This is a guest post. The views expressed here are solely those of the author and do not represent positions of IEEE Spectrum or the IEEE. This post was originally published at the Flexport Blog.

Two years ago, Jeff Bezos promised that Amazon would soon deliver packages by drone. “I know this looks like science fiction," the Amazon CEO told Charlie Rose on “60 Minutes" as he stood with several Amazon drones. “It's not."

Bezos's primetime announcement sparked a lot of interest—and a media consensus that it was a publicity stunt to get Christmas shoppers thinking about Amazon. After all, federal law prohibited commercial drones from flying over populated areas, and airplanes were already experiencing close calls with hobbyists' drones.

But the drone community is not acting like the prospect of delivering packages by drone is a pipe dream. Amazon just released an update of its Prime Air program. Executives at Google Wing claim they will deliver packages in 2017 via drone. Walmart has asked the Federal Aviation Administration for permission to test drone delivery, and venture capitalists have invested in drone delivery startups.

So what makes the drone community believe deliveries are a good idea? Assuming the technology works, do the economics make sense?

The Drone's Milk Run

Drone deliveries look like the future: unmanned quadcopters rapidly delivering packages to our doors, eliminating both wait times and the cost of human labor.

But from an economic perspective, it's easy to see how drone delivery could be an elegant technological solution in search of a problem.

That's because the economics of last-mile delivery are driven by two factors: route density and drop size. Route density is the number of drop-offs you can make on a delivery route, often called a “milk-run" in industry parlance. Drop-size is the number of parcels per stop on the milk run.

If you make lots of deliveries over a short period of time or distance, the cost per delivery will be low. Likewise, if you drop off lots of parcels at the same location, the cost per parcel will be low.

Drones perform poorly on both of these economic aspects of last-mile delivery. The current prototypes that companies have unveiled usually carry just one package, and after the drone makes its delivery, it has to fly all the way back to its homebase to recharge its batteries and pick up the next package.

Compare that to the current status quo: delivery trucks. A delivery truck from UPS makes an average of 120 stops a day to deliver hundreds or thousands of packages. Don't they seem to be better than drones?

How Short-Distance Drone Deliveries Work

Last November, Amazon released a slick video demo of Prime Air, a drone delivery system designed to “get packages to customers in 30 minutes or less." It comes on the heels of a similar production from Google's Project Wing, which showed a drone delivering dog food in Queensland, Australia.

Both these companies and others say they expect to be flying soon.

We approached these companies' claims with skepticism. After all, in Amazon's demo, a drone that the company says can fly 15 miles delivers a pair of soccer shoes. But what if you don't live within 7.5 miles of an Amazon warehouse? And will Amazon keep drones on standby for when you order 50 pounds of diapers? Drone delivery is still speculative, and Amazon and co. aren't revealing all their plans. But a few simple statistics show that distance and weight may not hold back drone delivery.

In official documents, Amazon has written that 86 percent of its packages weigh under 5 pounds. As for distance, Walmart has noted that 70 percent of Americans live within 5 miles of a Walmart. This is great for the prospect of drone delivery. Amazon's fulfillment centers are not as ubiquitous, but the company has shown willingness aplenty to move its products and warehouses closer to the customer.

If products start close enough to consumers that drones can deliver them in 30 minutes, we may very well see drone delivery even if it costs more than the humble UPS truck. “Faster delivery has always been a goal," says Logan Campbell, the CEO of Aerotas, a drone consultancy. “Seven-day delivery was common. Now we've become used to Amazon Prime 2-day delivery."

There haven't been many analyses of drone air freight costs. The ones that do exist suggestion that drones have the potential of being both faster and cheaper than delivery costs.

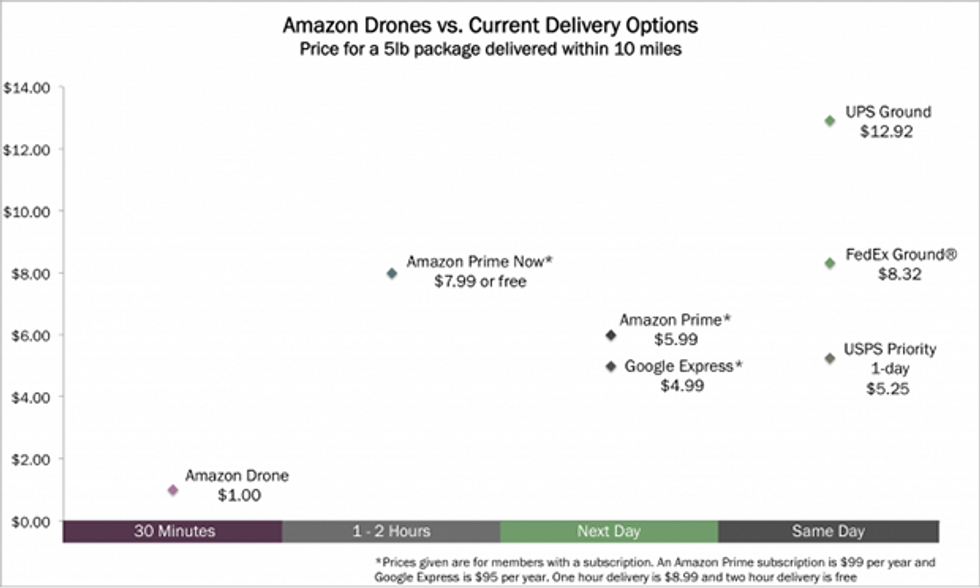

In a report by ARK Invest, Tasha Keeney suggests that Prime Air could cost Amazon only 88 cents per delivery. If Amazon charged customers $1 per delivery, Keeney estimates, the company could earn a 50% return on its investment in drone infrastructure while offering same-day delivery that is significantly cheaper than current alternatives.

The analysis is still mostly speculative. Keeney imagines that 6,000 operators who earn $50,000 per year will operate 30,000 to 40,000 drones. Each drone will make 30 deliveries per day. Her analysis ignores depreciation, and questions like: “How will drones avoid airplanes and deliver packages in Manhattan?" And there's another core issue: $12.92 is the price UPS charges to consumers, but its actual marginal cost of delivering one more package along a route they are delivering to already is probably closer to $2. When push comes to shove, will drones be able to compete? The rest of her analysis incorporates the costs of electricity, backup battery packs, bandwidth, upgrades to facilities, and so on.

Keeney's assumptions also stick to the middle ground: She presumes that Amazon will gain permission to fly drones out of sight, with each operator responsible for 10-12 drones, but not that Amazon will soon automate the entire process. That said, other analyses, which assume that more pilots will be needed, put the cost closer to $10-$17 per delivery.

Delivering Blood Samples in Lesotho

An experiment from the other side of the world offers some validation of ARK's rosy prognosis.

The drone startup Matternet is not just planning a drone delivery network. It has already run one—in Lesotho, a landlocked country surrounded by South Africa.

Matternet has delivered crucial supplies (and chocolate) via drone in Haiti after the earthquake, and when the founders wanted to prototype a drone network, they turned to Maseru, the capital of Lesotho. In Lesotho, almost one in four adults has HIV, and even in the capital, paved roads are scarce, which makes it difficult to transport goods. So Matternet's drones delivered blood samples from clinics to hospitals where they could be analyzed for HIV/AIDS.

Blood samples were perfect cargo: small, light, valuable, and time-sensitive. Since Maseru has little air traffic and the routes from the clinics to the hospitals did not change, most of the process could be automated. The drones flew without a human pilot and had clear landing areas where they recharged automatically. Matternet CEO Andreas Raptopoulos says it took their drones 15 minutes to fly 4.4 pounds of cargo 6.2 miles, and that the Maseru network successfully covered an area 1.5 times the size of Manhattan.

It was a good price point. Even though the pilot took place several years ago, Raptopoulos says that each delivery cost only 24 cents.

Test Cases for Drone Deliveries

The first legal delivery in the United States via drone took place on July 17, 2015.

That day, a drone operated remotely made three trips to transport medicine from the Lonesome Pine Airport in Wise, Virginia, to a nearby fairgrounds. The demonstration was the result of a partnership between the drone startup Flirtey and two organizations that provide healthcare in rural, underserved areas.

The flight demonstrates two aspects of the future of drones and air freight: that technology is not the limiting factor, and that drones' most obvious appeal is not for personal deliveries.

“The technology is here," says Logan Campbell of Aerotas. “You see fully autonomous flights already" for uses like surveying construction sites, farmland, and mining operations.

“It's gotten incredibly easy to fly," adds Roger Sollenberger, spokesman of 3D Robotics, whose free, open source software powered Flirtey's delivery drone. 3D Robotics' drones, he says, make it so easy to program flight paths that the average parent can use it to record family moments.

Instead, the real challenge is the regulatory environment. The FAA has banned all commercial uses of drones in the U.S., and while the agency increasingly grants exemptions, the Flirtey flight is the only freight exemption that allowed a real delivery rather than testing in unpopulated areas.

The experts we spoke to expressed cautious optimism that the FAA, which is working on guidelines for drone deliveries, will let them fly. The FAA currently requires companies with exemptions, like Amazon, to have an operator with a pilot's license keep each drone within line of sight—a mandate that makes deliveries completely uneconomical.

Can Drones Substitute Roads?

In the meantime, the first drone deliveries will probably look more like Matternet's drone network in Lesotho and Flirtey's medicine drop in Wise, Virginia. It's much easier to operate and gain legal permission to fly in open skies, and the economics are particularly compelling.

As Raptopoulos of Matternet points out, Google and Amazon's plans ignore drones' best feature: they can go where there are no roads.

“One billion people in the world today do not have access to all-season roads," Raptopoulos told a TED audience in 2013. “We cannot get medicine to them reliably, they cannot get critical supplies, and they cannot get their goods to market in order to create a sustainable income."

For the Matternet team, the most interesting question was not the cost per delivery. They wanted to compare the cost of the drone network to the cost of building the roads Lesotho so badly lacks.

The American Road and Transportation Builders Association estimates the cost of a “new 2-lane undivided road" at $2 million to $5 million per mile. And the drone network in Maseru? “Less than a million dollars," Raptopoulos said in 2013.

Comparing a drone network to roads that can transport buses, delivery trucks, and bulldozers is not an apples to apples comparison. But given that building and maintaining roads is a long and expensive process, drones could offer a quick and cheap way to (imperfectly) connect the billion people identified by Raptopoulos as cut off from most of the world.

“Many in the industry think delivery will take a different feel from Amazon," says Campbell of Aerotas. “More specialized cases like delivering vaccines that need to be refrigerated to regional hospitals . . . Niche deliveries where speed is critical."

In these cases, for cargo that is small, light, valuable, and time-sensitive, cost is much less of a factor. A drone delivery may save a life by getting delicate medicine to a rural patient, or keep an oil rig running by delivering a key piece of machinery.

Even in less extreme cases, drones are appealing because route density and drop size are less relevant. Instead, drones just need to beat the cost of private couriers, which cost at least $10 to $50, even within dense urban areas like San Francisco.

Hospitals that need delicate medicines. Oil rigs that need replacement parts. Residents in remote Alaskan towns that need key supplies. Companies that need timely data about their supply chains. Expect these (noncommercial) efforts to be the early adopters of drones and drone delivery.

When Is The Future?

Drones are in a situation similar to the one faced by self-driving cars. Companies have demoed the technology, so the real obstacle is the legal and regulatory environment. In both cases, this means integrating the technologies into daily life could take a long time—or it could happen very quickly.

Current drone economics are good for deliveries that take less than 1 hour. Are people willing to pay a major premium for the service? Perhaps. It may not be too late to order Christmas presents on December 23, 2020!

Despite the current inability of drones to match the efficiency of a delivery truck's milk run, the economics of delivering air freight by drone seem compelling. That's why Amazon and Google are investing in the R&D. That's why Matternet is testing drone deliveries with Swiss Post and Swiss World Cargo. And that's why the drone community expects deliveries to happen—even if not as quickly as executives like Bezos promise.

In the meantime, drone deliveries will probably get their start in remote areas like Lesotho, or in use-cases like flying vital machine parts to oil rigs and mines, or by collecting data on shipping to make it more efficient.

Dan Wang writes about logistics and global trade for the Flexport Blog. Flexport is a freight forwarder providing services and software to coordinate global trade.