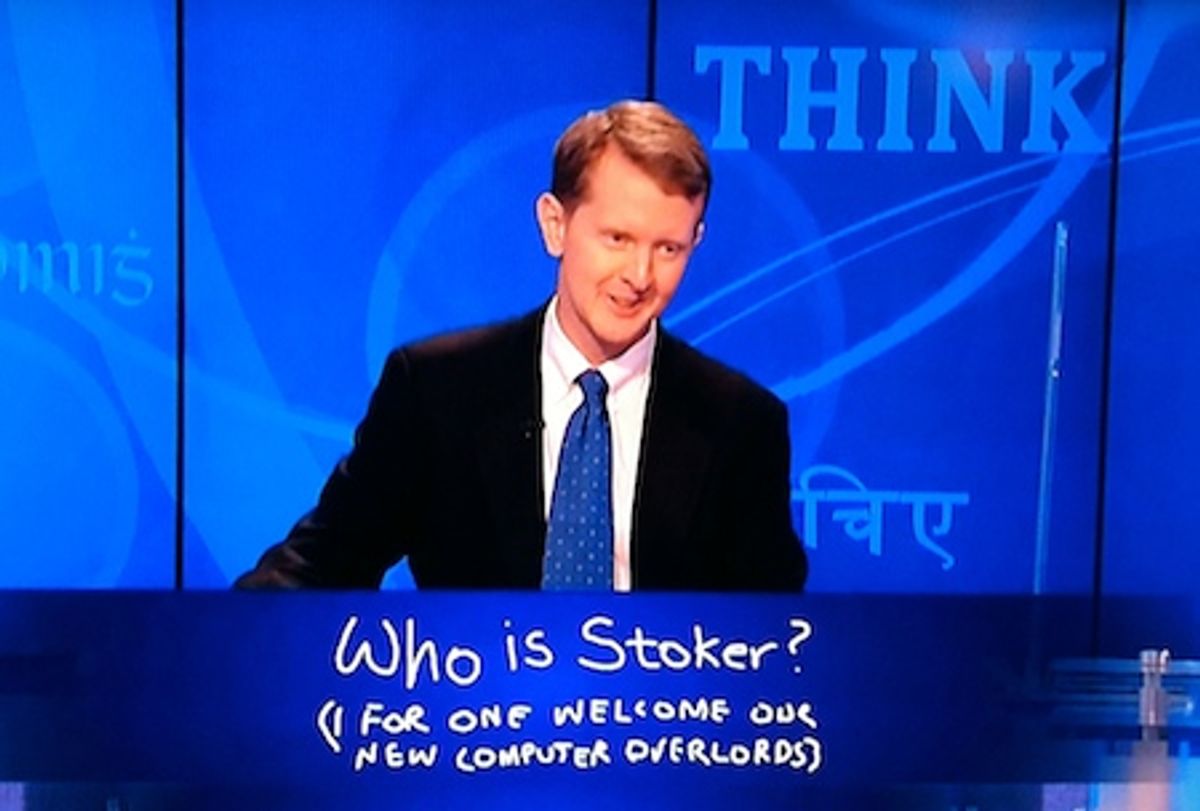

Watson, the Jeopardy supercomputer created by IBM, defeated its human opponents, Ken Jennings [above] and Brad Rutter, in the final round of the challenge.

The Jeopardy-IBM challenge has ended, and silicon prevailed over gray matter. Watson, the Jeopardy-playing supercomputer designed by IBM, defeated its human competitors, finishing in first by a wide margin.

As one of the contestants, Jeopardy super champion Ken Jennings, put it, “I for one welcome our new computer overlords.”

In this third and final round, Watson’s performance was much more impressive than its lackluster debut, but not as enthralling as in Day 2, when it completely dominated the game, except for its now-infamous “What is Toronto?????” mistake. This was one of a few errors that proved embarrassing for IBM, but perhaps entertaining for viewers. Watch what happened:

The final game started with Jennings, Watson, and the third contestant, Brad Rutter, another Jeopardy champion, each getting a bunch of answers right. It was funny to see that one of the categories was “Also On Your Computer Keys.” You’d expect that Watson, a computer, would know about computer keys. Not! When this clue, “It’s an abbreviation for Grand Prix auto racing” came up, Watson’s choices (shown to viewers on the TV screen) were “gpc,” “NASCAR,” and “QED.” Apparently Watson doesn’t know about the “F1” key.

The Final Jeopardy category was “19th Century Novelists,” and the clue, “William Wilkinson’s ‘an account of the principalities of Wallachia and Moldavia’ inspired this authors’s most famous novel.” The score at this point: Watson with $23,440, Ken with $18,200, and Brad with $5,600.

Both humans got it right, answering: “Who is Bram Stoker?” Brad’s total score from this round plus the previous rounds was $21,600. Ken finished just a little ahead with $24,000. What about Watson? No flubs this time. The computer got the answer right and finished with a commanding total of $77,147.

It might be worth to note that if Ken had wagered all he had, he’d have ended up with a final total of $41,200, and if Watson had wagered all it had but got it wrong, its final total would’ve been $35,734—in this scenario, Ken would have won! So why didn’t Ken take the chance? Did he think the odds of Watson making such a big mistake were too slim? Indeed, Watson was very confident in its answer: It wagered the exact amount ($17,973) that, even if it had gotten the answer wrong, would keep its score ahead of Ken’s; in this case, Watson would end up with $41,201 and Ken with $41,200. A $1 dollar difference! Now that would’ve been great television.

By winning the challenge, Watson not only helps IBM advance its master plan of making humanity obsolete but it also earns the company the $1 million top prize. The money, though, will go to charity. Sorry, Watson, no CPU upgrade for you!

So what does Watson’s victory mean for the future of AI? Will it help advance the field or is it just a publicity stunt that will benefit IBM’s image but have limited practical applications, much like the Deep Blue vs. Kasparov matches?

IBM insists that Watson “changes the paradigm in which we work with computers” and will “transform many industries.” As examples, they say Watson could help clinicians trying to diagnose a hard case, or lawyers sifting through mountains of evidence material, or governments and companies managing natural resources like water.

From a more fundamental point of view, Watson is part of a shift in AI that has put emphasis on systems that are not programmed to solve problems but rather programmed to learn how to solve problems. Peter Norvig, Google’s director of research, recently wrote about the promises of this new direction in AI:

This approach of relying on examples — on massive amounts of data — rather than on cleverly composed rules, is a pervasive theme in modern A.I. work. It has been applied to closely related problems like speech recognition and to very different problems like robot navigation. IBM’s Watson system also relies on massive amounts of data, spread over hundreds of computers, as well as a sophisticated mechanism for combining evidence from multiple sources.

The current decade is a very exciting time for A.I. development because the economics of computer hardware has just recently made it possible to address many problems that would have been prohibitively expensive in the past. In addition, the development of wireless and cellular data networks means that these exciting new applications are no longer locked up in research labs, they are more likely to be available to everyone as services on the web.

So maybe in a few years we’ll all be carrying a Watson app on our smartphones. It will destroy us on a “Jeopardy!” game, but help us mine data, connect dots, and solve some of our hardest problems. Do you agree? What do you think Watson means for the future of computers—and humanity?

Updated February 22, 2011

Erico Guizzo is the director of digital innovation at IEEE Spectrum, and cofounder of the IEEE Robots Guide, an award-winning interactive site about robotics. He oversees the operation, integration, and new feature development for all digital properties and platforms, including the Spectrum website, newsletters, CMS, editorial workflow systems, and analytics and AI tools. An IEEE Member, he is an electrical engineer by training and has a master’s degree in science writing from MIT.