Management American Style

A U.S. university teaches Western business ways to Chinese students

Song Xiaoxuan was baffled when, during a lecture one morning, the visiting American professor locked out one of Song’s classmates, who had left to use the restroom. Then he realized it was all in jest. “Everyone laughed and was shocked that a professor would joke like that,” Song recalls. “In China, the professors are very earnest and serious.”

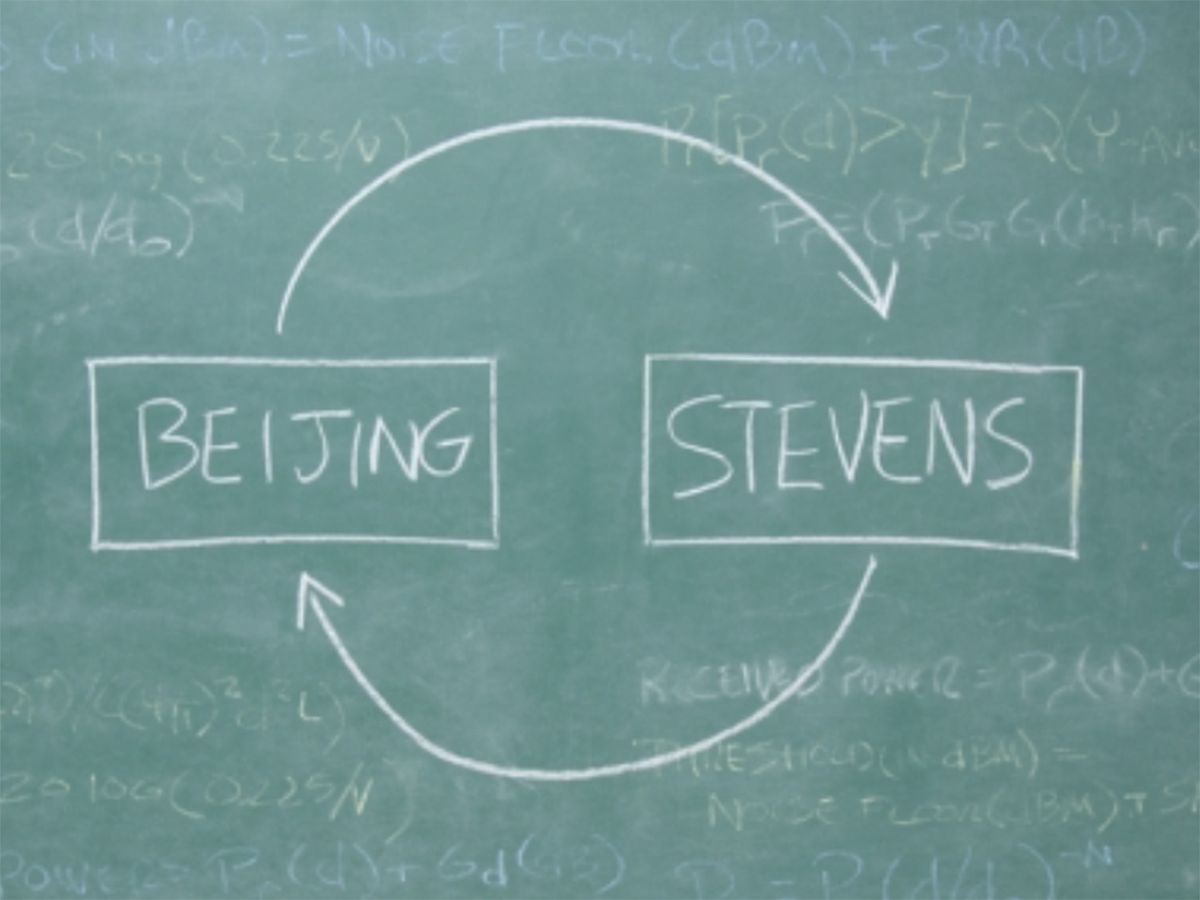

The cross-cultural camaraderie played out in a classroom in Beijing. Song, a 25-year-old electrical engineer from Heilongjiang province, and 20 other students were working toward their master’s degrees in telecommunications management from Stevens Institute of Technology, a small engineering school based half a world away. The curriculum is similar to one Stevens offers on its main campus in Hoboken, N.J., but the classes were held at the Beijing Institute of Technology (BIT). Two-thirds of the teaching was on campus, and for the rest, the students logged onto Web-based tutorials.

For the 18-month program, the students paid about US $12 000 in tuition—five times the cost of a two-year master’s program in China. But in a country that is booming and yet struggling with a glut of technically trained workers, a U.S. university degree is seen as a way to stand out.

The Stevens program is part of a wave of international higher education coming to China. While China has sent hundreds of thousands of students to study abroad, it has recently been aggressively expanding its own academic system. Since 1999, undergraduate enrollments have quadrupled, to 4.2 million.

Such rapid expansion brought concerns about the quality of education—there are only so many professors to go around, after all—so the government began inviting foreign schools to set up educational programs in China. There are now 800 such cooperative efforts, the majority run by U.S. schools. “We were eager to cooperate with Stevens, because China has been a closed society for so long,” notes Xue Wei, the associate dean of BIT’s school of information engineering. “We want to learn from American schools, to have a window to see how they train graduate students.” Yang Jun, an official in China’s Ministry of Education, in Beijing, put it more bluntly: “The United States has the best-quality higher education resources in the world.”

What schools like Stevens are getting in return is the opportunity to tap into a fast-growing, technology-hungry market. Although Stevens has been around for 125 years, the Beijing program was its first foray abroad. It plans to launch similar programs in September at Shanghai Jiao Tong University and the Central University of Finance and Economics, Beijing. Audrey Curtis, project director of Stevens’s graduate program in telecommunications management, says, “We wanted to go where the business is. And that’s China.”

One factor driving more Chinese students to get a U.S.-style education at home is that since 9/11 they’ve had a much harder time getting into the United States. In 2001 the U.S. State Department issued more than 32 000 student visas to Chinese citizens, whereas last year, it issued about 25 000. Xu Zhaomeng says she enrolled in the Stevens Beijing program after her visa application to attend grad school in the United States was denied three times. “I didn’t think I had any hope after that,” she says.

Some 220 000 students earned engineering bachelor’s degrees in China last year, and another 100 000 earned engineering master’s degrees and Ph.D.s, which means that China now graduates more engineers than the United States, Japan, and Germany combined. The result is that, despite runaway growth in every high-tech sector, the Chinese job market is swamped with engineers.

Two months after graduating, only a quarter of the Stevens students had found jobs, and half continued to look for work. The others planned to pursue further degrees. The problem may be that Stevens doesn’t have the name recognition of, say, the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, and the field of technology management is still new. Many employers “don’t understand the worth of this program,” says student Chen Yan, who got a job at 263.net, an Internet service provider in Beijing. Stevens’s Curtis agrees: “It is still to be seen how industry accepts these programs.”

By most accounts, the educational experience itself was rewarding and often surprising. Being called on in class, giving presentations to classmates, and working in teams were all new experiences for the students. As student Zhang Geng put it, “Chinese education is usually very theoretical. But here, every class is suited toward applying the information to a job.”

The Chinese professors also found the experience novel. “It was strange to have to give quizzes regularly, and to have to go over the answers,” BIT professor Liu Jiakang says. Tests in China are used strictly to evaluate, not as a learning tool.

In January, the first class of Stevens Beijing students gathered in a small auditorium at BIT to receive their diplomas. The printed program helpfully spelled out the quirks of the Western-style graduation ceremony, complete with gowns, mortarboards, and a recording of the Stevens alma mater warbling in the background. The blizzard of photo taking afterward by proud parents of relieved students and their beaming professors needed no translation.

About the Author

Jen lin-liu is a freelance journalist based in Beijing.