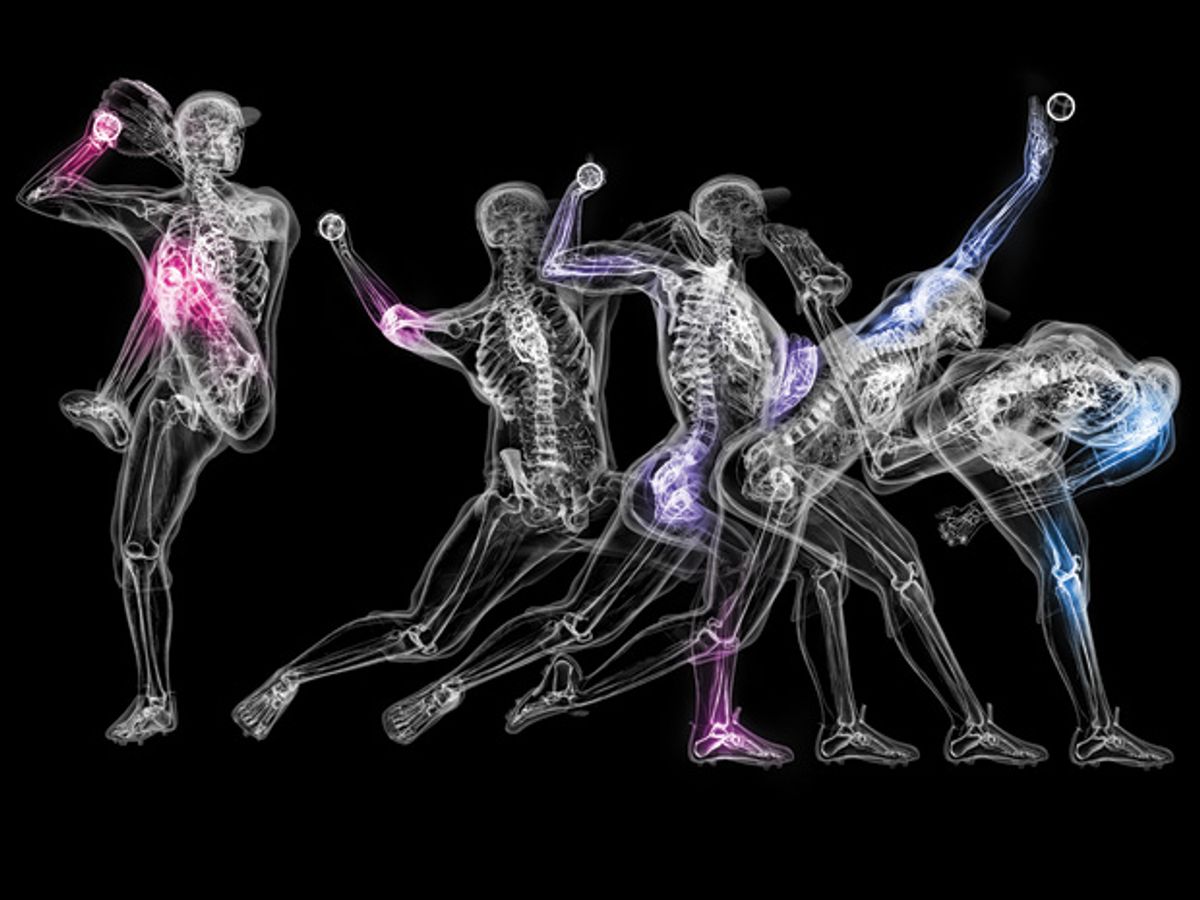

In his classicThe Sweet Spot in Time, John Jerome detailed the pursuit of the athletic sweet spot, of excellent execution over time. How do superb athletes, or teams of athletes, achieve peak performance over and over again? To the study of the biomechanics of movement and the biochemical breakdown of glucose, we now add the study of big data.

Major league baseball, to give one sports example, has relied on algorithmic data crunching to create models of the best possible combinations of players and field positions for more than a decade. Now baseball geeks can get jobs in team systems development, building the proprietary databases and machine learning software that supply the ingredients for the team’s secret playoff sauce.Professional sports was among the first “people” industries to embrace big data. In this issue, we describe how medicine is now mining big data to cure illness and possibly prevent it. And, eventually, we may try to make our exquisite biology even better than it is upon our arrival on terra firma. What hubris!

Before big data becomes big data—a mass of unruly bits that need to be tamed by combinatorial brute force—it is little data, our own personal data. New York Times reporter Steve Lohr calls the trend toward working with aggregated personal data “data-ism,” which he describes as “a point of view, or philosophy, about how decisions will be—and perhaps should be—made in the future.”

The ability to collect large amounts of little data via wearables (and soon ear-mounted hearables and even implanted disappearables) fuels health care’s “quantified self” movement, a term coined by Kevin Kelly and Gary Wolf in 2007. In 2013, a Pew Research Center study revealed that 69 percent of Americans were already tracking their diet, exercise, or a health indicator such as blood pressure, although only 21 percent were using technology to do so. Change is coming quickly: The consulting company IHS projects that more than 230 million wearable devices will be sold in 2019.

It’s useful to remember that we are, in our unadulterated biological forms, awash in self-monitoring systems, such as proprioceptors and mechanoreceptors that track body position and sensory receptors that tell us what’s going on in the world around us. In most cases we process this data effortlessly. Biometric devices make our internal monitoring systems transparent, so we can use the information that these systems are continually gathering to better effect.

Self-monitoring allows us to take an active role in maintaining and improving our health, to find our daily sweet spots. We don’t have to wait for doctors to see us: We can see what to do ourselves, in real time.

That’s the good news. But big data’s transformation of medicine also comes with big challenges. Data ownership and privacy will be prime among them. Where do all these data reside, how are they collected, curated, retrieved? Once they leave your device or your doctor’s office, where do they go and who gets to use them?

Even harder questions lie ahead. Clearly only a fraction of humanity will benefit from these early efforts. What happens to the rest? Will “all natural” human beings become the disabled among us? And how are we defining mental and physical excellence? Would Stephen Hawking have been a better physicist if his ALS had been repaired, or Beethoven a better musician with his hearing restored?

In baseball, when a pitcher is throwing well he’s said to be throwing seeds; the hitter can’t even see the ball coming. We’ll need to step up our game as the seeds of big-data changes in medicine start flying at us, fast and furious.

This article originally appeared in print as “Homing In On Health Care’s Sweet Spots.”

Special thanks to Eliza Strickland, the lead editor for this issue.