Do You Need a Blockchain?

This interactive will tell you if a blockchain can solve your problem

According to a study released this July by Juniper Research, more than half the world’s largest companies are now researching blockchain technologies with the goal of integrating them into their products. Projects are already under way that will disrupt the management of health care records, property titles, supply chains, and even our online identities. But before we remount the entire digital ecosystem on blockchain technology, it would be wise to take stock of what makes the approach unique and what costs are associated with it.

Blockchain technology is, in essence, a novel way to manage data. As such, it competes with the data-management systems we already have. Relational databases, which orient information in updatable tables of columns and rows, are the technical foundation of many services we use today. Decades of market exposure and well-funded research by companies like Oracle Corp. have expanded the functionality and hardened the security of relational databases. However, they suffer from one major constraint: They put the task of storing and updating entries in the hands of one or a few entities, whom you have to trust won’t mess with the data or get hacked.

Blockchains, as an alternative, improve upon this architecture in one specific way—by removing the need for a trusted authority. With public blockchains like Bitcoin and Ethereum, a group of anonymous strangers (and their computers) can work together to store, curate, and secure a perpetually growing set of data without anyone having to trust anyone else. Because blockchains are replicated across a peer-to-peer network, the information they contain is very difficult to corrupt or extinguish.

This feature alone is enough to justify using a blockchain if the intended service is the kind that attracts censors. A version of Facebook built on a public blockchain, for example, would be incapable of censoring posts before they appeared in users’ feeds, a feature that Facebook reportedly had under development while the company was courting the Chinese government in 2016.

I Want a Blockchain!

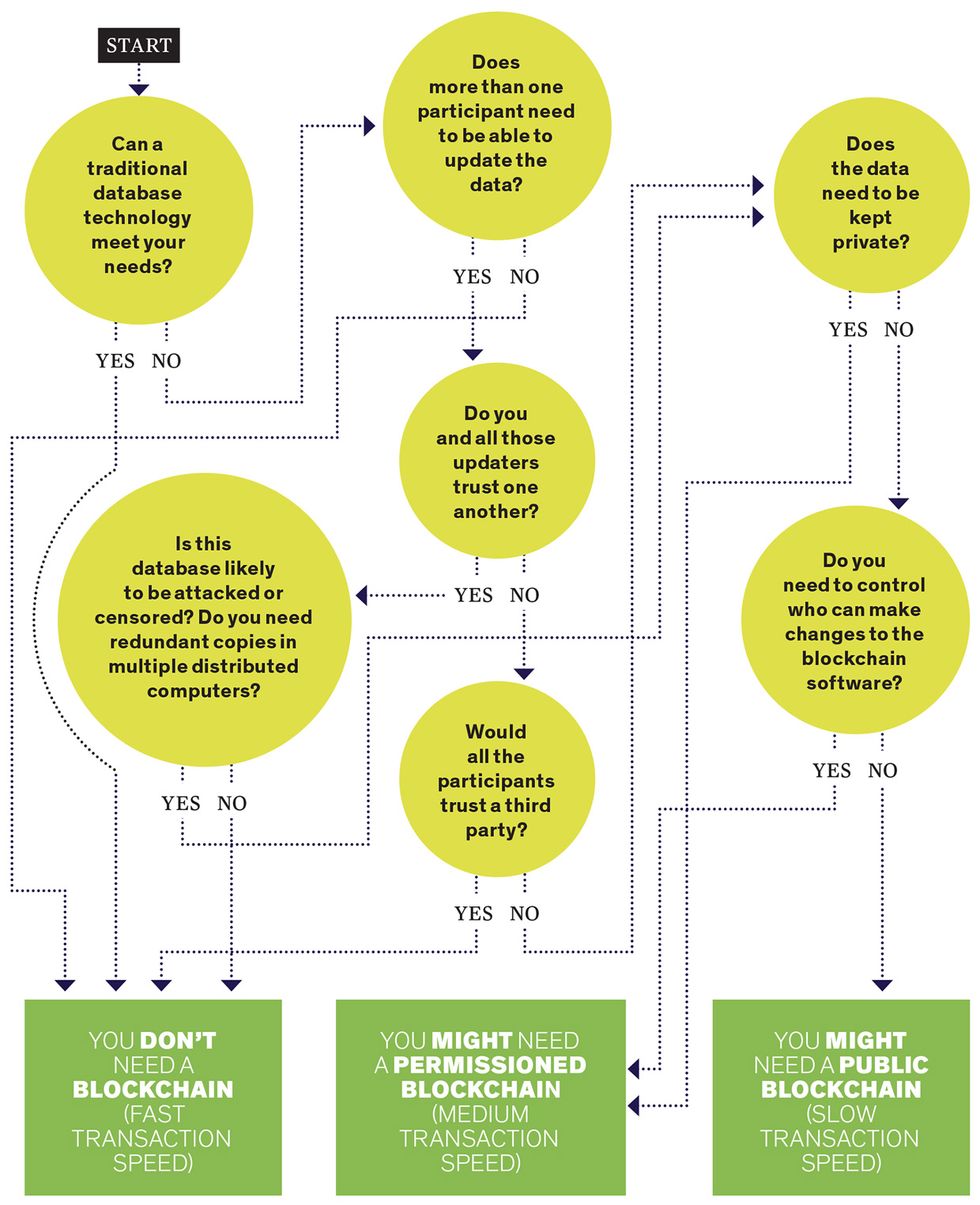

Do you really need a blockchain? Asking yourself a handful of the questions in this interactive can set you on the right path to an answer. You’ll note that there are more reasons not to use a blockchain than there are reasons to do so. And if you do choose a blockchain, be ready for slower transaction speeds.

To see a version of this as a decision tree, scroll to the bottom of the page.

However, removing the need for trust comes with limitations. Public blockchains are slower and less private than traditional databases, precisely because they have to coordinate the resources of multiple unaffiliated participants. To import data onto them, users often pay transaction fees in amounts that are constantly changing and therefore difficult to predict. And the long-term status of the software is unpredictable as well. Just as no one person or company manages the data on a public blockchain, no one entity updates the software. Rather, a whole community of developers contributes to the open-source code in a process that, in Bitcoin at least, lacks formal governance.

Given the costs and uncertainties of public blockchains, they’re not the answer to every problem. “If you don’t mind putting someone in charge of a database…then there’s no point using a blockchain, because [the blockchain] is just a more inefficient version of what you would otherwise do,” says Gideon Greenspan, the CEO of Coin Sciences, a company that builds technologies on top of both public and permissioned blockchains.

With this one rule, you can mow down quite a few blockchain fantasies. Online voting, for example, has inspired many well-intentioned blockchain developers, but it probably does not stand to gain much from the technology.

“I find myself debunking a blockchain voting effort about every few weeks,” says Josh Benaloh, the senior cryptographer at Microsoft Research. “It feels like a very good fit for voting, until you dig a couple millimeters below the surface.”

Benaloh points out that tallying votes on a blockchain doesn’t obviate the need for a central authority. Election officials will still take the role of creating ballots and authenticating voters. And if you trust them to do that, there’s no reason why they shouldn’t also record votes.

The headaches caused by open blockchains—the price volatility, low throughput, poor privacy, and lack of governance—can be alleviated, in part, by tweaking the structure of the technology, specifically by opting for a variation called a permissioned ledger.

In a permissioned ledger, you avoid having to worry about trusting people, and you still get to keep some of the benefits of blockchain technology. The software restricts who can amend the database to a set of known entities. This one alteration removes the economic component from a blockchain. In a public blockchain, miners (the parties adding new data to the blockchain) neither know nor trust one another. But they behave well because they are paid for their work.

By contrast, in a permissioned blockchain, the people adding data follow the rules not because they are getting paid but because other people in the network, who know their identities, hold them accountable.

Removing miners also improves the speed and data-storage capacity of a blockchain. In a public network, a new version of the blockchain is not considered final until it has spread and received the approval of multiple peers. That limits how big new blocks can be, because bigger blocks would take longer to get around. As of July, Bitcoin can handle a maximum of 7 transactions per second. Ethereum tops out at around 20 transactions per second.

When blocks are added by fewer, known entities, they can hold more data without slowing things down or threatening the security of the blockchain. Greenspan of Coin Sciences claims that MultiChain, one of his company’s permissioned blockchain products, is capable of processing 1,000 transactions per second. But even this pales in comparison with the peak throughput of credit card transactions handled by Visa—an amount The Washington Post reports as being 10 times that number.

As the name perhaps suggests, permissioned ledgers also enable more privacy than public blockchains. The software restricts who can access a permissioned blockchain, and therefore who can see it. It’s not a perfect solution; you’re still revealing your data to those within the network. You wouldn’t, for example, want to run a permissioned blockchain with your competitors and use it to track information that gives away trade secrets. But permissioned blockchains may enable applications where data needs to be shielded only from the public at large.

“If you are willing for the activity on the ledger to be visible to the participants but not to the outside world, then your privacy problem is solved,” says Greenspan.

Finally, using a permissioned blockchain solves the problem of governance. Bitcoin is a perfect demonstration of the risks that come with building on top of an open-source blockchain project. For two years, the developers and miners in Bitcoin have waged a political battle over how to scale up the system. This summer, the sparring went so far that one faction split off to form its own version of Bitcoin. The fight demonstrated that it’s impossible to say with any certainty what Bitcoin will look like in the next month, year, or decade—or even who will decide that. And the same goes for every public blockchain.

With permissioned ledgers, you know who’s in charge. The people who update the blockchain are the same people who update the code. How those updates are made depends on what governance structure the participants in the blockchain collectively agree to.

Public blockchains are a tremendous improvement on traditional databases if the things you worry most about are censorship and universal access. Under those circumstances, it might just be worth it to build on a technology that sacrifices cost, speed, privacy, and predictability. And if that sacrifice isn’t worth it, a more limited version of Satoshi Nakamoto’s original blockchain may balance out your needs. But you should also consider the possibility that you don’t need a blockchain at all.