In a move inspired by natural engineering, robotics researchers have demonstrated how tiny palm-size drones can forcefully tug objects 40 times their own mass by anchoring themselves to the ground or to walls. It’s a glimpse into how small drones could more actively manipulate their environment in a way similar to that of humans or larger robots.

“Teams of these drones could work cooperatively to perform more complex manipulation tasks,” says Matt Estrada, a Ph.D. student in mechanical engineering at Stanford University. “We demonstrated opening a door, but this approach could be extended to turning a ball valve, moving a piece of debris, or retrieving an object of interest from a disaster zone.”

Winged creatures such as birds, bats, and insects can lift only objects that are about five times their own weight when flying. But Estrada and his colleagues from Stanford University and the École Polytechnique Fédérale de Lausanne, in Switzerland, looked instead to the practical approach taken by predatory wasps, which land on the ground to drag larger prey back to their nests. The group’s bioinspired approach to robotic experimentation is detailed in the latest issue of Science Robotics.

The “FlyCroTug” drones also represent an evolution for ground-based robots originally developed by David Christensen, a coauthor on the paper who is currently employed at Disney Research. By turning to a custom-built quadrotor drone design, the team created micro air vehicles that combine aerial mobility with greater pulling or pushing strength based on ground anchoring.

Each FlyCroTug drone has a specialized attachment at the end of a long cable that can be paid out and then pulled back in through a winch. That means the drones can attach one end of their cable to an object, fly off, land, and anchor themselves before hauling the heavy load toward them. What might normally be one small step at a time for wasps becomes one giant flying leap at a time for the drones, Estrada explained.

The anchoring mechanisms based on technologies from Stanford’s Biomimetics and Dexterous Manipulation Lab also took inspiration from natural design: microspines capable of attaching to rough stucco or concrete surfaces, and sticky, gecko-inspired adhesives for attaching to smooth glass.

Having tiny drones that can explore cramped spaces and still exert large forces upon their surroundings opens many new possibilities for search-and-rescue applications in either civilian or military scenarios. For example, Estrada suggested that such drones could be a portable tool for first responders or military personnel to deploy sensors or transport medical supplies to a person stuck in a remote location.

In one of the team’s experiments, a FlyCroTug drone clung to an overhang as it pulled up a battery-powered camera to perform inspections of a collapsed building site at a military training facility outside of Geneva, Switzerland.

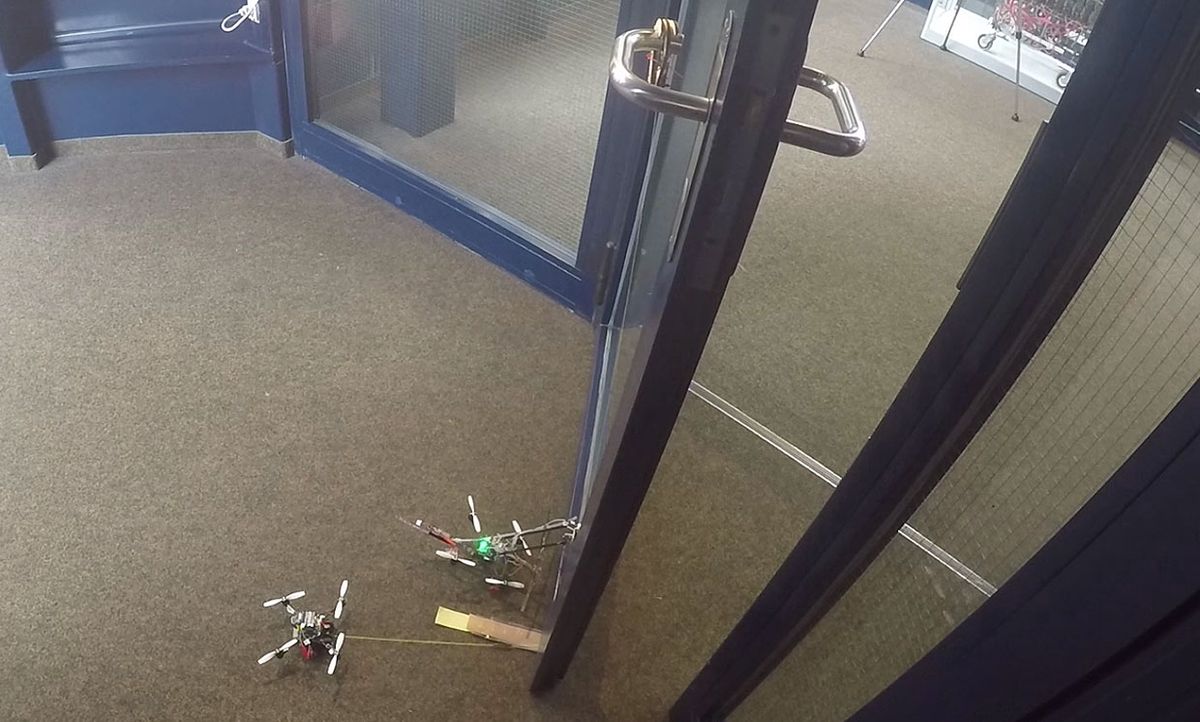

A second door-opening scenario required teamwork between two FlyCroTug drones. The first drone grabbed the door handle with a special grappling attachment and then anchored itself to the smooth glass door. The second drone slipped a hook under the door and then latched onto the nearby carpet to pull the door open, once the handle had been turned.

As impressive as this all sounds, the FlyCroTug drones still face serious limitations. Their current battery life is sufficient for just five minutes of flight time, which severely limits what they can do. Complex and unknown environments would also require possibly many versions of the drones with different attachments and anchor mechanisms for various surfaces. But the latter may not be a problem, if such flying robots could be made cheaply and be deployed as swarms of disposable drones.

Researchers have not yet developed either sensing capabilities or artificial intelligence capabilities for such drones to operate even semi-independently, let alone in fully autonomous mode without human control. But Estrada believes that a teleoperation approach makes the most sense for near-future deployments of such technology.

“Humans can intuitively read a room and predict what surfaces might be suitable to attach onto and [find] feasible paths towards these locations,” Estrada says. “This could certainly be combined with some low-level autonomy for maneuvers such as holding a position or grappling a handle.”

Jeremy Hsu has been working as a science and technology journalist in New York City since 2008. He has written on subjects as diverse as supercomputing and wearable electronics for IEEE Spectrum. When he’s not trying to wrap his head around the latest quantum computing news for Spectrum, he also contributes to a variety of publications such as Scientific American, Discover, Popular Science, and others. He is a graduate of New York University’s Science, Health & Environmental Reporting Program.