Facebook vs. Google: Game On

FarmVille has led a social-game ascendance that will sway the Facebook-Google struggle and threaten the digital gaming industry

This is part of IEEE Spectrum’s special report on the battle for the future of the social Web.

The hottest trend in gaming isn't aliens or wizards. It's something more down to earth. The grass is green. Guitar chords drift lazily from a front porch. And the crops are ready for harvest.

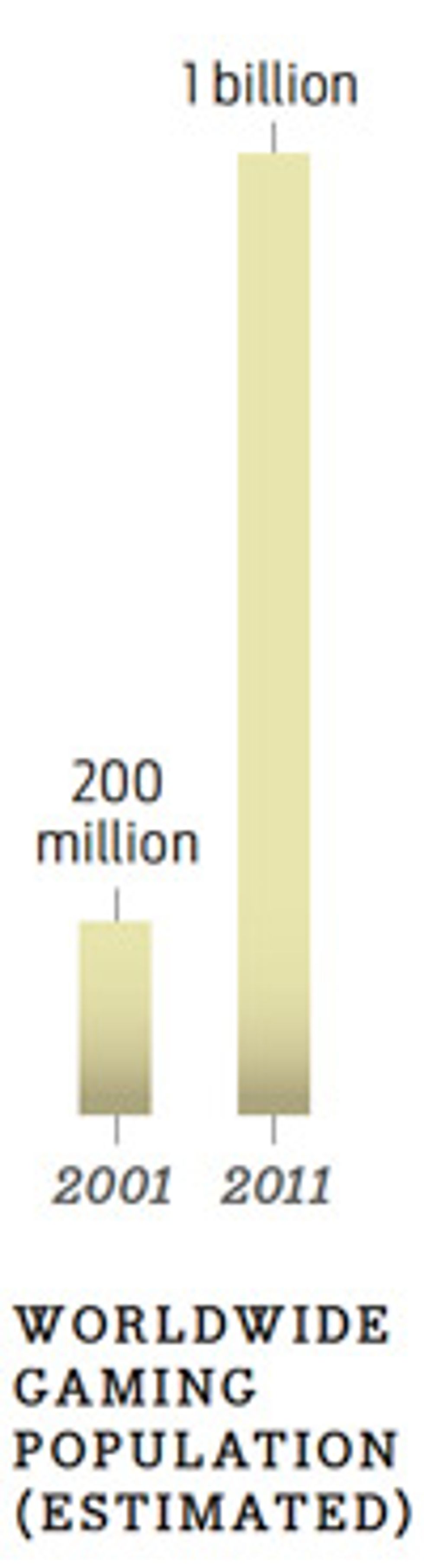

Such are the bucolic pleasures of FarmVille, the Facebook game that led the way in a games revolution that transformed how hundreds of millions of people are entertained online. In the process, a new generation of players has pushed aside the stereotype of the lonely teen in the basement. Instead, she's the middle-aged mom harvesting virtual corn in FarmVille. He's the commuting executive with his iPad, slingshotting evil green pigs in Angry Birds. They're the retirees on their iPhones playing Words With Friends.

Video games are in a renaissance. Even as game developers continue to churn out big-budget shooters and sports games for the trinity of home consoles—Microsoft's Xbox 360, Sony's PlayStation 3, and Nintendo's Wii—the real action is migrating to a decidedly less hard-core arena: social networks and mobile applications.

According to the Nielsen Co., the top two activities for Americans online are social networks and games—together accounting for about a third of our time on the Net (one casualty: time spent on e-mail, which dropped nearly 30 percent in the past year). Those two trends converge in games like FarmVille. It boasts more than 50 million monthly players, and its sequel, CityVille, is fast on its way to surpassing 100 million a month, according to the website Inside Social Games. The explosion of such "social games"—games played on social networks—has been aided by a perfect storm of broadband penetration, wireless connectivity, and mobile platforms. And it's made Zynga Game Network, creator of the "Ville" series (which includes FrontierVille, FishVille, PetVille, and YoVille), the second biggest publisher in the game business, worth as much as US $9 billion, according to The Wall Street Journal. Zynga, based in San Francisco, is now bigger than Electronic Arts, the industry mainstay famous for the chart-topping Madden football and Sim City franchises. The communal aspect is central to Zynga's strategy. As Dorion Carroll, chief of technology of the shared technology group for Zynga, says, "We're not a gaming company. We're a social gaming company."

Games are profoundly shaping the future of the Web and, as a result, the strategies of the two biggest players online: Facebook and Google. The annual Game Developers Conference is the usual place where people take the pulse of the industry. And at this year's conference, the two companies loomed large. The panels on Facebook games and Google's two-day-long developer summit were both jammed.

The companies' interest in games reflects their differing visions: the openness and decentralization of Google versus the walled-but-thriving community of Facebook. "Games for Facebook are a mechanism to drive you to the page and keep you there," says Michael Pachter, an analyst with Wedbush, a Los Angeles–based financial services firm. "Games for Google are to drive you to their [Android operating system] and keep you there. It's different strategies and outcomes."

Social games aren't new. Before computers, games were inherently social, because essentially all of them were meant to be played by two or more people. The new social games, however, have a fundamentally different purpose. Socialization isn't meant to enhance the games; the games are meant to enhance socialization. They've been designed to do that for a very specific and simple reason: The more people who hang out online, the more Facebook and Google can cash in.

By attracting specific demographics of players and uncovering information about their habits, preferences, and acquaintances, social games are tailor-made for supporting targeted advertising. Moreover, players can enhance their experience by purchasing digital items with credits, for which they pay real cash in the real world. If you think no one but a misfit would spend hard-earned money on a virtual crop duster, you're wrong: Zynga alone is pulling in $1 billion that way, according to estimates by Wedbush. And by taking a 30 percent cut of all credit purchases made through all its games, Facebook earns roughly $500 million a year.

To reach a wide market, the more accessible such games are, the better. FarmVille isn't Grand Theft Auto or Halo or some other blockbuster that demands dozens of hours of play and thumbs that dance like Lady Gaga to achieve competence. The object of FarmVille couldn't be more straightforward: You run a farm with the help of your online friends. It's a light diversion, something you enjoy in installments. The simplicity lends itself well to smartphones, allowing games to fill tiny gaps of downtime throughout the day.

Zynga alone is pulling in $1 billion that way”

As Facebook's membership exploded in 2008 and 2009, so did its games. Led by FarmVille, Zynga grew from 16.9 million monthly active users in September 2008 to 200 million in November 2009, according to Inside Social Games. And the surge isn't limited to Zynga. In April 2010, PopCap Games, the Seattle-based creators of the hit puzzler Bejeweled, launched a Facebook version called Bejeweled Blitz that quickly racked up 3.8 million daily players. PopCap attributes the success, in part, to Facebook's use of real identities for members; that appeals to casual gamers and sets Facebook apart from the faceless free-for-all of other online games. "People are far more comfortable playing with people they really know," says Jon David, vice president of social games for PopCap.

With games now attracting so many eyeballs and dollars, Facebook is ramping up its strategy in the market. Last November, the company hired a dedicated director of engineering for game platforms: Cory Ondrejka. The cocreator of Linden Labs' pioneering virtual world Second Life and Linden's former chief technology officer, Ondrejka says games are central to the mission of the site. "Games on Facebook are inherently social," he notes. "The whole point of putting a game on Facebook is that you can play with friends."

Engineering a Facebook game has its appeal: It can cost as little as $100 000 to develop, which is peanuts compared to the tens or even hundreds of millions that go into a sophisticated console game. But so many game developers rose early to the challenge that Facebook users were quickly overwhelmed, as developers essentially spammed users through news feeds and wall posts. In March 2010, Facebook finally put restrictions on such viral promotions. Users welcomed that reform, but for developers, it made publicizing their new games harder.

For those lucky developers who do manage to get the word out, Facebook success can pose its own headaches. With FarmVille, Zynga had to quickly scale up a game from zero users to more than a million in just days, while simultaneously readying the game to add still more millions as word spread. Prior to FarmVille, the company ran its games on racks of computer servers in designated data centers. As the game exploded in popularity, however, Zynga engineers had to change their approach.

"We simply could not have acquired and configured hardware fast enough to meet the user demand," Carroll says. Instead, the company switched to Amazon Web Services, a cloud computing solution, which allowed it to take advantage of Amazon's elastic supply of processing power but "also meant that we needed to learn a lot of things all over again," he adds.

The challenge for Facebook now is how to expand its portfolio of games. Ondrejka is betting on new tools that will enhance and vary the kind of game experiences players can have on the site. "It's on us to push technology forward wherever we can," he says, whether that means calling for faster CPUs and browsers or greater availability of wireless spectrum. "Right now there's an intense arms race to make browsers better," he says. "How do we make sure those better browsers enable developers to make better games and reach more users?"

In particular, Facebook is exploring the potential of Hypertext Markup Language 5, or HTML5, the latest version of the standard Web programming language. Ondrejka calls it "a potent platform for game development," citing HTML5's robust handling of video and audio. According to Facebook, more than 125 million people are already using HTML5-equipped browsers on their mobile phones.

But the company still has concerns over the language's low performance and frame rate. One complication, Ondrejka explains, is that HTML5 offers "myriad different approaches" to drawing the images that appear on-screen, but it isn't always obvious which technique will work best in the context of a specific game. Consequently, Facebook devoted one of its all-night "hackathon" research-and-development events to creating the JSGameBench software, to test the limits of HTML5 for game performance. Developers are now using the code to see how many two-dimensional objects—known as sprites—HTML5 can generate at a time.

But for all the open-source innovation, how open will Facebook's gaming future really be? Some game developers have criticized Facebook for what they see as excessively harsh and autocratic behavior. For two days this past October, for instance, Facebook banned all games by the company LOLapps for violating Facebook's privacy policy. The fact that LOLapps games were being played by 150 million Facebook members at the time, according to The Wall Street Journal, sent a chill through other developers. "Facebook has the power to shut down an entire company," warned Daniel Cook, chief creative officer of the social game developer Spry Fox. Cook made his comment during a panel at the Game Developers Conference entitled "How to Survive the Inevitable Enslavement of Developers by Facebook."

Ultimately, episodes like this lead Facebook's critics to the same conclusion: that Facebook is a walled garden that fails to honor the spirit of openness on which the Internet was founded. They have a point: Facebook, and only Facebook, gets to decide who can come inside and play. Ondrejka, however, bristles at the suggestion that Facebook is cloistered. "Looking at it as a walled garden is probably the wrong way to look at it," he says. "It's important that we continue to make it as open as we can."

Game designer Graeme Devine agrees. "Users don't see Facebook as a walled garden," he says, "so developers shouldn't see it that way."

But many developers do see it that way—particularly ones that aren't earning a billion dollars a year from Facebook. Google, too, has adopted a very different strategy for games and is quite happy to talk about it. "Strategically as a company, it's just our personality. We stay away from walled gardens," says Ian Ni-Lewis, the senior developer advocate on Google's gaming relations team. "The advantage to getting out of a walled garden is that everybody is on a level playing field. Consumers have more choice."

Google's interest in gaming has soared in the past year. According to Ni-Lewis, on phones running Google's Android open-source operating system, over 60 percent of the paid apps are now games. Game-related videos are the second most popular type of video on YouTube, which Google owns. And as Google pushes HTML5 programming as part of its Chrome Web browser, there's no doubt where demand will come from. "The only things people get excited about with HTML5 are games," says Ni-Lewis. "They drive our technology and drive our platform."

Google's gaming plan is twofold: to encourage developers to use Chrome and Android phones as distribution platforms and to employ Google tool sets for game creation. Ultimately, anything good for the Web is good for Google, and the more that Google can nurture online games, the more it stands to gain from ad sales and other revenues.

Developers are already employing Google tools such as App Engine (a cloud computing service), SketchUp (a 3-D graphic design tool), and software development kits for Android handsets. One of the most compelling new tools that Google is pushing is WebGL. This 3-D Web-based graphics library promises to bring to compatible browsers such as Chrome the kind of immersive graphics seen in first-person-shooter and adventure games on consoles.

Unlike Facebook or Apple's App Store, the Chrome Web Store offers developers a means to distribute their games online without interference or the 30 percent fee on every transaction that Facebook and Apple claim; Google's cut is reportedly only 10 percent. Also, following the lead of Zynga's FarmVille, Google recently introduced microtransactions for online purchases of, among other things, virtual game items—a development seen as central to growing Chrome and Android as robust platforms.

The model for Google here is Apple. Apple's app-store data show that 7 of the top 10 paid apps on Apple iPhones and iPads are games. The games support the hardware's popularity, and vice versa. "Given the success Apple had with smartphones and iPads, Google looks at that and says, 'Obviously we need to be there,' " remarks Colin Sebastian, a director and senior analyst with Lazard Capital Markets in New York City.

"Google is thinking about global domination," adds Wedbush's Pachter. "Google is looking at games as apps that will sell its OS and make Google more essential as an operating system," thereby replicating the success of games on Apple's mobile operating system, iOS. He thinks Google "will very likely succeed."

Yet for developers, migrating to Google offers mixed prospects. On the one hand, the company's tool sets are empowering. "Google understands that a platform that is implicitly and totally trusted by developers and consumers will become unimaginably valuable over time, by eventually identifying a friendly, 'nonevil' method of generating profit," says Spry Fox's Cook.

But coding a game for Android requires testing it on a variety of handsets, because each manufacturer tweaks the operating system to meet its needs. That testing process takes additional time and labor. Moreover, releasing a game outside of Facebook means missing out on the hive of dedicated gamers built into its audience. As a result, developers are more inclined to design a product with the social network in mind. "Initially targeting Facebook isn't a bad strategy," says Colin Macdonald, vice president of business development for eeGeo, a social game developer based in Dundee, Scotland.

Whether or not developers adopt Google's tools also depends in part on the adoption of Chrome. "If WebGL and Chrome are advancing and enough people are using the technology, then we want to [work with] that," Zynga's Carroll says. But "we have to wait until [the] audience adopts that." David of PopCap describes these early days of HTML5 as a "wait and see" phase, which developers will adopt if and when the language proves robust.

The competition over games is part of the larger conflict between Facebook and Google over whether (and how much of) the Web will be open or closed. Yet it's not necessarily a winner-take-all battle. The companies are also allies in a sense, because they both hope to pry eyeballs away from the video-game consoles and dedicated handhelds and onto cellphones, tablets, and PCs. And so the success of one may help the other.

"In a lot of ways it's just collaboration," says Ni-Lewis. "The idea is that we want to advance these open standards." Facebook's Ondrejka agrees, calling Google's work on Chrome "extraordinary" and the innovations for Android and HTML5 just as encouraging. "They're making increasingly broad platforms better," Ondrejka says. And that bodes well for both companies, no matter what games people are playing.

Nevertheless, the success of Facebook and Google in gaming poses a twofold threat to console game developers. Many social games are either free or cost less than a dollar. So some companies producing $60 console games worry that the market for their kind of highly advanced games is going to wither.

In addition, there's concern that the flood of inexpensive, lower-quality titles could sour the public's appetite for games. (Something like this happened before: The first golden age of video games ended with the release of a lackluster E.T. movie tie-in game.) During a standing-room-only keynote speech at the 2011 Game Developers Conference, Nintendo president Satoru Iwata shocked the crowd by noting that the thousands of console games on the market paled beside the tens of thousands of games online. "Game development is drowning," he said.

Despite such concerns, these are still very good times for the industry. As an entertainment form, games are as popular as they've ever been. There's even a new buzzword—"gamification"—which describes the infiltration of gamelike experiences into everyday life. Global game sales now top $60 billion and are expected to top $70 billion by 2015, according to DFC Intelligence, a technology research firm based in San Diego.

There's nothing like a good round of Madden NFL on a PlayStation 3 and a 56-inch screen. Facebook and Google probably won't ever be able to replicate that. What they've done is expand the market by bringing games to people who probably would have never become gamers otherwise, just as in the 1950s and 1960s TV expanded the distribution of entertainment beyond movie theaters. The wizards and space marines aren't dying. They just have some new friends down on the farm.

This is part of IEEE Spectrum’s special report on the battle for the future of the social Web.

This article originally appeared in print as "Betting the Farm on Games."

About the Author

Contributing Editor David Kushner is the author of Masters of Doom (2003), Jonny Magic & the Card Shark Kids (2005), and Levittown: Two Families, One Tycoon, and the Fight for Civil Rights in America’s Legendary Suburb (2009). He recently wrote about the reinvention of music games in “Music Gaming Won't Die.”