You walk into the brightly lit space, and a delicate-looking plaster statue catches your eye. She has a peaceful expression, and is dressed in a modest gown with puffy shoulders and a broad skirt. Her arms stay close to her body, but the palms of her hands face gently forward, as if asking for something. As you approach, she suddenly glides forward to meet you. Her name is Diamandini, and she's a robotic statue.

Combining art and robotics is nothing new (in fact, it's something quite old), but in recent years the creations dreamed up by artists and roboticists are becoming more elaborate and striking, thanks, in part, to faster and cheaper sensors and computers. We've seen robotic sculptures that defy gravity, robots that can paint and write, and squads of drones that play music, build towers, or perform choreographies. A number of workshops and festivals have gathered researchers and others interested in exploring the intersections of art and robots.

Over the last 15 years, art and technology have come together at the studio of Dr. Mari Velonaki. She is an artist and director of the Creative Robotics Lab at the University of New South Wales, in Australia. Velonaki and her team created the Diamandini installation at the Victoria and Albert Museum in London last fall.

Velonaki's Diamandini was part of a five-year project that ends this year. The goal was not just building interesting robotic machines, but also gathering data on how visitors interacted with the installations. Velonaki and her team recorded data of how more than 28,000 people interacted with their robotic statue. Their work gives us a glimpse into how robots can make an emotional connection to engage humans.

In 2009, Velonaki set out to "make something you wanted to hug, [just as parents] want to embrace their children." The result was Diamandini, designed to elicit a social and physical response from visitors. Velonaki says that, on average, about 80 percent of visitors reached out to touch the robot's hands, arms, or torso. She says that their current research involves adding a flexible, soft touch sensor that will let them record a broader range of physical interactions, from a subtle stroke to a hard push or poke.

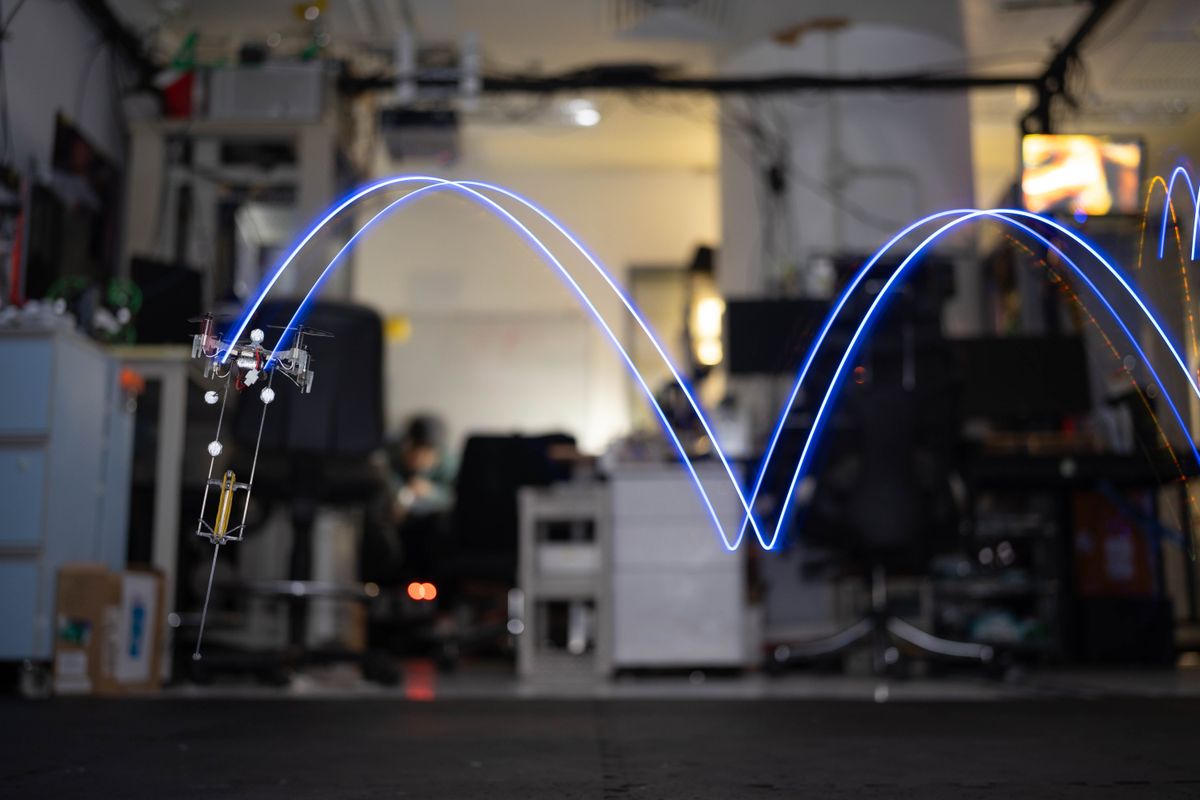

To enhance the illusion that the robot had a will of its own, the team, which includes Dr. David Rye from University of Sydney’s Centre for Social Robotics, used off-board cameras and lasers to let the robot navigate autonomously in the exhibition room. This approach is similar to their previous long-term robotics installation, Fish-Bird.

Velonaki’s Fish-Bird project from 2006 involved two robots named Fish and Bird. Visitors were told that the two robots couldn't be together due to "technical difficulties." The robots were shaped as empty wheelchairs, which Velonaki designed to evoke a feeling of absence of a person. The robots left love letters to each other via a miniature thermal printer, with poetic lines and personal confessions such as "my heart is broken" or "I'm so lonely," to produce empathy in the visitors. Each robot portrayed its personality through different cursive scripts printed on the papers and "outgoing" or "reserved" movements. For example, they faced visitors as they entered, and rolled alongside them, acknowledging their presence. Visitors that spent more time with the robots received more intimate messages from them. The two robotic chairs have interacted with over 36,000 people in Australia, Austria, Denmark, United States, and China.

So what has Velonaki learned with her robotic creations? The first thing is that, clearly, people loved them, or at least seemed attracted to them. She says that, on average, visitors to Fish-Bird interacted with the robots for about 10 minutes. Some of them became so deeply absorbed that they spent 30 minutes or more in the installation space. "Kids were patting them to print messages," says Velonaki. The engagement is remarkable in the context of an art exhibition, where visitors typically only spend a few minutes before moving on.

Another observation, Velonaki adds, is that "participants were attracted to the robots not because of the way they look but because of the way they behave." And yet, she says, noting her many years of robot interaction experience, creating a successful project takes time and lots of trial and error. "Only one thing is sure: humans are unpredictable."

Velonaki and Rye, along with their colleague David Silvera-Tawil, from the University of New South Wales, discuss the Diamandini and Fish-Bird robotics installations in the paper "Affective Human-Robot Interactions in Social Spaces: Two Case Studies," presented at the IEEE International Conference on Human-Robot Interaction in March.

Images and videos: Mari Velonaki