Editor's note: In this guest post, Japanese roboticist Masaaki Kumagai, an IEEE member, describes the moment when the 9.0 magnitude earthquake hit Japan on March 11 and the two weeks that followed. Dr. Kumagai is an associate professor at Tohoku Gakuin University, in Sendai, a city of 1 million on Japan's northeast coast and one of the most affected by the quake and ensuing tsunami. This is part of IEEE Spectrum's ongoing coverage of Japan's earthquake and nuclear emergency.

March 11, Friday — Day 0

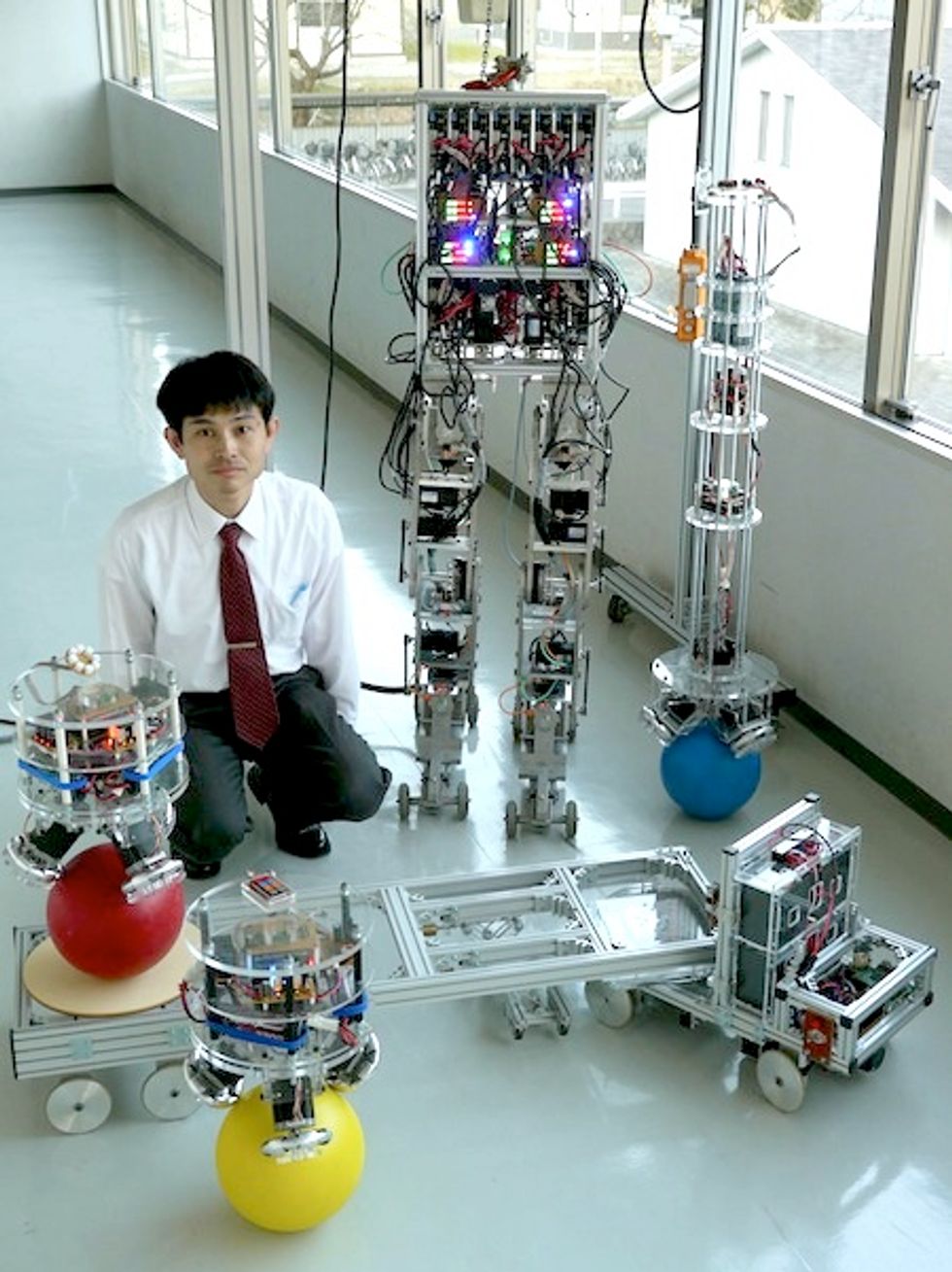

It was a cold morning, sometime before noon, and I was preparing our robots for a demonstration scheduled for Sunday at the Sendai Literature Museum. They were having a science fiction exhibit and had asked me to bring some robots for visitors to see. My plan was to take two BallIP robots—machines that self-balance on balls—and a truck-like wheeled robot. I charged their batteries and began to carry the equipment to my car, which I had parked near my laboratory on Tohoku Gakuin University's Tagajo Campus. At around 2:45 p.m. I had nearly finished loading the car and was walking back to the lab to grab a few more things.

Suddenly I heard a roar from the ground. An instant later everything started shaking. I looked at the building where I have my lab and the windows were vibrating so violently you'd think they were going to explode, though only a few actually did. The shaking continued for what it felt like a long time. Its intensity increased, decreased, and then increased again, and that cycle repeated itself a few times. During the tremor, I was able to stand without losing my balance. My father would later tell me that the shaking was much more violent at other parts of the city and people had to hold on to walls and furniture to avoid falling.

When the shaking finally stopped, people came out of the building. My students seemed to be okay. They told me that there was no severe damage inside, except for books, papers, and other objects that had fallen from shelves.

I thought of my wife, Keiko. She was home, and I believed she was safe. I wanted to talk to her. Unfortunately, I didn't have my cellphone with me. I had left it inside my bag in my office. People who had cellphones were having trouble using them: It appeared that service was down or overwhelmed. Fixed lines were having the same problem. I needed to go home.

Then another problem. The Japan Meteorological Agency sent out an “alarm of large tsunami." Until today, that alarm, with this severity level, had been used only twice in Japan in the past two decades. University personnel began guiding people to a higher-level area of the campus. The warning said that there would be 10 meter-high tsunami waves hitting the Sendai shores.

Some students became agitated. They were watching TV on their cellphones (many cellphones in Japan have digital television receivers). The news reports showed tsunami waves already flooding Sendai Airport, which is about 1 kilometer from the coast. Even watching the videos, I could not—or did not want to—comprehend what was happening.

My students and I discussed what to do next. Of course, they wanted to go home. Public transportation was crippled, though; rail service had completely stopped. Two of them decided to go home by themselves; two others preferred to wait on campus for their parents to pick them up later. I decided to take three other students in my car to a central area of Sendai, where they'd probably have better luck with transportation.

To make room for the students in my car, I removed the robots and other gear. Well, not everything. Just in case the museum event happened as planed (at that point I had no idea how severe this disaster was), I kept a minimum set of equipment, including a BallIP robot, in the trunk.

Someone told me that water had covered a large area south of our campus. We had to avoid those streets. As we drove, we hit a heavy traffic jam. Almost all traffic lights weren't working due to a wide power outage, and no police officers were on the streets, even at major intersections.

Along the way, we saw cracks and bumps on the road, damaged walls, parts of traditional ceramic Kawara roof tiles broken, and overhead wire poles for the Shinkansen rail service tumbled on the tracks. But we didn't see collapsed houses, buildings, or bridges, which was a great relief.

On our way to central Sendai, I made a quick stop to see my grandmother at her house. Though she lives alone, that was the day when my mother and my aunt visit her. I was very happy to see all of them there. They did not know about the tsunami, because the power was out and they couldn't use the radio or TV. My mother said she would stay through the night with my grandmother. And she told me that my father had called and he, too, was safe.

I departed with the students and we hit another traffic jam. At that point the students decided to walk. I worried about them and hoped I would hear from them soon. Next, I made another quick stop at the main campus of our university, where I found some 100 people sheltered in a cold and dark gym. I talked to some administrators and left.

It usually takes me less than an hour to drive from the Tagajo Campus to my house in Yagiyama, a residential area in Sendai. On this day, my commute home was an excruciatingly long journey that lasted nearly 6 hours. On a normal day, I could drive to Tokyo, some 350 kilometers away, in less time.

When I finally got home, I opened the door and ran inside, where I found Keiko. She was okay.

At that time, we still had running water, so we poured as much as we could into bottles and pans. I knew that without electricity, the water would stop soon because our residential area is on a hill and it depends on pumps.

We ate rice cakes and fell asleep. It was the end of a very hard day.

March 12, Saturday — Day 1

We got up late that morning. Electricity and Internet service were still down, and the water had stopped. It was confirmation that it wasn't all a bad dream—this was real.

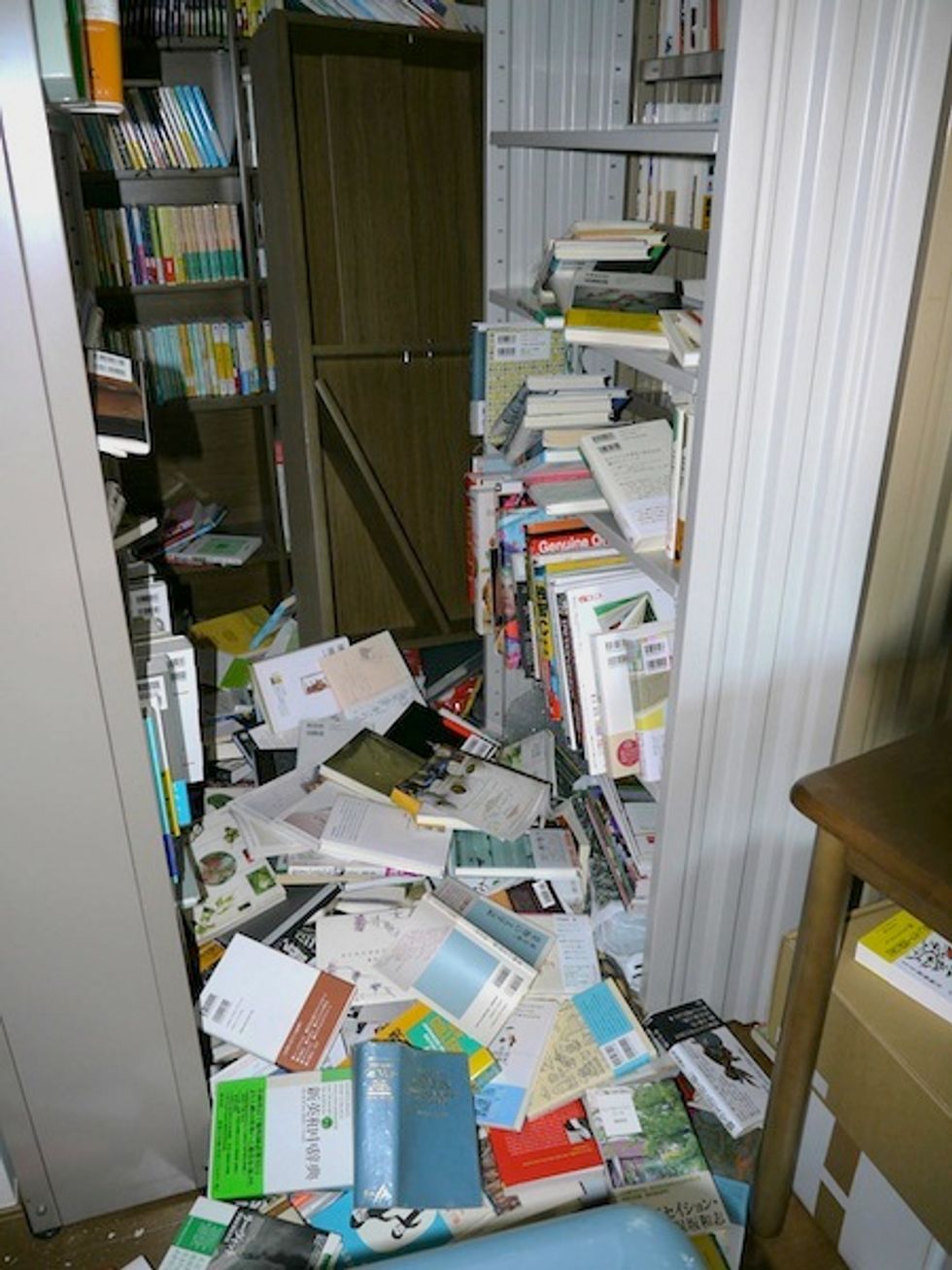

I walked around the house. The biggest damage were two bookshelves that turned over [photo below]. The bigger one came crashing down on my Linux server and network-attached storage box. I set up the server for monitoring my house and my parent's house using Net-enabled cameras. (Later, after electricity returned, I watched the footage recorded right before the earthquake cut off power.)

Without Internet, television, or cellphones, all the information we received was from an old transistor radio powered by dry batteries. It was enough for us to know how terrible this disaster was. From our balcony, we gazed at the city stretching towards the Pacific Ocean. We could see several dark areas: places near the shore flooded by the tsunami.

We ate rice cakes, crackers, and cookies. The sun set. We went to bed.

March 13, Sunday — Day 2

I drove to my grandmother's house with my mother to bring her a microwave oven. Hers had fallen off a table and broken during the earthquake. On the way, we saw several buildings damaged in the central area of Sendai. No building had completely collapsed or tumbled, but parts of their walls had fallen off. There were also huge cracks on streets and sidewalks [photo below]. Many areas had been barricaded to keep pedestrians safe.

When we arrived at my grandmother's place, we found that the electricity had returned. The phone line was also working, and so was water service. It was nice to know that my grandmother could live a bit more comfortably. My uncle and aunt stayed with her.

March 14, Monday — Day 3

Electricity returned!

Cellphone service (PHS system) was partially working, and e-mail service became available. I started to contact people to find out whether they were safe, and to let them know that I was okay. I sent an e-mail to a popular robotics researcher and blogger, Dr. Fumi Seto, asking her to repost my message on Twitter, which was a good way to reach many colleagues and friends. Using e-mail, I confirmed that most of my students were safe.

With electricity back, we could use the microwave oven and heaters, which changed our life drastically. We could warm our house easily and could have hot meals. Most of the food in the refrigerator was still good. That was very good news.

I figured that even in moments of adversity it's important to keep your mind busy. So I thought I'd do an experiment. I took a BallIP robot—the one I had kept on the trunk of my car—and loaded it with a fresh pack of batteries. BallIP is a robot that balances on a ball. For a long time, even before the earthquake, I had pondered this question: Can BallIP keep its balance during a tremor? In the days after the quake, there were many aftershocks with seismic intensity of up to 4. (Japan Meteorological Agency's rates the intensity of tremors at different locations using a seismic intensity scale, which varies from 0 to 7.) Of course I did not wish more tremors to happen, but this was a chance to do some science, so I kept the BallIP running in my living room [photo below].

March 15, Tuesday — Day 4

It was 4:30 in the morning when I got out of bed and realized that the phone line and optical fiber network service had returned. (About 35 percent of residences in Japan have optical network service.) I immediately booted up my PC and stayed on Twitter for several hours. I reported that we were safe and responded to questions.

One person asked me if I had access to power, water, Internet, and food normally. I responded that although I had electricity, phone, and Net, I didn't have water, gas, gasoline, oil, or food supplies. Nothing is normal, I said, explaining that I was surviving with what I had stocked in my house.

I read that many schools on the eastern part of Japan were closed: March is graduation and April is the start of the school year, but ceremonies were cancelled or postponed.

I received confirmation that more of my students were safe. However, two students had not responded yet.

At the end of the day, after sitting in front of the TV and the computer, trying to absorb everything that was happening, my head started to spin. I felt anxious and couldn't think clearly. I went to bed.

March 16, Wednesday— Day 5

One of the two students I was still trying to contact replied to my e-mail and confirmed that he was in his hometown and safe. I began to search the name of the last student on the Net using Google's Person Finder and lists of people in shelters.

My wife walked around the neighborhood and found canned coffee on a vending machine. Canned water, tea, and coke were sold out, but coffee looked in poor demand for some reason.

My university department, which had recovered Web service two days ago, announced that faculty, staff, and students could not enter rooms and laboratories until a safety inspection was completed.

I found out that I had lost 2 kilograms.

March 17, Thursday — Day 6

The City of Sendai announced that water service, which had returned in several areas, would not return in our neighborhood until the end of March. For now we had to rely on bottled water to drink. And we had about 1000 liters of rain stored in a water tank, a storage system designed and built by my father [photo below].

I moved my main PC from my study to the living room, so we could live only in one room, which could reduce fuel and electricity consumption.

I thought about going to campus, but then my department reiterated its previous announcement: No one could enter the building.

In the evening, BallIP was running in the living room when there was an aftershock. It reportedly had a seismic intensity of 3 in our area. The robot didn't lose its balance. I suspect that the inverted pendulum control approach might be able to adapt to earthquakes. I have no idea if this could have any practical applications. But someday I hope to confirm this hypothesis by testing BallIP using Gurara, an earthquake simulator that the city built so residents can experience earth tremors.

March 18, Friday — Day 7

A colleague checked an online directory and found out that the last student we were looking for was safe.

An editor of a technical journal asked me to review two papers. I guess she assumed I could not go to the university and therefore had some free time. She was right. I accepted to do the reviews.

I walked around the neighborhood. A supermarket opened, and about 30 people waited in line, which was shorter than I imagined.

I tried the robot software platform OpenHRI, which I found very interesting. I experimented with its voice synthesis and voice recognition features for a few hours.

The first week passed very quickly.

March 19, Saturday — Day 8

I went to a drugstore with Keiko and bought medicine for pollen allergies.

When I booted my PC, its bios detects a RAID error on one of two hard drives. Very scary. Fortunately I used my laptop PC to do a search and found a fix. Phew.

I shaved for the first time since Day 0. I should have taken a photo of my unshaven face, for posterity.

March 20, Sunday — Day 9

My parents, my wife, and I went to my grandmother's house to fill bottles with water. We filled 18 2-liter bottles, which might last for three or four days. (It is said that a person requires 3 liters of water a day.)

In the house, there was a washbowl with electric-heated water, and I washed my hair. Subsequently, my father tried to wash his hair but complained that the bowl was too small. I found out that my father's head is larger than mine.

On our way home, we picked up a package from relatives who live in Hiroshima. Door-to-door delivery service (like UPS or FedEx) was not operating, so we picked up the parcel at an office of the carrier. The contents: dried foods easy to prepare, dry shampoo that doesn't require water to wash hair and body, and cleaning products.

I had been worrying about a former high school teacher who lives in Kesennuma, one of the areas most affected by the tsunami. I searched for his name on Google's Person Finder and found that he and his family were all safe.

TV programming began to return to normal. A yearlong historical drama on NHK has resumed. Of course, NHK and other channels continue to broadcast news and documentaries on the earthquake, the tsunami, and the Fukushima nuclear plant crisis during most of a day.

March 21, Monday — Day 10

I received a message from the last student I was trying to reach. It was the best news of the day.

A note came from the Sendai Science Museum that it suffered lots of damages and would remain closed until the summer. Every year, a group of colleagues and I organize a robotics competition called Intelligent Robot Contest at the museum. I suggested to the other organizers that we cancel this year's contest.

March 22, Tuesday — Day 11

I finished reviewing the two papers and sent my comments to the editor.

March 23, Wednesday — Day 12

My father had some errands to do in Sendai and took me with him as a “car sitter" because we didn't know if parking was available in the city. Many parts of town had severely damaged streets. Before we went home, we stopped at an electronics shop where we usually buy many electronic parts. It looked like it had been closed since the earthquake, but it opened just as we arrived there. They said that many cabinets had turned over, spilling all the parts on the floor, and it took days to recover. But they wanted to get back in business soon because they thought many engineers would start looking for parts.

I downloaded OpenHRP3, a platform for robot simulations and software development. I had never used dynamic simulator for my projects (because I'm not good at equations!), but this tool looked useful for testing a large robot design I had in mind for a future project.

The journal editor asked me if I could review a third paper. She really knew I had some free time in my hands.

March 24, Thursday — Day 13

The latest issue of the Journal of the Robotics Society of Japan arrives—with a delay of only five days. It was the first large envelope we received in days (the mail service was only delivering postcards and regular-size mail previously). It was a special issue about publicizing robotics research to a general audience and it included an article I wrote about a BallIP video posted on IEEE Spectrum's YouTube channel that received hundreds of thousands of views.

A worker for the gas service company came to close the main gas line in our house (I had already closed it after the earthquake, and he checked and sealed it). This was good news because closing all lines at people's homes was essential so the company could check for leaks on pipes under streets and repair any damages.

Keiko dragged me to the supermarket. There were many more products on the shelves than I had imagined (TV news reports were always saying there was a lack of products). However, it was a strange sight. Some products had large amounts in stock; others had nothing. For instance, there are usually a hundred brands of instant noodles, each with 10 to 30 cups on the shelves, but today there were only two brands with over 200 cups each!

I received an e-mail from my department saying that the first faculty meeting would take place on April 7. It would be an official restart of our school work.

The university announced that we could enter the building because the safety inspection was finished.

I wanted to go to the campus, but I needed gasoline for the car, which was still hard to find. In fact, lack of fuel was one of the most serious problems in our area and elsewhere. It limited transportation, logistics, and recovery work. I decided to stay home for a few more days.

March 25, Friday — Day 14

I finished reviewing the third paper—much faster than usual.

Water service recovered! I realized, more than ever, how important water is.

Gas service still interrupted. We used an oil heater to warm the bath water.

March 26, Saturday — Day 15

I used OpenHRP3 to build a dynamic model of a ball-balancing robot. It was my first time using this dynamic simulator, and it was both hard and interesting. I could even test it with the real robot, by connecting it to an external controller with RT-Middleware.

A parcel from Akizuki, an electronic parts shop popular among Japanese engineers and hobbyists, arrived by home-delivery service. It contained 15 hand-powered flashlights, which don't need batteries and are so useful during power outages. I decided to give one to each of my students.

Postscript

On March 27, Day 16 after the earthquake, I started to write down what I have experienced since Day 0. I thought it would be important information for myself, my family, and maybe others in the future, when the next earthquake hits. I usually have poor memory, but I remember vividly so many things that happened on the day of the quake and the days that followed. I wrote this document in Japanese; what you read here is a version—translated into English and edited—of the first 15 days. I continue to write my diary.

On March 30 (Day 19), I finally returned to the Tagajo campus. While driving through Tagajo City I saw many destroyed vehicles. Some had lost the shape of a car completely. There were even trucks turned over. I had seen these scenes on TV but it was quite different to see the destruction with my own eyes. It was so scary.

As of mid April, gas service finally returned at my house. Cooking is much easier now.

I have now met all the students who were at the lab when the quake happened. They look fine, and were preparing to recruit new members to their robotics club.

In late April our university started orientation for the new students. I need to explain to them how to choose courses—and everything else they have to do to graduate. Classes are scheduled to start this month.

Though the situation is still challenging, it is getting better day by day. I thank all the people supporting our recovery.

Masaaki Kumagai, an IEEE member, is the director of the Robot Development Engineering Laboratory at Tohoku Gakuin University. He's a faculty member in the university's department of mechanical engineering and intelligent systems. Dr. Kumagai, born in Sendai, has a PhD in engineering from Tohoku University. From September 2009 to August 2010, he was a visiting professor at Carnegie Mellon University's Robotics Institute. Follow him on Twitter at @kumarobo.