The Baltic countries—Lithuania, Latvia, and Estonia—recently accelerated a plan to cut the electrical chains that keep them tied to Russia. A technical lynchpin to their planned escape from the Moscow-controlled synchronous AC power zone is a constellation of synchronous condensers: free-spinning and fuel-free electrical generators whose sole purpose is to stabilize and protect power grids.

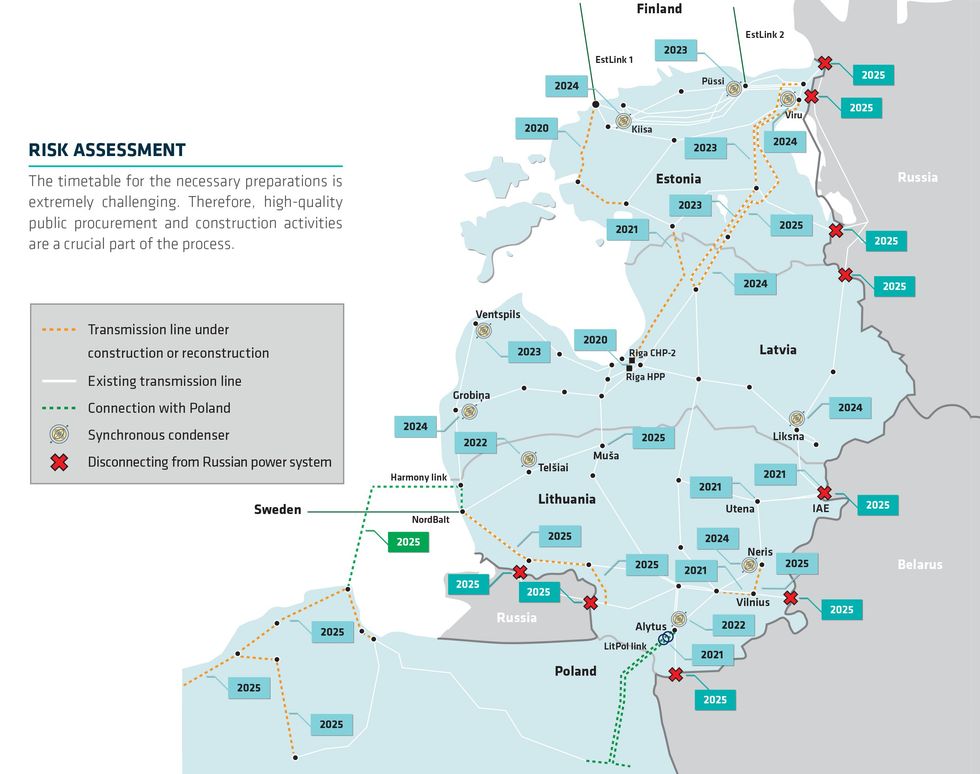

The Baltic states, all of which are members of the European Union and NATO, started freeing themselves from Russia’s electrical embrace almost a decade ago with the construction of high-voltage direct current (HVDC) connections to Finland, Sweden, and Poland. Those alternative sources of electrical support ended the Baltics’ dependance on imported power from Russia and Belarus.

Now stabilizing equipment is preparing the grid to be able to physically separate from the giant grid to the east, and to synchronize instead with the continental European grid to the south. In 2019, funding from the European Union jump-started the required grid-strengthening upgrades, and synchronization with Europe was scheduled for the end of 2025.

“Being on the Russian electricity grid is a risk for Estonian consumers.” —Kaja Kallas, prime minister of Estonia

Cost increases have delayed a crucial second link with Poland, and thus Europe, to 2028, but the full-scale invasion of Ukraine and Russia’s aerial assaults on the Ukrainian grid boosted pressure on the Baltics to break away faster. In August the Baltic states reached consensus on a plan to switch grids no later than February of 2025.

As Estonian prime minister Kaja Kallas explained: “Russia’s aggression in Ukraine and its use of energy as a weapon proves that it’s a dangerous and unpredictable country, and therefore being on the Russian electricity grid is a risk for Estonian consumers.” The prime ministers, she said, agreed to, “leave the Russian network as soon as the technical capacity is in place.”

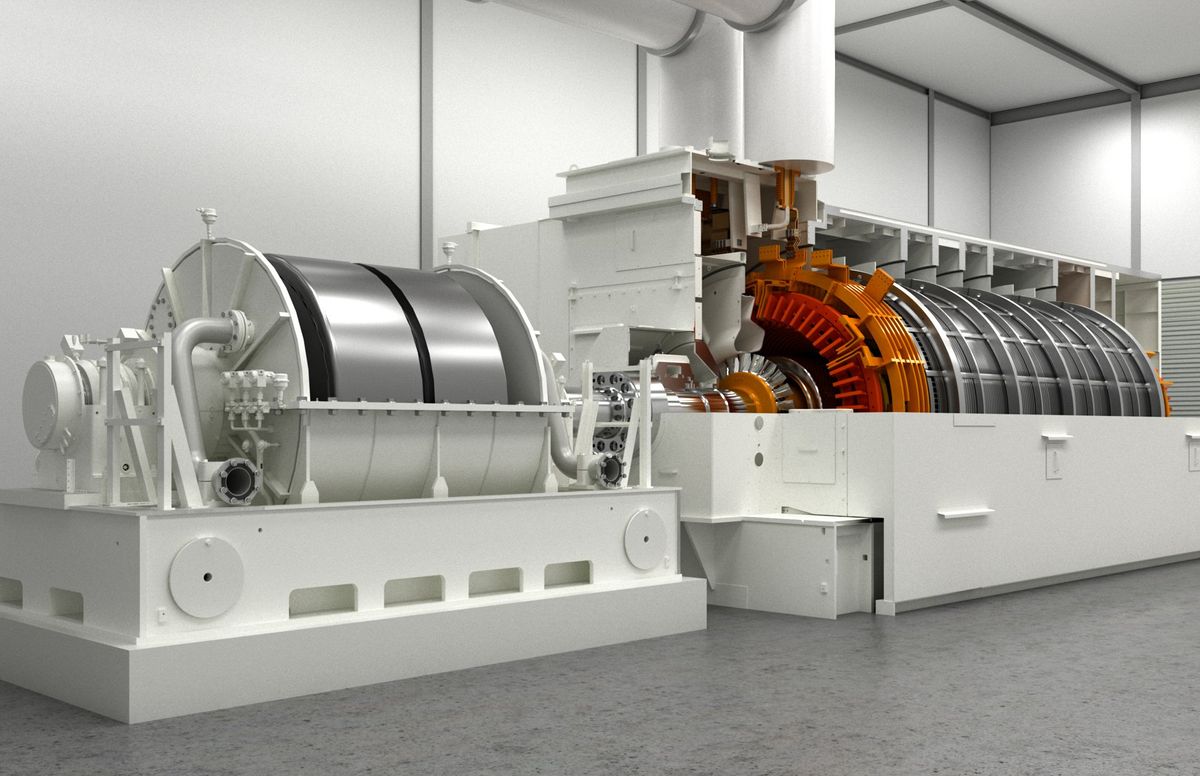

This is where synchronous condensers step in. Synchronous condensers (also called synchronous compensators) are essentially generators that, in normal operation, are spun by an AC grid’s power and synced to its frequency (rather than driven by their own fuel). When power plants or transmission lines shut down unexpectedly, the momentum in their spinning mass offers an instantaneous supply of energy that cushions the blow, thus protecting equipment and preventing outages.

“It’s like an airbag for the power grid,” says Ana Joswig, portfolio life-cycle manager for synchronous condensers for market leader Siemens Energy, supplier for the nine synchronous condensers scheduled to be operating in the Baltics by the end of next year.

Joswig says the spinning machines provide three crucial grid-stabilizing services:

- Frequency regulation: When grid power crashes or surges, the device immediately releases or absorbs energy to minimize fluctuation in the AC frequency;

- Short circuit power: When the grid experiences a short circuit, the crashing voltage releases a tripling or more of current from rotating machines, which signal breakers on the grid to activate and quickly isolate the fault; and

- Voltage support: Producing current and voltage that are out of phase generates so-called reactive power that pushes the local grid’s voltage up or down to stabilize system voltage, increase the flow of real power, or both.

Synchronous convertors were first deployed in the early 20th century, but they were rarely used because grid stabilization could be supplied by power plants with big spinning generators. But plants with steam and turbine-driven generators are increasingly being replaced by solar panels, wind turbines, and batteries that deliver their energy via electronic converters. Hence, a worldwide comeback for a technology that was invented over a century ago.

In recent decades AC grids are experiencing more events where synchronization breaks down.

Joswig says there’s been an extra growth spurt as the energy transition accelerated over the last several years: “Before, some grid operators told me there is no market for the synchronous condenser. Now they can not get enough.”

Synchronizing with Europe drives added need for grid services in the Baltics. Europe has very large power plants whose failure can cause larger disruptions than the Baltics have traditionally faced. And, notes Joswig, in recent decades AC grids are experiencing more events where synchronization breaks down, leaving some regions electrically isolated—a scenario that will be extra relevant for the Baltics while it is operating with just one AC link to continental Europe.

When IEEE Spectrum profiled the reemergence of synchronous condensers in 2015, there was a notable trend toward the conversion of steam generators as coal-fired and nuclear power plants shut down. Today’s notable tech trend, says Joswig, is the addition of flywheels weighing hundreds of tonnes to boost momentum. All nine of the Baltics’ synchronous condensers will have power-boosting flywheels, as she explains, equipping each installation with up to 2,200 megajoules of energy. That’s roughly equivalent to the kinetic energy of a 3,000-tonne train cruising at 100 kilometers per hour.

In addition to synchronous condensers and international links, the Baltics are further strengthening their electrical systems by upgrading control systems and adding and rebuilding transmission lines. Moving up the final line renovation, a circuit between Estonia and Latvia to be ready at the end of 2024, clinched the deal to accelerate synchronization with Europe.

Justinas Juozaitis, who heads the World Politics Research Group at Lithuania’s military academy, says Russian action forced the speedup. For one thing, he says, Russia prepared faster for Baltic separation.

Russia and Belarus built new lines to strengthen their own grids. And Russia built four gas-fired power plants and a liquefied-natural-gas import terminal in Kaliningrad, a Russian exclave on the Baltic Sea sandwiched between Poland and Lithuania. “By 2021 they had built the infrastructure and proved that Kaliningrad can operate independently,” says Juozaitis. That, he says, put Russia in a position to disrupt Baltic power without risk of blacking-out its own territory.

By the middle of 2022, the Baltics forged a protocol for “emergency synchronization,” by which it can switch to Europe’s grid in a matter of hours if necessary. The emergency plan calls for activation of transformers at the Polish-Lithuanian border, converting the country’s HVDC link to an AC interconnection, and provision of extra frequency regulation via plants in Sweden and Finland.

Juozaitis says the fact that European grid operators fast-tracked and completed Ukraine’s synchronization within one month of Russia’s invasion provides confidence that the Baltics can pull off an emergency switch. And he says recent events highlight the importance of being ready: mechanical damage sustained by a natural-gas pipeline from Finland to Estonia and by telecommunications cables linking Estonia to Sweden. They appear to have been struck around the same time in early October.

Finnish authorities investigating the pipeline damage say their prime suspect is a Chinese-flagged container ship, the Newnew Polar Bear; Estonian authorities have said they are tracking the Sevmorput, a nuclear-powered Russian cargo ship, that was also in the vicinity of the pipeline and cables when they sustained damage.

“The Russian federation has the motive, and the chronology is very, very strange,” notes Juozaitis. Russia and China have denied sabotaging the equipment.

Juozaitis says NATO has already stepped up naval patrols and other surveillance in the Baltic to protect infrastructure. But he says the Baltics also need to practice deterrence. As he puts it: “They must be signaling that if the Russians continue tampering with submerged infrastructure there are going to be consequences.”

- Zombie Coal Plants Reanimated to Stabilize the Grid ›

- Fear of Russia Drives High-Voltage Power Projects in the Baltics ›

- How Russia Sent Ukraine Racing Into the “Energy Eurozone” ›

- This Clock Made Power Grids Possible - IEEE Spectrum ›

- Grid-scale Batteries in Scotland Stabilize Power - IEEE Spectrum ›

Peter Fairley has been tracking energy technologies and their environmental implications globally for over two decades, charting engineering and policy innovations that could slash dependence on fossil fuels and the political forces fighting them. He has been a contributing editor with IEEE Spectrum since 2003.