Building Your Own Cellphone Network Can Be Empowering, and Also Problematic

Neglected by telecom providers for years, a Mexican village created its own cell service. And then Movistar came calling

During the summer of 2013, news reports recounted how a Mexican pueblo launched its own do-it-yourself cellphone network. The people of Talea de Castro, population 2,400, created a mini-telecom company, the first of its kind in the world, without help from the government or private companies. They built it after Mexico’s telecommunications giants failed to provide mobile service to the people in the region. It was a fascinating David and Goliath story that pitted the country’s largest corporation against indigenous villagers, many of whom were Zapotec-speaking subsistence farmers with little formal education.

The reports made a deep impression on me. In the 1990s, I’d spent more than two years in Talea, located in the mountains of Oaxaca in southern Mexico, working as a cultural anthropologist.

Reading about Talea’s cellular network inspired me to learn about the changes that had swept the pueblo since my last visit. How was it that, for a brief time, the villagers became international celebrities, profiled by USA Today, BBC News, Wired, and many other media outlets? I wanted to find out how the people of this community managed to wire themselves into the 21st century in such an audacious and dramatic way—how, despite their geographic remoteness, they became connected to the rest of the world through the wondrous but unpredictably powerful magic of mobile technology.

I naively thought it would be the Mexican version of a familiar plot line that has driven many Hollywood films: Small-town men and women fearlessly take on big, bad company. Townspeople undergo trials, tribulations, and then…triumph! And they all lived happily ever after.

I discovered, though, that Talea’s cellphone adventure was much more complicated—neither fairy tale nor cautionary tale. And this latest phase in the pueblo’s centuries-long effort to expand its connectedness to the outside world is still very much a work in progress.

Sometimes it’s easy to forget that 2.5 billion people—one-third of the planet’s population—don’t have cellphones. Many of those living in remote regions want mobile service, but they can’t have it for reasons that have to do with geography, politics, or economics.

In the early 2000s, a number of Taleans began purchasing cellphones because they traveled frequently to Mexico City or other urban areas to visit relatives or to conduct business. Villagers began petitioning Telcel and Movistar, Mexico’s largest and second-largest wireless operators, for cellular service, and they became increasingly frustrated by the companies’ refusal to consider their requests. Representatives from the firms claimed that it was too expensive to build a mobile network in remote locations—this, in spite of the fact that Telcel’s parent company, América Móvil, is Mexico’s wealthiest corporation. The board of directors is dominated by the Slim family, whose patriarch, Carlos Slim, is among the world’s richest men.

But in November 2011, an opportunity arose when Talea hosted a three-day conference on indigenous media. Kendra Rodríguez and Abrám Fernández, a married couple who worked at Talea’s community radio station, were among those who attended. Rodríguez is a vivacious and articulate young woman who exudes self-confidence. Fernández, a powerfully built man in his mid-thirties, chooses his words carefully. Rodríguez and Fernández are tech savvy and active on social media. (Note: These names are pseudonyms.)

Also present were Peter Bloom, a U.S.-born rural-development expert, and Erick Huerta, a Mexican lawyer specializing in telecommunications policy. Bloom had done human rights work in Nigeria in rural areas where “it wasn’t possible to use existing networks because of security concerns and lack of finances,” he explains. “So we began to experiment with software that would enable communication between phones without relying upon any commercial companies.” Huerta had worked with the United Nations’ International Telecommunication Union.

The two men founded Rhizomatica, a nonprofit focused on expanding cellphone service in indigenous areas around the world. At the November 2011 conference, they approached Rodríguez and Fernández about creating a community cell network in Talea, and the couple enthusiastically agreed to help.

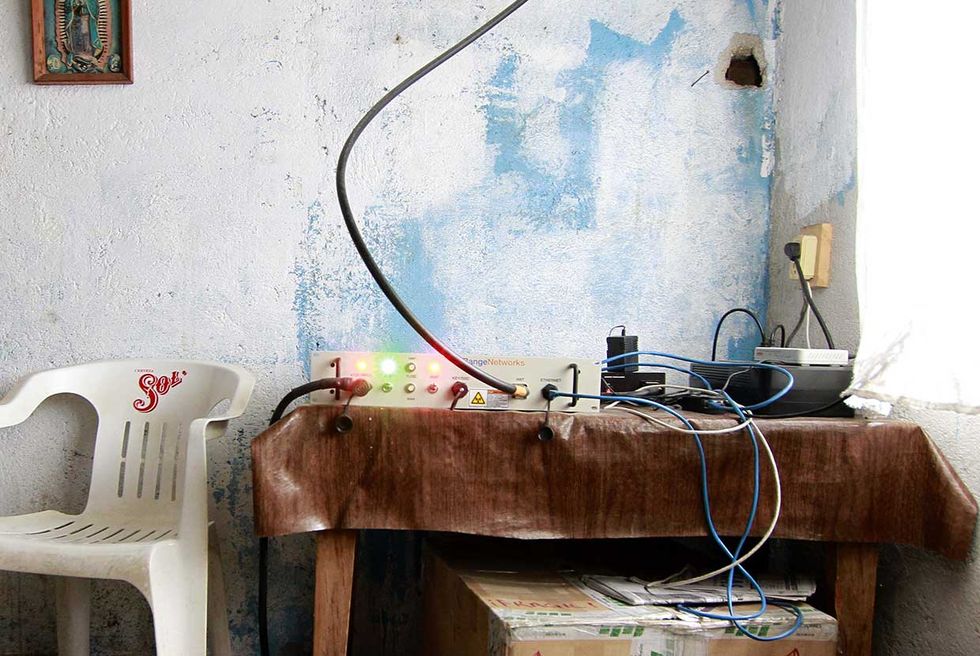

In 2012, Rhizomatica assembled a ragtag team of engineers and hackers to work on the project. They decided to experiment with open-source software called OpenBTS—Open Base Transceiver Station—which allows cell phones to communicate with each other if they are within range of a base station. Developed by David Burgess and Harvind Samra, cofounders of the San Francisco Bay Area startup Range Networks, the software also allows networked phones to connect over the Internet using VoIP, or Voice over Internet Protocol. OpenBTS had been successfully deployed at Burning Man and on Niue, a tiny Polynesian island nation.

Bloom’s team began adapting OpenBTS for Talea. The system requires electrical power and an Internet connection to work. Fortunately, Talea had enjoyed reliable electricity for nearly 40 years and had gotten Internet service in the early 2000s.

In the meantime, Huerta pulled off a policy coup: He convinced federal regulators that indigenous communities had a legal right to build their own networks. Although the government had granted telecom companies access to nearly the entire radio-frequency spectrum, small portions remained unoccupied. Bloom and his team decided to insert Talea’s network into these unused bands. They would become digital squatters.

As these developments were under way, Rodríguez and Fernández were hard at work informing Taleans about the opportunity that lay before them. Rodríguez used community radio to pique interest among her fellow villagers. Fernández spoke at town hall meetings and coordinated public information sessions at the municipal palace. Soon they had support from hundreds of villagers eager to get connected. Eventually, they voted to invest 400,000 pesos (approximately US $30,000) of municipal funding for equipment to build the cellphone network. By doing so, the village assumed a majority stake in the venture.

In March 2013, the cellphone network was finally ready for a trial run. Volunteers placed an antenna near the town center, in a location they hoped would provide adequate coverage of the mountainside pueblo. As they booted up the system, they looked for the familiar signal bars on their cellphone screens, hoping for a strong reception.

The bars light up brightly—success!

The team then walked through the town’s cobblestone streets in order to detect areas with poor reception. As they strolled up and down the paths, they heard laughter and shouting from several houses. People emerged from their homes, stunned.

“We’ve got service!” exclaimed a woman in disbelief.

“It’s true, I called the state capital!” cried a neighbor.

“I just connected to my son in Guadalajara!” shouted another.

Although Rodríguez, Fernández, and Bloom knew that many Taleans had acquired cellphones over the years, they didn’t realize the extent to which the devices were being used every day—not for communications but for listening to music, taking photos and videos, and playing games. Back at the base station, the network computer registered more than 400 cellphones within the antenna’s reach. People were already making calls, and the number was increasing by the minute as word spread throughout town. The team shut down the system to avoid an overload.

As with any experimental technology, there were glitches. Outlying houses had weak reception. Inclement weather affected service, as did problems with Internet connectivity. Over the next six months, Bloom and his team returned to Talea every week, making the 4-hour trip from Oaxaca City in a red Volkswagen Beetle.

Their efforts paid off. The community network proved to be immensely popular, and more than 700 people quickly subscribed. The service was remarkably inexpensive: Local calls and text messages were free, and calls to the United States were only 1.5 cents per minute, approximately one-tenth of what it cost using landlines. For example, a 20-minute call to United States from the town’s phone kiosk might cost a campesino a full day’s wages.

Initially, the network could handle only 11 phone calls at a time, so villagers voted to impose a 5-minute limit to avoid overloads. Even with these controls, many viewed the network as a resounding success. And patterns of everyday life began to change, practically overnight: Campesinos who walked 2 hours to get to their corn fields could now phone family members if they needed provisions. Elderly women collecting firewood in the forest had a way to call for help in case of injury. Youngsters could send messages to one another without being monitored by their parents, teachers, or peers. And the pueblo’s newest company—a privately owned fleet of three-wheeled mototaxis—increased its business dramatically as prospective passengers used their phones to summon drivers.

Soon other villages in the region followed Talea’s lead and built their own cellphone networks—first, in nearby Zapotec-speaking pueblos and later, in adjacent communities where Mixe and Mixtec languages are spoken. By late 2015, the villages had formed a cooperative, Telecomunicaciones Indígenas Comunitarias, to help organize the villages’ autonomous networks. Today TIC serves more than 4,000 people in 70 pueblos.

But some in Talea de Castro began asking questions about management and maintenance of the community network. Who could be trusted with operating this critical innovation upon which villagers had quickly come to depend? What forms of oversight would be needed to safeguard such a vital part of the pueblo’s digital infrastructure? And how would villagers respond if outsiders tried to interfere with the fledgling network?

On a chilly morning in May 2014, Talea’s Monday tianguis, or open-air market, began early and energetically. Some merchants descended upon the mountain village by foot alongside cargo-laden mules. But most arrived on the beds of clattering pickup trucks. By daybreak, dozens of merchants were displaying an astonishing variety of merchandise: produce, fresh meat, live farm animals, eyeglasses, handmade huaraches, electrical appliances, machetes, knockoff Nike sneakers, DVDs, electronic gadgets, and countless other items.

Hundreds of people from neighboring villages streamed into town on this bright spring morning, and the plaza came alive. By midmorning, the pueblo’s restaurants and cantinas were overflowing. The tianguis provided a welcome opportunity to socialize over coffee or a shot of fiery mezcal.

As marketgoers bustled through the streets, a voice blared over the speakers of the village’s public address system, inviting people to attend a special event—the introduction of a new, commercial cellphone network. Curious onlookers congregated around the central plaza, drawn by the sounds of a brass band.

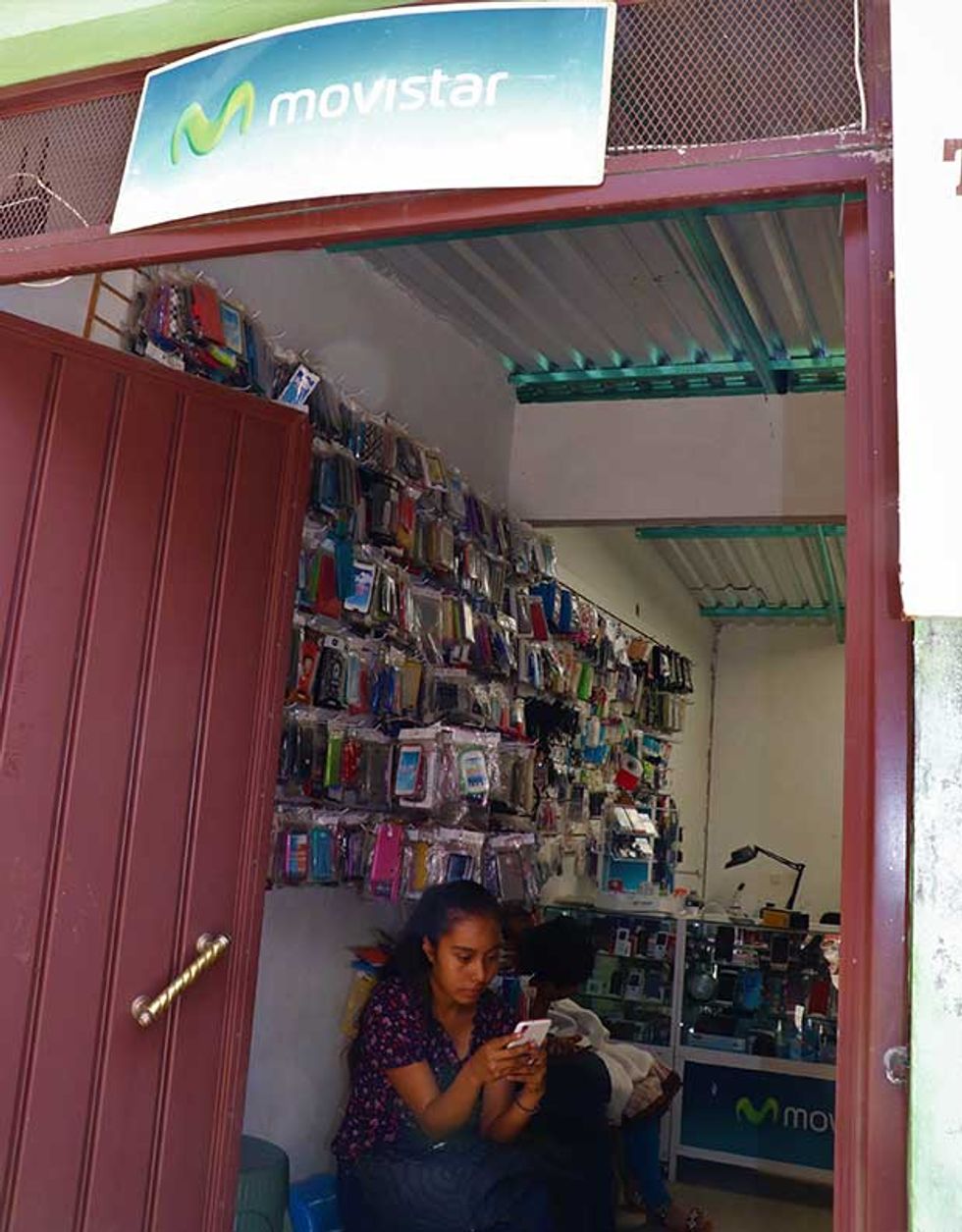

As music filled the air, two young men in polo shirts set up inflatable “sky dancers,” then assembled tables in front of the stately municipal palace. The youths draped the tables with bright blue tablecloths, each imprinted with the logo of Movistar, Mexico’s second-largest wireless provider. Six men then filed out of the municipal palace and sat at the tables, facing the large audience.

What followed was a ceremony that was part political rally, part corporate event, part advertisement—and part public humiliation. Four of the men were politicians affiliated with the authoritarian Institutional Revolutionary Party, which has dominated Oaxaca state politics for a century. They were accompanied by two Movistar representatives. A pair of young, attractive local women stood nearby, wearing tight jeans and Movistar T-shirts.

The politicians and company men had journeyed to the pueblo to inaugurate a new commercial cellphone service, called Franquicias Rurales (literally, “Rural Franchises”). As the music faded, one of the politicians launched a verbal attack on Talea’s community network, declaring it to be illegal and fraudulent. Then the Movistar representatives presented their alternative plan.

A cellphone antenna would soon be installed to provide villagers with Movistar cellphone service—years after a group of Taleans had unsuccessfully petitioned the company to do precisely that. Movistar would rent the antenna to investors, and the franchisees would sell service plans to local customers in turn. Profits would be divided between Movistar and the franchise owners.

The grand finale was a fiesta, where the visitors gave away cheap cellphones, T-shirts, and other swag as they enrolled villagers in the company’s mobile-phone plans.

The Movistar event came at a tough time for the pueblo’s network. From the beginning, it had experienced technical problems. The system’s VoIP technology required a stable Internet connection, which was not always available in Talea. As demand grew, the problems continued, even after a more powerful system manufactured by the Canadian company Nutaq/NuRAN Wireless was installed. Sometimes, too many users saturated the network. Whenever the electricity went out, which is not uncommon during the stormy summer months, technicians would have to painstakingly reboot the system.

In early 2014, the network encountered a different threat: opposition from the community. Popular support for the network was waning amidst a growing perception that those in charge of maintaining the network were mismanaging the enterprise. Soon, village officials demanded that the network repay the money granted by the municipal treasury. When the municipal government opted to become Talea’s Movistar franchise owner, they used these repaid funds to pay for the company’s antenna. The homegrown network lost more than half of its subscribers in the months following the company’s arrival. In March 2019, it shut down for good.

No one forced Taleans to turn their backs on the autonomous cell network that had brought them international fame. There were many reasons behind the pueblo’s turn to Movistar. Although the politicians who condemned the community network were partly responsible, the cachet of a globally recognized brand also helped Movistar succeed. The most widely viewed television events in the pueblo (as in much of the rest of the world) are World Cup soccer matches. As Movistar employees were signing Taleans up for service during the summer of 2014, the Mexican national soccer team could be seen on TV wearing jerseys that prominently featured the telecom company’s logo.

But perhaps most importantly, young villagers were drawn to Movistar because of a burning desire for mobile data services. Many teenagers from Talea attended high school in the state capital, Oaxaca City, where they became accustomed to the Internet and all that it offers.

Was Movistar’s goal to smash an incipient system of community-controlled communication, destroy a bold vision for an alternative future, and prove that villagers are incapable of managing affairs themselves? It’s hard to say. The company’s goals were probably motivated more by long-term financial objectives: to increase market share by extending its reach into remote regions.

And yet, despite the demise of Talea’s homegrown network, the idea of community-based telecoms had taken hold. The pueblo had paved the way for significant legal and regulatory changes that made it possible to create similar networks in nearby communities, which continue to thrive.

The people of Talea have long been open to outside ideas and technologies, and have maintained a pragmatic attitude and a willingness to innovate. The same outlook that led villagers to enthusiastically embrace the foreign hackers from Rhizomatica also led them to give Movistar a chance to redeem itself after having ignored the pueblo’s earlier appeals. In this town, people greatly value convenience and communication. As I tell students at my university, located in the heart of Silicon Valley, villagers for many years have longed to be reliably and conveniently connected to each other—and to the rest of the world. In other words, Taleans want cellphones because they want to be like you.

This article is based on excerpts from Connected: How a Mexican Village Built Its Own Cell Phone Network (University of California Press, 2020).

About the Author

Roberto J. González is chair of the anthropology department at San José State University.