Laser-based radar offers a lot to smart cars, but it's too bulky and expensive for anything but Google's cost-be-damned robocar. Things would be different if you could make it small and cheap.

That's what Behnam Behroozpour, a graduate student, and his colleagues at the University of California at Berkeley propose to do. They are trying to pack the entire 3-D imaging system, known as LIDAR, into a solid-state package that could easily fit inside a smart phone or a game-playing wand.

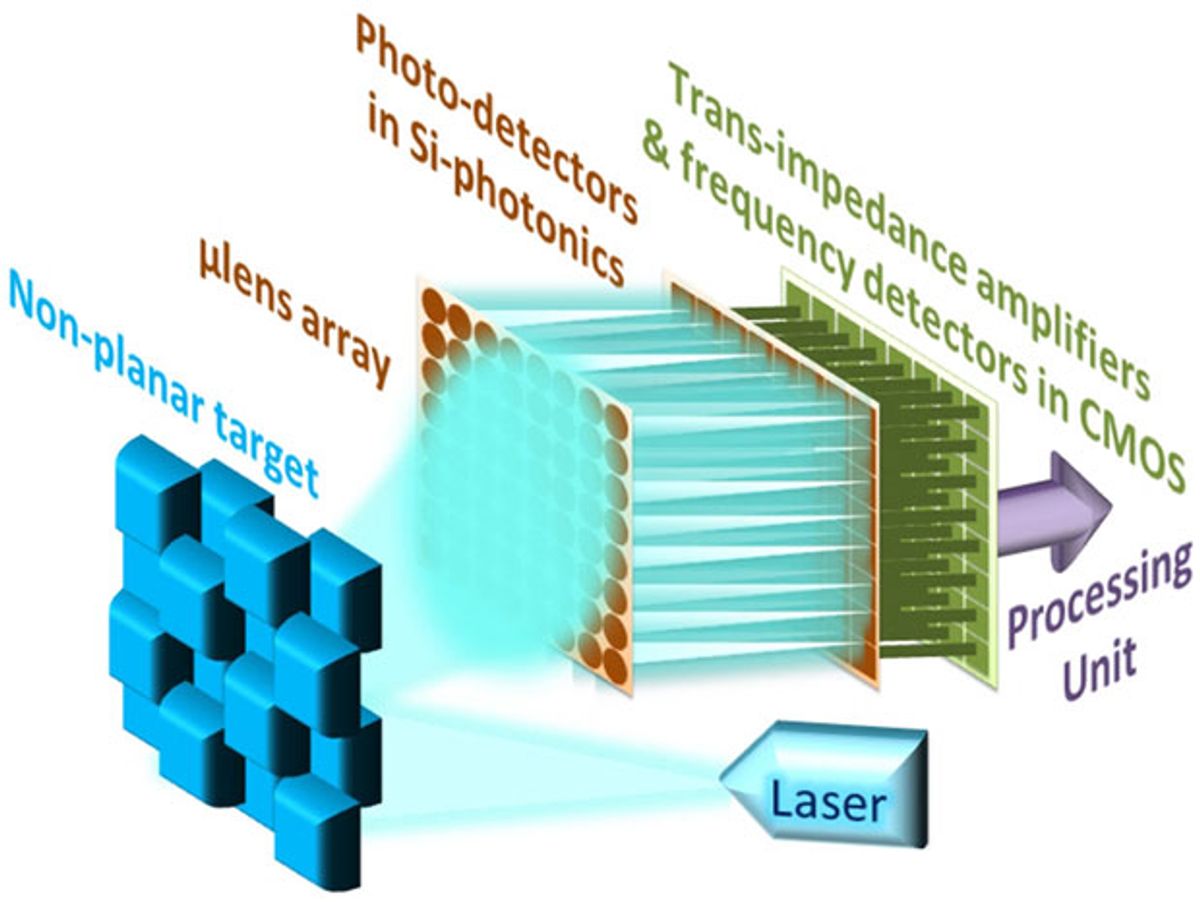

"We have in mind a 3 millimeter by 3 millimeter silicon chip, with the photonics integrated; a CMOS chip for the electronics; and a VCSEL [vertical cavity] laser, also as a chip," he tells Spectrum. He adds that he and his colleagues have tested the individual parts but are only now beginning to put them all together. Right now, the experimental system is about as big as a Microsoft Kinect box.

He doesn't yet know the precise specs of the integrated system, but in its first iteration the beam should be able to see about 10 meters distance. Although that's not enough for some automotive applications, the Berkeley team is already thinking about how to reach out 30 or even 100 meters.

LIDAR works by sending out a beam and timing the return of its reflection. To guard against mistaking ambient light for part of that reflection, you can systematically vary the power of the beam; better yet, you can vary the frequency. Such frequency modulation is managed by tiny vibrating MEMS mirrors fabricated right in the silicon chip.

The researchers electronically tune the frequency to exploit the natural vibration, or resonance, of the mirrors. This trick saves a lot of power. "It's more complicated, but you are gaining in the signal-to-noise ratio," Behroozpour says. Noise, in this case, comes from stray light rays that might be mistaken for reflections.

Today's robotic cars depend on a lot of overlapping sensors—lasers, radar, ultrasound, standard cameras, stereocameras, GPS, inertial guidance, even WiFi. Radar is now the key element, in part because it can work in any light and in any weather, in part because the size and cost has come down a lot, thanks to the aerospace industry. But if you could scatter cheap LIDAR sets around the car, in inconspicuous places, you could take advantage of its high resolution and capacity for orderly, focused scanning.

To do that, you have to cut the cost. Google Car's set is reported to cost US $70 000. Behroozpour says he expects his first integrated system to cost a few hundred dollars. Even that might be a bit pricey for smartphones and game controllers; then again, it isn't bad for the first-ever price tag of a solid-state system.

And in the solid-state world, cost follows a familiar trajectory: whatever goes down, goes way down.

Philip E. Ross is a senior editor at IEEE Spectrum. His interests include transportation, energy storage, AI, and the economic aspects of technology. He has a master's degree in international affairs from Columbia University and another, in journalism, from the University of Michigan.