A “neural tourniquet” doesn’t sound like a thing thatshould work. Even its inventors admit it.

“It’s a real leap of faith: ‘I know, we’ll stimulate a nerve to control bleeding,’ ” says Chris Czura, a vice president of the Feinstein Institute for Medical Research, near New York City. “When you say this to surgeons, they look at you funny.”

But in the Feinstein team’s 15 years of research, it has gathered ample evidence for this type of bioelectronic medicine, with studies that show neural stimulation can prevent or stop severe hemorrhages in lab animals. Now the researchers are launching a clinical trial in humans to show the world that their strange idea doesn’t just work—it can save lives.

This tech is different from typical tourniquets, which have been used since Alexander the Great’s military campaigns in ancient Persia. When a soldier was wounded, one of Alexander’s physicians would tie a rope around the soldier’s limb above the wound, compressing the blood vessels and stopping the blood flow. In today’s emergency medicine, first responders use tourniquets in the same way.

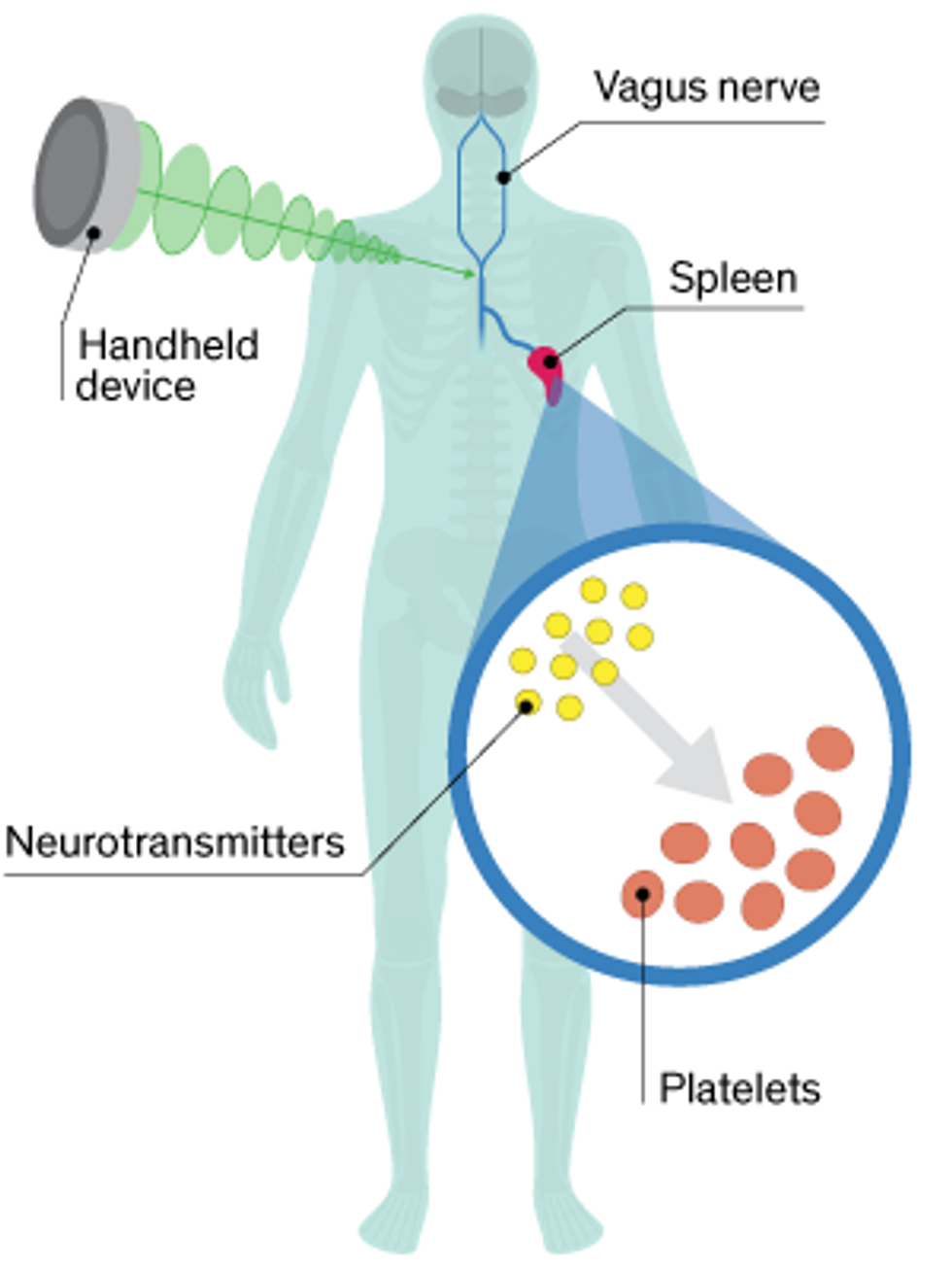

With the neural tourniquet, there’s no rope and no physical compression of the blood vessel. Instead, doctors press a handheld device against the skin (Czura won’t say exactly where, citing proprietary details) to stimulate the vagus nerve, which transmits information between the brain and the major organs. This nerve stimulation conveys a signal to the spleen, where platelets—cell-like structures in blood that form clots—receive their instructions. This signal causes nerve cells in the spleen to release a chemical that “primes” the platelets, prepping them to clot when they encounter a wound anywhere in the body.

“This grabs control of the mechanism the brain uses,” Czura says. “The body has this natural physiologic pathway to control bleeding, and this just ramps it up.”

A 2010 study in pigs found that the neural tourniquet reduced bleeding time by 40 percent and the volume of blood loss by 50 percent. And it worked quickly. Within 3 minutes of jolting the pig’s nerve, the researchers measured an increase in an enzyme associated with clotting at the site of injury, while enzyme levels remained steady elsewhere in the body. Other animal studies have demonstrated that the tech works for both internal and external injuries.

Czura and his colleagues say the neural tourniquet could be useful for battlefield medicine, emergency response, surgery, and postpartum care. It’s in that last category that the technology will get its first test. Sanguistat, a spin-off company from the Feinstein Institute, will test the tourniquet as a treatment for postpartum hemorrhage, the leading cause of maternal death worldwide. In Africa and Asia, excessive bleeding kills close to 80,000 new mothers each year. Sanguistat is partnering with the Bill Gates–backed Global Good fund to conduct clinical trials in both the United States and the developing world.

Experts on postpartum hemorrhage note that it’s a tricky condition to remedy, requiring the reestablishment of a delicate bodily balance. Andrew Weeks, a professor of international maternal health at the University of Liverpool, in England, explains that pregnant women already have an increased tendency to form clots. Doctors need to guard against thrombosis, he says, a potentially dangerous condition in which a clot forms and blocks a blood vessel.

Weeks also notes that researchers are making progress on pharmaceutical treatments for postpartum hemorrhage. He expects results soon from a worldwide study involving 20,000 women that’s testing an inexpensive drug called tranexamic acid. For the neural tourniquet to be widely adopted, he says, “it would need to be easy to obtain and use in an emergency, act rapidly—within a few minutes—and be reversible or transient to prevent thrombosis.”

Feinstein researcher and trauma surgeon Jared Huston hopes the neural tourniquet will become a new tool for surgeons. Before an operation, the stimulator could be applied as a protective measure against hemorrhage, he says, in the same way that patients get antibiotics before surgery to protect against infection. Huston would also like to have a better treatment for emergency-room patients, noting that he recently had a 30-year-old patient die from blood loss after a motorcycle accident. “If the surgeon doesn’t get in there to stop the bleeding in time, it’s game over,” he says.