Surf Africa

Africa lit a shiny new fiber-optic undersea cable almost two years ago—so why are so few Africans using it?

Johnson I. Ejimanya is a one-man pony express. Walking the exhaust-fogged streets of Owerri, Nigeria, Ejimanya, the engineering dean of the Federal University of Technology, Owerri, carries with him a department’s worth of communications, some handwritten, others on disk. He’s delivering them to a man with a PC and an Internet connection, who converts the missives into e-mails and downloads the responses. To Ejimanya, broadband means lugging a big bundle of printed e-mails back with him to the university, which despite being one of the country’s largest and most prestigious engineering schools has no reliable means of connecting to the Internet.

Owerri is a sprawling town hacked out of the jungle in the heart of the oil-rich Niger Delta region formerly known as Biafra. What galls Ejimanya and his colleagues is that Owerri is barely 50 kilometers from the oil city of Port Harcourt and Nigeria’s recently inaugurated 5-Gb/s undersea fiber-optic connection to the outside world. Since the cable landed in the commercial capital of Lagos in December 2001, virtually nothing has been done to hook up the many businesses, schools, and other entities that could benefit from it. And so for Ejimanya and millions of other Nigerians, the high-speed, always-on Internet enjoyed by people in developed countries remains a distant dream.

“If you look at Africa, it’s got wonderful telecommunications facilities around it now and some serious capacity to the outside world,” says William H. Melody, managing director of LIRNE.NET, an international telecommunications policy think tank. “But communication within Africa has not developed, primarily because of the barriers and restrictions protecting special interests”—typically, the government-owned and -operated telephone monopolies.

It’s hard to overestimate the stifling effects of lack of affordable, fast Internet access in a country like Nigeria. Developing countries that are still incapable of providing even one-tenth of the landline telephones, per capita, of a developed country are now faced with a potentially much more serious deficiency, one that they must rectify to integrate themselves into the global economy. Unlike the telephone, which primarily benefited the business and social spheres, the Internet cuts an enormously wider and deeper swath through the educational, medical, intellectual, and cultural spheres of a society.

The Internet is a window to the outside world in places where most international information is scarce. For business people, it can mean the difference between thriving and subsisting. For engineers and researchers, it can propel a career that might otherwise languish in a backwater. For doctors and their patients in a country wracked by AIDS and other scourges, the impact of easy access to good medical information might be tallied in lives saved, or at least prolonged.

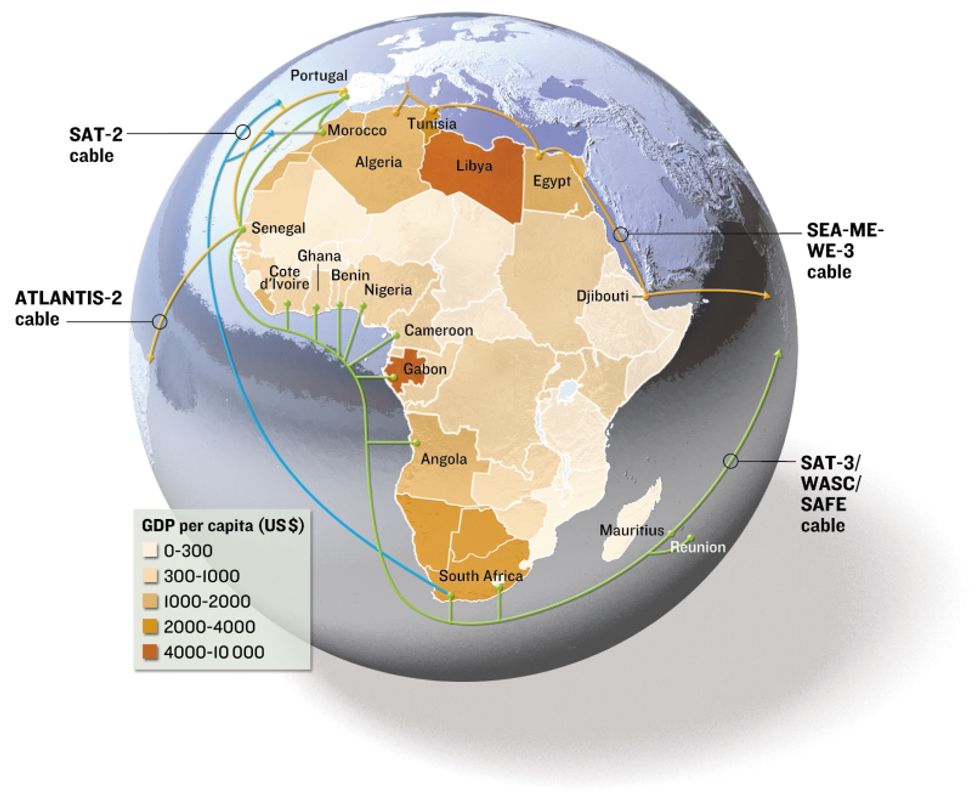

Of course, it’s the same story in developing countries from Laos to Ecuador, Afghanistan to Zambia. But among countries on the wrong side of the so-called digital divide, Nigeria, Africa’s most populous country, now commands attention in a way few others ever have. The reason is a mouthful—the US $650 million, 120-Gb/s South Atlantic Telecommunications Cable No. 3/West African Submarine Cable/South AfricaFar East (SAT-3/WASC/SAFE) Cable.

For many of the sub-Saharan countries where the cable lands, it is the first high-capacity undersea fiber-optic cable to connect them to the rest of the world. Inaugurated into commercial service in April 2002, it was heralded by development officials and others as the beginning of a new chapter in the tortured story of African economic and social development. A happy ending would have Africa skip industrial development and go straight to the Information Age, with customer-service call centers and software-outsourcing businesses providing educated Africans a reason to forgo overseas opportunities and take good paying jobs at home.

But so far, at least, this feel-good story remains unwritten. In the aftermath of 9/11 and the war in Iraq, Africa’s petroleum resources are garnering far more attention than its human resources from countries looking to decrease reliance on Middle Eastern oil. And Nigeria, a straight shot across the Atlantic to the United States and already that country’s fifth leading supplier of oil, seems an attractive alternative. It’s no surprise that when President George W. Bush visited Nigeria last July, a subsidiary of the Shell Group was the only company using the SAT-3 cable in Nigeria.

While Shell employees blaze the Web, ordinary Nigerians, who earn on average less than $1 per day, pay $1 per hour to slog the Net at any one of the hundreds of cybercafes that have sprung up all over the country. For those fees they get a satellite connection that crawls along at less than 2 kb/s during the day, with rare bursts of 28 kb/s late at night.

The average Nigerian does not even know the cable exists, I soon learned during a two-week visit last June to Nigeria and South Africa. I talked to dozens of students, entrepreneurs, government bureaucrats, engineers, and professors to hear how cheap, reliable high-speed Internet access could change their lives for the better and how that potential, for many reasons, remains unfulfilled.

What’s gone wrong? Only a combination of factors could thwart an opportunity as far-reaching as this one. In Nigeria, any accounting has to start with the bureaucracy and incompetence of the state-run telephone monopoly, Nigerian Telecommunications Ltd. (Nitel) and its government overseer, the Nigerian Communications Commission, both in Nigeria’s capital, Abuja. Together, the two organizations hold the authority to create the sort of infrastructure that could make the cable accessible to ordinary Nigerian citizens, students, and businesses, in addition to large multinational corporations.

For now, the cable is perhaps one of the world’s most underutilized technological resources. Designed to handle 5.8 million phone calls simultaneously, the cable traces Portuguese explorer Vasco da Gama’s 15th-century journey from Portugal to India. The SAT-3 section of the cable stretches 14 341 km from Sesimbra, Portugal, to Melkbosstrand, South Africa, passing through eight west African countries along the way. At Melkbosstrand the SAT-3 hooks up with the 13 104-km SAFE portion, which goes through Reunion and Mauritius islands, splitting into two branches that terminate at Cochin, India, and Penang, Malaysia. The cable is owned by a consortium of 36 companies, including many African national telecommunications incumbents, among them Nitel, which contributed nearly $50 million to the cost of the cable, and Telkom SA, Pretoria, South Africa, which chipped in $85 million [see map, "Out of Africa"].

Internet traffic from Africa has increased fivefold over the last four years. But according to Alan Mauldin, senior analyst at TeleGeography, a research division of PriMetrica Inc., of Carlsbad, Calif., a year after the SAT-3 cable was “turned on,” the continent’s total Internet capacity was only 3.226 Gb/s: 1.351 Gb/s between Africa and the United States; 1.875 between Africa and Europe. With more than 13 percent of the world’s population, Africa accounts for only 0.2 percent of the world’s total international Internet capacity.

While TeleGeography pegs usage on the cable at less than 3 percent of its design maximum, the consortium sees the glass fiber as half full. “The usage is already beyond expectations, not only for South Africa, but the whole of western Africa,” says Kobus Stoeder, acting executive, Global Capacity Business, International and Special Markets Segment for Telkom, the administrator of the cable for the consortium. “The only aspect that may be causing some growth stagnation is that in many of these countries, the backhaul network is not quite accessible or may not be fully in place or may not have the capacity to support international access.”

In other words, it’s one thing to lay a fiber-optic undersea cable and bring it to shore; it is quite another to create the internal infrastructure—be it fiber-optic cable or wireless broadband radio nodes—necessary to distribute its bandwidth.

Where it exists at all, the Nigerian telecommunications infrastructure is dilapidated. Even the main switching station of the SAT-3 in Lagos is in poor shape, and it isn’t even two years old.

Accompanied by members Oyewole Funso-Adebayo and Tunde Salihu, I venture to Nitel’s headquarters in the Ikoyi district of Lagos, a hulking black and blue concrete building that looks like a decrepit stadium. The elevators don’t work, so we climb four flights of stairs to the vast, well-appointed but sweltering office of engineer O.B. Okusanya, the deputy general manager of the Lagos International Gateway. Okusanya steps out from behind his huge desk and marches 10 meters down a red carpet to greet us.

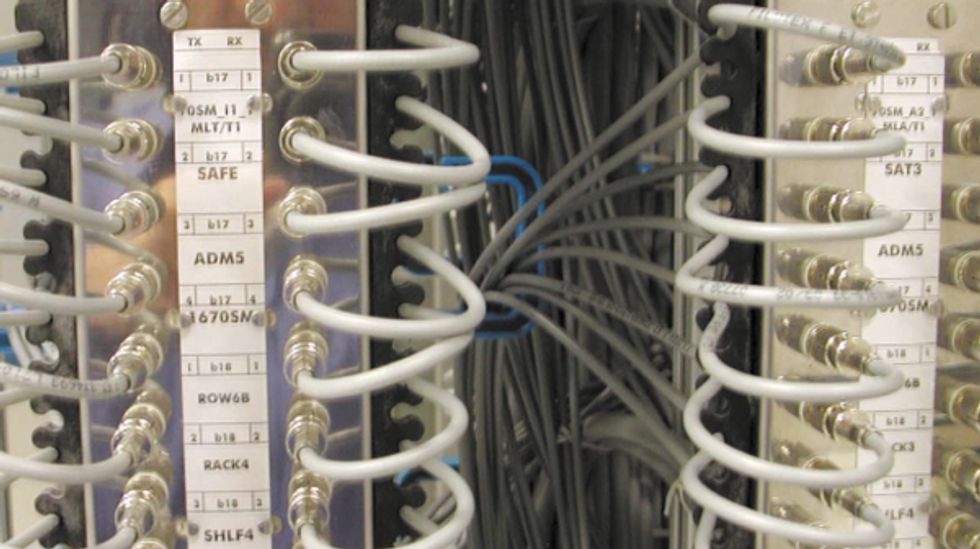

Funso-Adebayo presents a memo from a Nitel administrator authorizing my visit. After a few suspicious glances at me, Okusanya leads us back downstairs to the first floor and down a long, dank hallway lined with broken chairs, blue paint peeling from the walls and ceiling. Finally, we reach the main switching station for the SAT-3 in Nigeria. From here, at least in theory, high-bandwidth connections will feed out to the rest of the country.

As the door creaks open, an engineer abruptly stops playing PacMan on his PC and stands to greet us. A dozen others emerge from around the racks of switching equipment and from an adjacent room where several meter-tall batteries stand in rows like soldiers at attention, ready for action the next time the power fails. This could happen at any moment, thanks to the stunning ineptitude of the National Electric Power Authority, the state-owned power monopoly.

Alcatel SA, Paris, France, brought the cable ashore in December 2001 [see photo, "Networking Nigeria"] and left the Nigerians to their own rather limited devices to get this station up and running. A dearth of funds, equipment, and experienced telecommunications engineers meant the cable didn’t start handling traffic to and from Nigeria until April 2003, two months before I visited.

Two wavelengths are available at Lagos, each 2.5 Gb/s, though only a tiny fraction of one is being used now. Each 2.5-Gb/s bundle is subdivided into 16 synchronous transport mode 1 (STM-1) frames, each capable of handling 155 Mb/s, which can be broken down into smaller units for sale to customers. According to U.I. Nwokocha, chief of transmission, as of last June Nitel was using 78 percent of the capacity of only one of the 13 available STM-1 frames. The sole customer was Shell, which takes advantage of Nigeria’s lone major fiber-optic connection, running from Lagos to Port Harcourt, where Shell has oil and gas production facilities.

The paucity of paying customers for the cable certainly isn’t due to lack of interest; Nwokocha says Nitel gets inquiries every day from companies that want access to the cable. But the same problems that delayed the cable from going into service—lack of funds, equipment, and experienced engineers—has retarded Nitel’s ability to meet demand for high-speed Internet access, not to mention plain old telephone service. In 40 years of monopoly control of Nigeria’s telecommunications, Nitel managed to put in only 500 000 landlines to serve 130 million people. Combine those shortcomings with Nitel’s inability to market its services, and it’s little wonder that the company has blown such a major opportunity.

Realizing that Nitel’s managers were squandering a national resource, the Nigerian government took two steps—it introduced competition, and it brought in management help for Nitel. In 2002, a private company, Lagos-based Globacom, paid $200 million for a license from the Nigerian Communications Commission to become the second national fixed line and wireless operator. The company, which started wireless operations last August, has promised to lay 10 000 km of fiber-optic cable to distribute SAT-3 bandwidth. As the second national operator, Globacom is guaranteed access to SAT-3, but it must negotiate the logistics and pricing of that access with Nitel.

To fix Nitel, the government last year brought in Pentascope International BV, in Amersfoort, the Netherlands, to manage the company. Pentascope is cleaning up the books, trying to collect tens of billions of naira (140 naira is US $1) from delinquent customers, and, according to Nwokocha, planning a promotional campaign around the SAT-3.

For now, though, those few Nigerians who even know about the SAT-3 are frustrated by their inability to get on it. Perhaps no one is more impatient than Aloy Chife, the president and CEO of portal and application service provider Socketworks, based in Lagos, and a former information technology (IT) director of the collapsed Houston-based energy-trading giant Enron Corp.

Chife’s office is decked out with a complete Wi-Fi network and his own satellite connection to a server farm in California, a paltry 256 kb/s for downloads and an even tinier 64-kb/s pipe for uploads. Socketworks doesn’t rely on the inept National Electric Power Authority but on its own 16 diesel power generators. Chife dreams big: starting with his company, he wants to nurture Nigeria’s neophyte IT industries into an outsourcing powerhouse to rival India’s.

“The idea is to leapfrog industrial development. We haven’t even scratched the surface of IT in Nigeria,” says Chife, who also points out that the markets for PCs and peripherals are saturated in the developed world and that Nigeria is still virgin territory.

Unfortunately, the ability of overseas companies to do business in Nigeria hinges on gaining access to the SAT-3, the same fat pipe that could make Socketworks a global competitor. And Nitel has done little to install fiber so businesses in Lagos can get on the broadband bandwagon. Chife had to pay $13 000 to install his own satellite system, including dish, modem, and router, and monthly fees of around $1000. “This country could blossom, but the cost of the Internet is too expensive,” he says.

Cutting those costs won’t be easy. Any attempt to distribute SAT-3 bandwidth will be hindered by a host of challenges, including huge investment overhead. With interest rates for business loans of 25 percent, companies prefer activities that will turn a quick buck—like prepaid wireless, which since 2001 has brought telephone service to more than three million Nigerians through Econet Wireless Nigeria; Globacom; MTN Nigeria Communications Ltd.; and Nitel’s cellular unit, Nigeria Mobile Telecommunications Ltd. (M-Tel).

“There can be explosive growth in the Nigerian telecom market,” says Titi Omo-Ettu, a telecommunications consultant and director of Executive Cyberschuul, an IT training center in Lagos. “But without the commitment to long-term infrastructure development, the whole sector could come crashing down,” as customers lose confidence in their providers’ ability to give them quality service at reasonable prices.

In Lagos, there’s an Internet cafe on just about every block, and in the busy streets, warbling polyphonic ring tones compete with honking horns. To get a taste of the telecommunications situation out in the country, Funso-Adebayo and I hop a flight to Owerri in what used to be called Biafra, where a bloody civil war claimed up to two million lives in the late 1960s.

From the Owerri airport, we share a cab with E.C. Iroakazi, an engineer contracted by M-Tel and MTN to put up cellphone base stations in the area. As the beat-up Peugeot snakes along shattered roads that meander through thick brush broken by the occasional palm tree, we borrow Iroakazi’s cellphone to call Funso-Adebayo’s roommates, some of whom cannot afford rent but still manage to scrounge up enough cash for prepaid mobile service.

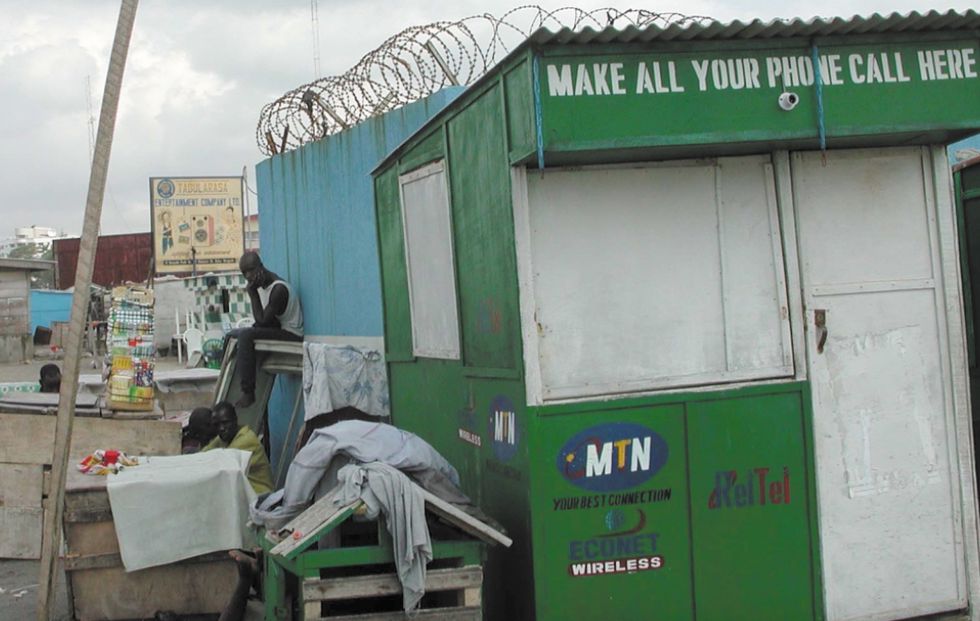

Owerri proper pulsates with people in cars and on motorcycles, others on foot hurrying through the streets, some in and out of sidewalk shacks that offer the use of a mobile phone for 30 naira per minute. Hundreds of people jam the huge market in the town center, while others frequent the numerous, bustling Internet cafes [see photo, "Southwest by West"].

Dawn breaks the next day with Funso-Adebayo knocking on my hostel room door to take me on a walk around suburban Owerri before our scheduled visit to the Federal University of Technology (FUTO) [see photo, "Networking Nigeria"]. As we stroll down the rutted red-mud streets, he points out a house that had been set ablaze by an angry mob just a few years ago after it got out that it was sheltering a cult, known as the Otokoto Seven. After being convicted of ritual killing and trafficking in human flesh, the seven men had been sentenced to death by hanging just months before; three policemen had also been condemned in 2002 after being convicted of killing the informant who had brought the Otokoto’s crimes to light.

My unease intensifies as we approach the ruined house, and the armed policeman standing near its front gate. We get about 10 meters past him and then a shot rings out, a thunderclap that echoes off the surrounding houses with a sharp crack. I nervously peer over my shoulder and then at Funso-Adebayo.

“He’s just showing us that he has bullets in the gun,” he reassures me.

Nigerians like Funso-Adebayo manage to deal with many dangerous, disturbing things over which they have little control: random gunshots, debilitating malarial fevers, constant power outages, endemic corruption, the occasional military dictatorship, and perpetually retarded economic and technological development.

But sometimes the frustration can be too much to bear, especially when there’s someone there to listen.

“As a nation, we are saying we want to catch up, but how can you catch up when your government spends less than 5 percent of GDP on education?” asks Dean Ejimanya when Funso-Adebayo and I finally arrive at the FUTO campus.

In his dark office, which has not had power for two days, Ejimanya explains his improvised e-mail system. He also tells us that each of the 13 departments in the school of engineering has a single computer, which 8000 engineering students use at one point or another to do projects. The one in Ejimanya’s office is partitioned to handle Windows 98, 2000, and Linux. It also holds the student database. And there’s no backup. “If the hard drive goes, that’s it,” Ejimanya sighs.

Given the anger many Delta residents harbor for the oil companies that pump crude out of their region and leave behind nothing but environmental devastation, it would probably be a good public relations move for one of them to invest what amounts to pocket change to buy a few computers for FUTO. Ejimanya says several companies have broken promises to donate computer labs and Internet access. Indeed, a few weeks after I returned from Nigeria, Sola Omole, an official in Nigeria of Chevron Texaco Inc., New Orleans, La., assured me that the company had committed $1 million to build a computer center there. But as of December, it was still just talk.

The introduction of competition in the Nigerian market in the form of both Globacom and a booming, though illegal, trade in voice-over-Internet protocol (VoIP) at cybercafes is already forcing Nitel to compete. In December the company announced that it would take advantage of reduced bandwidth costs afforded by its SAT-3 connection to lower its international calling rates by 50 percent.

The benefits of even the limited competition now starting in Nigeria still elude consumers in Africa’s most potent economy, South Africa. Here telecommunications is dominated by the former state monopoly, Telkom. The International Telecommunication Union, Geneva, Switzerland, estimates that the average South African would have to pay 40 percent of his monthly income for Telkom’s ADSL (asymmetric digital subscriber line) broadband service, while a person in the UK would pay about 1.5 percent of her monthly income for the same bandwidth.

South Africans can blame their lack of affordable high-speed Internet access on their elected government. The government’s partial ownership of Telkom has long stifled efforts to introduce a second national operator to compete in fixed-line voice and data services. Critics contend that the South African government’s ownership position damaged the credibility of its telecommunications policy and regulatory process, and made potential international investors think twice, or not at all, about taking on Telkom in a market rigged in its favor.

The irony is that Telkom would be a formidable competitor even without a public policy warped to its advantage. Much as Nigeria turned to Pentascope for its management expertise, in 1997 the South African government sold 30 percent of Telkom to a strategic investor with managerial control, Thintana Communications LLC, a joint venture of SBC Communications Inc., Austin, Texas, and Telekom Malaysia Berhad, Kuala Lumpur.

In financial terms, the deal has been a bonanza. Under the guidance of an SBC management team, the bloated Telkom shed tens of thousands of jobs to become an efficient, and very profitable, telecommunications dynamo. In March 2003, the South African government cashed in some of its chips by selling off 27.7 percent of the company in an initial public offering, keeping a 39.3 percent stake.

Private investors and the South African government have been richly rewarded. For the fiscal year ended 31 March 2003, basic earnings per share increased 33.5 percent; the price per share has more than doubled since the company went public.

Telkom’s monopoly has had far-reaching consequences for all South Africans. On the one hand, the company has invested billions of rand in Africa’s most technologically sophisticated telecommunications network. On the other hand, the company has kept such tight control of bandwidth that to many ordinary South Africans, Internet access is still as precious as the country’s famous diamonds.

Keeping watch over that valuable resource are the engineers I meet in Melkbosstrand, a quiet seaside suburb about 30 minutes drive from Cape Town. This is where the SAT-2, SAT-3, and SAFE cables all land and feed into Telkom’s cable station. There’s a national switching room here, too, through which flows all of South Africa’s overseas voice and data traffic.

After working together for a decade, Karl Jones and Eddie Croeser, both submarine cable specialists, have an almost marital rapport, and they rattle off facts about the SAT-3 cable like proud parents talking about their very precocious child. The SAT-3, like the SAFE and the SAT-2, has only two fiber pairs conducting all that bandwidth through 191 submerged repeaters spaced about 80 km apart. Jones and Croeser monitor the SAT-3 and SAFE underwater plant—cable, repeaters, and branching units—from this station to check for problems like line breaks [see photos, "Keepers of the Cable" and "Maintenance at Sea"].

Croeser shows me one workstation where he could view all the other cable stations. The fiber-optic cable needs light of a specific wavelength pumped into it to excite the erbium atoms in optical amplifiers, which in turn emit the right wavelength when the erbium atoms fall to a lower energy state. More bits require more power. I asked to see Lagos, which, no surprise, was putting about 1/1000 the amount of power into the line as Melkbosstrand.

Clearly, technology and the money to pay for good engineers and a world-class infrastructure aren’t the problem in South Africa. Cost is. That’s why Christo van der Rheede keeps his 64-kb/s ISDN modem under lock and key.

Van der Rheede is principal of the Silversands Primary School in Kuilsrivier, a township formerly known as Plastic City, in Cape Town, South Africa. He shows me his setup in a locked room at the back of the computer lab. The lab was paid for and installed by a two-year-old project called Khanya. Silversands is just one of some 300 Khanya schools in the Western Cape district that by the end of 2004 will be similarly equipped with new Pentium 4 and Celeron PCs running an array of educational software packages.

Van der Rheede keeps the Internet locked away for good reason. Access costs 400 rand per month (about US $60) and the cost of usage over the bare minimum would have to come out of another Silversands program’s budget. So every day van der Rheede comes to this glorified closet to download e-mail, which he then distributes via the school’s internal network.

For now, the Silversands lab and the school’s limited Internet connectivity are enough to give kids a huge confidence boost and substantially improve their math and science test scores: in 43 Khanya schools surveyed, the number of students earning A’s more than doubled in 2002 over 2001, while the number of those earning passing grades jumped 42 percent. By increasing students’ chances of moving on to university, the computer lab has come to be seen as a community asset, the kind of resource that nonwhite South Africans were denied for so long under apartheid.

Van der Rheede would like nothing better than to get all the kids more access to the Internet. That might happen in the next few months, but students will probably surf the Internet via satellite.

Géza Z. Fagyas, a technology consultant to the Western Cape school district, told me he’s so frustrated with Telkom and its high prices that the Western Cape school district is now negotiating with satellite provider Sentech (Pty) Ltd., Honeydew, South Africa, which has promised a deep discount and a minimum of 64 kb/s to each of the district’s 1500 schools.

“There’s a lot of multimedia that we’d like learners to have, but that’s horrendously expensive on dial-up,” says Fagyas. ADSL is a wonderful alternative, he says, but Telkom restricts traffic volumes as well as bandwidth. Telkom’s DSL is limited to 512 kb/s, for 800 rand (about $120) for business customers per month. Telkom also caps downloads for its 11 500 ADSL customers at 3 GB per month, after which a customer is switched to a slower connection in the 14.428.8-kb/s range. By contrast, business DSL (1.5 Mb/s) in the United States is about $90 per month for three times the bandwidth and no volume restrictions. Prices in a few countries, such as Korea and Canada, are even lower.

Such high pricing in the face of dramatically reduced bandwidth costs is “almost criminal,” according to LIRNE.NET’s Melody, who is also a professor at the Technical University of Denmark. “It is crippling for these people. And it’s not just a failure to take advantage of an opportunity to develop a sector which can then develop the whole economy, they’re actually destroying value,” he contends. “Education is a good case in point. In order to get any minimal connections at all, people have to make enormous cutbacks in other things they do. The whole business of e-education turns out to be a bit of a farce under these conditions.”

Wally Beelders, Telkom managing executive for international and special market services, counters that bandwidth prices in Africa will never be in the same league as those in Europe and the United States. “It is all a question of scales of economy,” he says. “In Europe and the U.S.A. there are hundreds of millions of users who share the high-cost layout of submarine cables, whereas in Africa a much smaller number have to pay for vast infrastructure to get connected to the Northern Hemisphere.”

Telkom’s restrictions cost users money in other ways. Most notably, it blocks the use of VoIP services. Across Africa and around the globe, businesses and consumers have been finding ways to turn otherwise expensive telephone calls into data packets, which can then be transmitted over the Internet at much lower cost or even free. But as South Africa’s telecommunications monopoly, Telkom is the only company licensed to carry voice communications, and current legislation prohibits Internet service providers and value-added network services companies from providing VoIP services. Such services could provide stiff competition to Telkom by driving down costs for both local and international calls, a potential boon for companies trying to imitate the international outsourcing success of India.

Telkom can hardly be blamed for taking advantage of the monopoly powers granted by the South African government. The five-year government-mandated monopoly position was supposed to end on 7 May 2002, and with it a number of restrictions on competition, but the communications minister has so far refused to sign the necessary documents. This prodigious cash cow has left the government with a clear conflict of interest. How can the government regulate a company in which it has a vested, and very lucrative, interest and at the same time license a second national operator, in which it will own at least a 30 percent stake, to compete with that company?

The short answer is: not very well.

In the last year, the South African ministry of communications twice rejected consortia that were vying to be the majority shareholder in the second national operator the ministry was supposed to license three years ago, claiming that their international partners didn’t have the wherewithal or commitment to compete with Telkom. That left the three other shareholders, two of which have already made substantial infrastructure investments, swinging in the wind: Nexus Connexion in Marshalltown, a holding company that represents traditionally disadvantaged (nonwhite) South African investors; Transtel in Joubert Park, a unit of the state transportation monopoly; and Eskom Enterprises (Pty) Ltd. in Johannesburg, a unit of the state energy monopoly.

Transtel and Eskom have between them invested more than 1 billion rand ($150 million) in building fiber-optic infrastructure along railway and power lines in anticipation of operations beginning last year. Their investment lies idle, a cost in terms of cash and lost opportunity.

Now those investments might just pay off. After months of indecision, at the beginning of January, the ministry of communications gave two groups it had previously rejected, CommuniTel and Two Consortium, each a 13 percent stake in the second national operator. The South African government will hold onto the remaining 25 percent stake. The new company is expected to launch fixed-line, Internet, and cellphone service sometime this year.

Even as South Africa launches a second national operator, the ultimate effect on the market could be minimal at best, says Melody. History shows managed duopolies don’t improve a country’s telecommunications landscape, he says, especially when the government is a significant owner of both companies.

Still, it’s important to remember that the new South Africa wrote its first telecommunications law in 1996. Given time, many South Africans believe market liberalization will eventually come to a country that has undergone a remarkable transformation in the one decade since its first democratic elections.

Indeed, fast, affordable telecommunications is the linchpin for the economic and social transformation of Africa as a whole. Good telecommunications can make other basic services—health care, finance, clean water, electricity, housing, transportation—run more efficiently and cost effectively. But before those benefits can ripple through the broader economy, serious reforms must take hold all over the continent.

“What’s happening in Africa isn’t any different than what’s happened everywhere else,” Melody concludes. “Very often it takes a decade or more for people to learn from good and bad experiences and to gradually bring about and effectively implement the necessary policy changes.”