As our cars turn into rolling supercomputers, it’s easy to forget one of their emerging electronic needs: managing massive data flows within the car. In a self-driving car, sensors should throw off some 4 terabytes a day.

“Connectivity is one of the missing elements,” says Micha Risling, head of the automotive business at Valens, a fabless semiconductor company in Israel. “On one hand you have the Nvidias of this world—the companies that offer processing solutions—and, on the other hand, there are the companies that offer sensors, cameras, even displays. We provide the connectivity.”

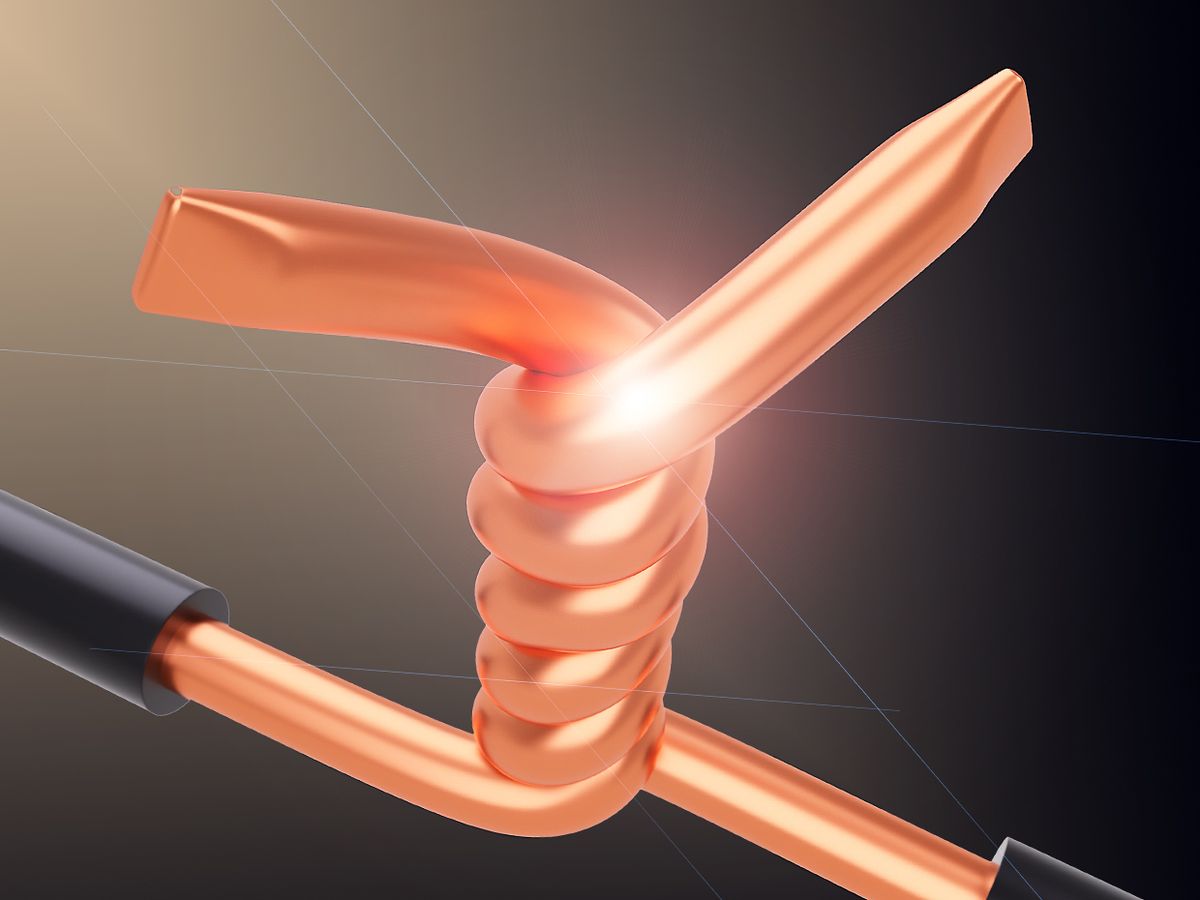

And because Valen’s method involves just a twisted pair of copper wires, a single cable can replace several. That’s an improvement—even over the futuristic alternative, which is to use fiberoptic cable. Carmakers would rather put off that wrenching change and just extend the Age of Copper.

Valens invented HDBaseT (a single cable that allows transmission of ultra-high-definition video & audio, Ethernet, controls, USB and up to 100 watts of power) in the 2000s, then promulgated it as a standard together with LG, Samsung and Sony. Today the HDBaseT Alliance numbers around 190 companies. Most of the early adopters were in the consumer electronics business, but now the members include such automotive players as GM, Daimler and Delphi. Last year, Daimler said it would incorporate the Valens system into cars in “the near future.”

The original point was to use signal processing to push high-definition video, audio and other bandwidth hogs further than the several meters that is possible with the old HDMI standard. HDBaseT stretches out as far as 100 meters.

That extra reach may not matter much to low-end consumers, who just need to hook a disc player to an HD television set. But it matters in large-area networks of the sort you see in corporations, universities and other high-end users. And it really matters inside a car, where all the close-packed electronics create a tight fit.

The rising tide of sensors, computers and actuators is filling in the last remaining empty holes in a car. Designers typically put a lot of the power-hungry computers in the back of vehicles, so the interconnects need to extend to them. The HDBaseT standard makes it possible to do that simply by snaking a single wire through a tight spot in a door assembly or a floor panel.

There’s another major issue the copper cable solves: “You’ve got to make sure the emissions won’t influence other cables and solutions next to you,” Risling says. “And you need to know how much noise you can tolerate without killing your performance. Other technologies, in a way, gave up, which is why they are using shielded cable—expensive, limited in distance and performance. We use special signal processing instead.”

That processing monitors electromagnetic interference—if necessary, using anti-noise to cancel it out. And because HDBaseT extracts information and encapsulates it into packets, it can send those packets over a channel efficiently. That lets it manage high data rates at frequencies low enough to be rather immune to interference—all with just an unshielded pair of copper wires.

True, that savings in the wire is offset by the extra cost of the chipset. The reason HDBaseT isn’t used to connect a low-end disc player to a TV is that the chips cost about as much as the player. But today’s car is a true local area network, even if all you consider is the infotainment system. Throw in the data flowing from cameras, radars, lidar sensors, brakes, GPS and other smart-car doodads, and you’ve got the highest-end system you’re likely to find this side of a fighter jet.

Philip E. Ross is a senior editor at IEEE Spectrum. His interests include transportation, energy storage, AI, and the economic aspects of technology. He has a master's degree in international affairs from Columbia University and another, in journalism, from the University of Michigan.