes about 500 GJ of gasoline during a decade of its service, five times its embodied energy cost. A smartphone consumes annually just 4 kilowatt-hours of electricity, less than 30 megajoules during its two years of service, or just 3 percent of its embodied energy cost if the electricity comes from a wind turbine or from a photovoltaic cell. That fraction rises to about 8 percent if the energy comes from burning coal, a less efficient process.

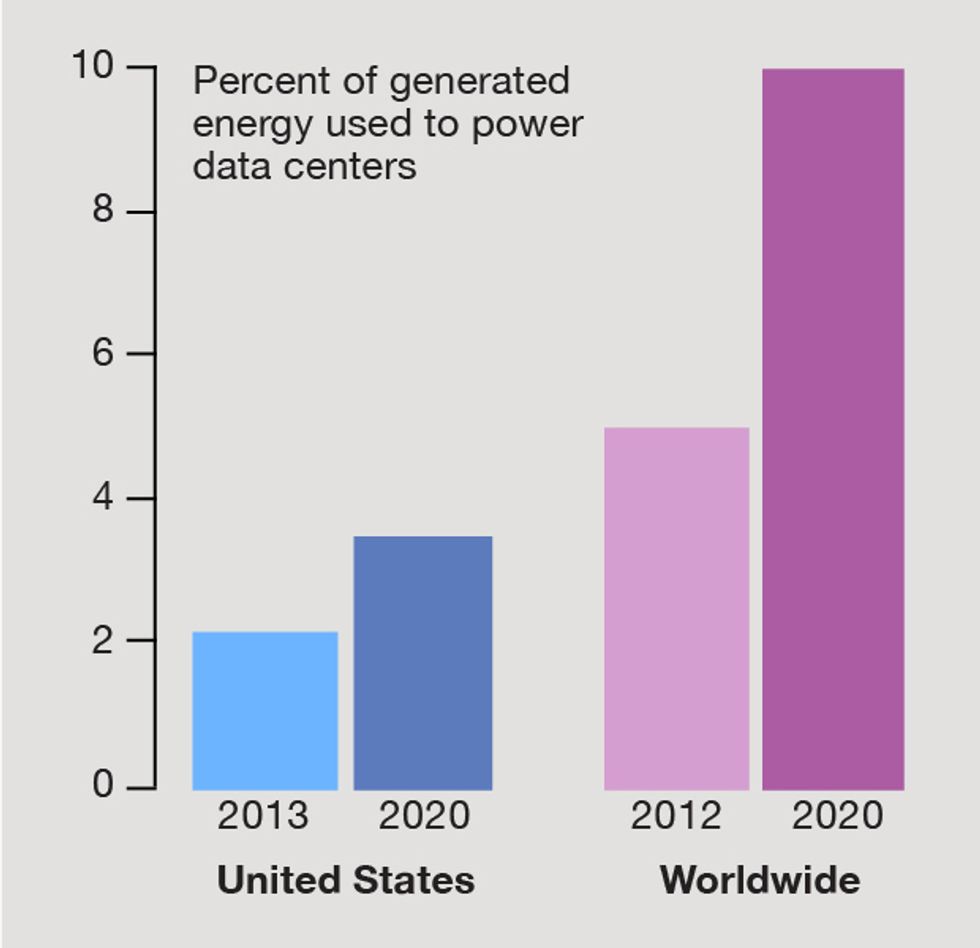

But a smartphone is nothing without a network, and the cost of electrifying the net is high and rising. In 2013, U.S. data centers consumed about 91 terawatt-hours of electricity (2.2 percent of all generation) and are projected to use about 3.5 percent by 2020. Around the world, overall demand of information and communications networks claimed nearly 5 percent of electricity generation in 2012, and it will approach 10 percent by 2020. In aggregate, those tiny phones leave quite a footprint in the energy budget—and the environment.

This article appears in the May 2016 print issue as “Embodied Energy: Mobile Devices and Cars.”