Transportation produces about one-fourth of global anthropogenic carbon emissions. Of this, maritime shipping accounts for 3 percent, and this figure is expected to increase for the next three decades even though the shipping industry is actively seeking greener alternatives, and developing near-zero-emission vessels.

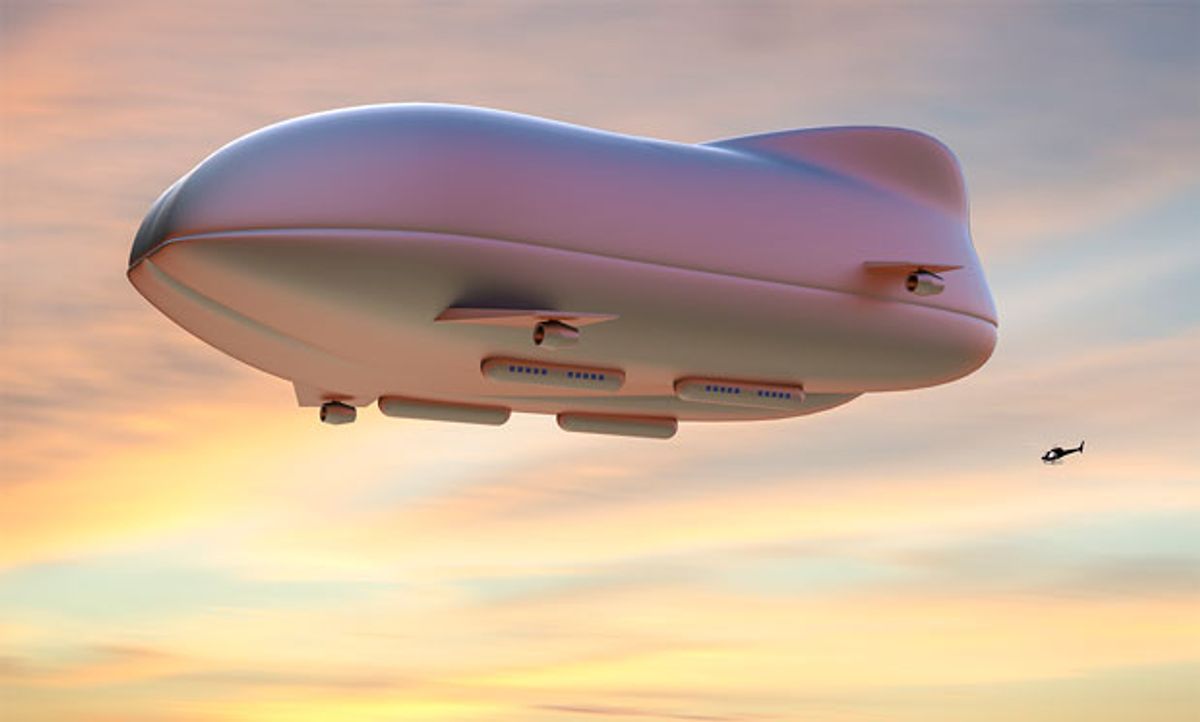

Researchers with the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis (IIASA), in Austria, recently explored another potential solution: the return of airships to the skies. Airships rely on jet stream winds to propel them forward to their destinations. They offer clear advantages over cargo ships in terms of both efficiency and avoided emissions. Returning to airships, says Julian Hunt, a researcher at the IIASA and lead author of the new study, could “ultimately [increase] the feasibility of a 100 percent renewable world.”

Today, world leaders are meeting in New York for the U.N. Climate Action Summit to present plans to address climate change. Already, average land and sea surface temperatures have risen to approximately 1 degree Celsius above pre-industrial levels. If the current rate of emissions remains unchecked, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change estimates that by 2052, temperatures could rise by up to 2 degrees C. At that point, as much as 30 percent of Earth’s flora and fauna could disappear, wheat production could fall by 16 percent, and water would become more scarce.

According to Hunt and his collaborators, airships could play a role in cutting future anthropogenic emissions from the shipping sector. Jet streams flow in a westerly direction with an average wind speed of 165 kilometers per hour. On these winds, a lighter-than-air vessel could travel around the world in about two weeks (while a ship would take 60 days) and require just 4 percent of the fuel consumed by the ship, Hunt says.

The IIASA-led study, conducted by a team from Austria, Brazil, Germany, and Malaysia, also proposes combining the transport of hydrogen along with cargo on airships that use hydrogen as the lifting gas. “An aspect that will considerably increase the viability of airships and balloons is the development of a hydrogen economy,” Hunt says. Given that airships are already a clean technology (the only by-product of hydrogen-based fuels is water), using them to also transport hydrogen could offer an additional advantage of this transportation mode.

However, many people still associate airships with the tragic Hindenburg disaster in 1937, when a hydrogen explosion resulted in 36 deaths and earned airships a reputation as unsafe. The hydrogen-filled airships mentioned in the IIASA study do have a potential risk of explosion, and are not suitable for passenger travel.

But Hunt says that with new materials such as graphene that are lighter, more durable, and more flame resistant, the risks are considerably lower. He also suggests taking additional safety measures, including flying routes that avoid densely populated areas. And, says Hunt, if problems do occur while an airship is operating, “the airship should be evacuated and blown up in the stratosphere” and also come equipped with a mechanism to safely unload any other cargo (with parachutes, for instance).

Most modern airships, though, use helium instead of hydrogen as the lifting gas, including those developed by the company Flying Whales, which aims to begin delivering cargo to remote areas in 2023, and the hybrid airships built by Lockheed Martin for Straightline Aviation.

“Helium is an inert gas,” says Mike Kendrick, CEO of Straightline Aviation, which is expecting its helium-based hybrid cargo airships to lift off in early 2021. “[It’s] not quite as efficient as hydrogen [and more expensive] but much safer.” (The hybrid vessels made by Lockheed Martin, unlike conventional airships, are heavier than air.)

The most energy-intensive part of airship operations comes when its lifting gas has to be pressurized to allow for descent. If the energy released during depressurization (during lift) can be stored and reused during descent, every trip could theoretically have a net zero energy use. And any hydrogen fuel onboard could be supplemented by solar power arrays on the airship’s surface, says Hunt.

“If you try to estimate the cost [of using airships for cargo] now, it would be 10 to 50 times more expensive than ships, [which] are a mature technology that has been developing for hundreds of years,” Hunt says. For airships to be competitive with conventional shipping, he adds, the cargo industry would have to invest at least US $50 to $100 billion over the next decade or two in developing the technologies required to make it a safe and efficient means of transportation.

Editor’s note: This story is published in cooperation with more than 250 media organizations and independent journalists that have focused their coverage on climate change ahead of the U.N. Climate Action Summit. IEEE Spectrum’s participation in the Covering Climate Now partnership builds on our past reporting about this global issue.

Payal Dhar (she/they) is a freelance journalist on science, technology, and society. They write about AI, cybersecurity, surveillance, space, online communities, games, and any shiny new technology that catches their eye. You can find and DM Payal on Twitter (@payaldhar).