An engineer spend ing time at work reading fiction stories about the future—or worse, watching sci-fi movies—could upset, even anger, his or her manager. But what if there’s a possibility that by engaging speculations about the future, engineers can enrich their capacities for creating designs and artifacts, in the here and now, of enduring value?

A small but growing cadre of savvy technologists argue that, at least in measured doses, encounters with imaginary worlds and futuristic devices could have a decisive influence on innovation. David Brian Johnson, Intel’s staff futurist, even insists in a recent book, Science Fiction Prototyping, that by writing stories about future products, engineers can do a better job of actually making them.

Hold on. Isn’t fiction escapist, a waste of an engineer’s time?

It depends. Wernher von Braun, the pioneer of rocketry, was inspired by Jules Verne’s stories of travel to the moon. Leo Szilard, who worked on the first atomic weapons, was inspired by H.G. Wells’s The World Set Free (1914).

To be sure, the design for Apple’s iPhone11 isn’t likely to come from the pen of a storyteller. Yet recall that, in 1988, Apple made a promotional video that introduced an imagined tablet computer called the Knowledge Navigator, which even possessed a talking virtual assistant uncannily similar to the iPhone’s Siri. Twenty‑two years later—when the key components became small, cheap, fast, and smart enough—the fictional Knowledge Navigator morphed into the iPad.

The value of imagining future systems is partly promotional. Steve Jobs constantly spoke of building products people want but don’t know they want. Sony’s legendary founder Akio Morita often described the task of engineering in the same way.

Scholars of innovation, such as Clark Miller, an electrical engineer who coteaches a class with me on writing about the future, are keen to encourage engineers to embrace speculative fiction for noncommercial reasons. They say human values are sometimes not reflected in new gadgets and systems and that engineers can better account for the “human dimension” in their work if they imagine what the world would be like—and what adaptations people would have to make—if their inventions came into widespread use.

So how might engineers begin to bridge, through fictions about the future, the divide between human aspiration and the machines and systems they conceive, design, and create?

The short answer is for engineers to write stories or create videos of their own. Here are three easy steps to getting started:

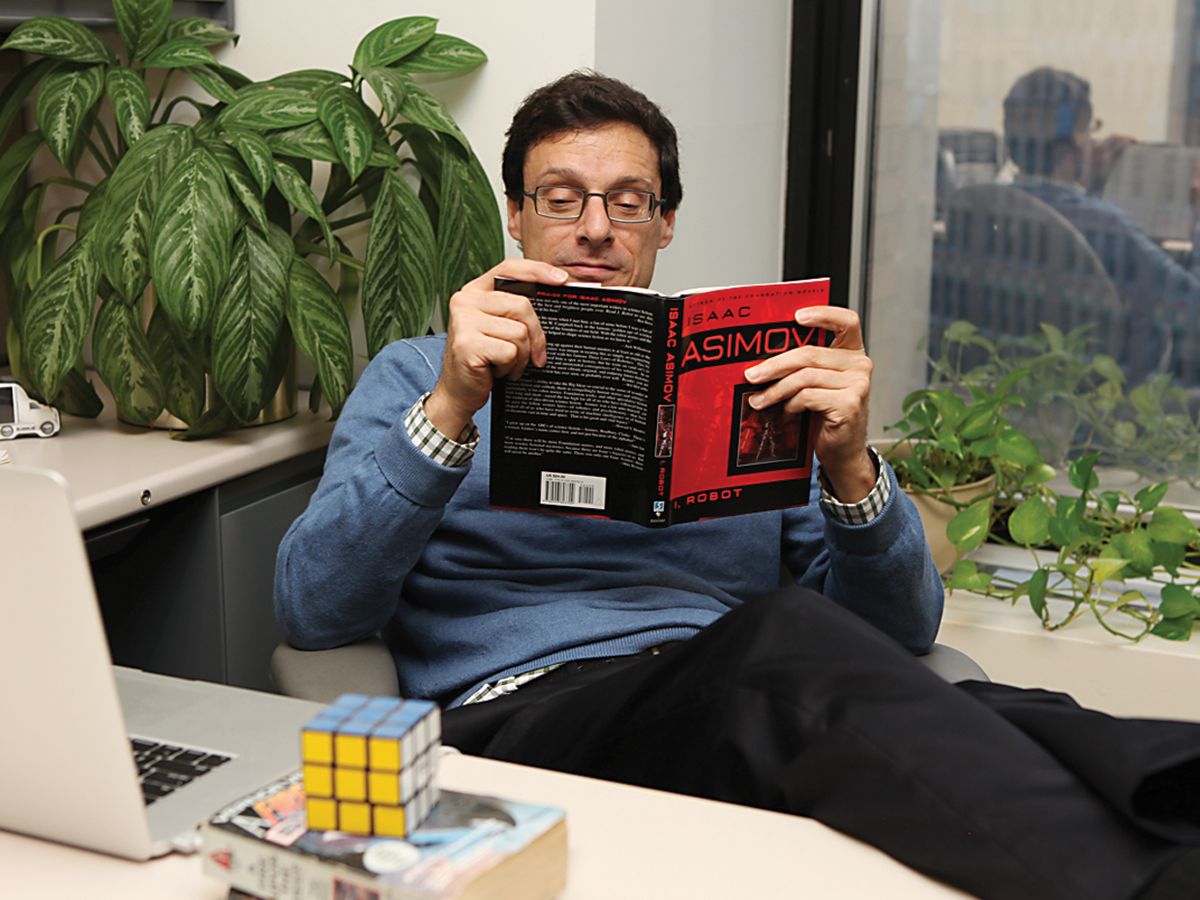

Shrewdly read short fiction (much quicker than novels): Stick to the “hard” stories about the future that engage the everyday issues of engineering. Avoid the popular fantasy species of science fiction, which is dominated by improbabilities and ruled by magical thinking. For guidance, look to David Hartwell and Kathryn Cramer’s annual anthology of stories that feature vexing questions about plausible future devices and alternative technological systems. A weightier volume is The Wesleyan Anthology of Science Fiction, which contains 52 short stories published from 1844 to 2008.

Imagine a revolutionary gadget that could plausibly be designed and built and inject it into the world as we know it today. Focus on a single character’s struggles to cope with the invention, maybe the inventor himself. For an example, watch the film Limitless (2011). The lead character discovers a new drug that enhances cognition so dramatically he risks all to keep it to himself.

Choose your medium. Given the advances in multimedia, producing short documentaries and animations is faster, easier, and cheaper than ever. After writing a rough draft, turn it into a visual experience. For inspiration, read the delicious tale “Rogue Farm” (2003), about agro-technology gone amok, and then view the 25-minute animated version created by Scottish TV in 2005.

In the end, when engineers confront and create fiction about the future, they face their own hopes and fears, appetites and longings. More than any work of art, the value lies in this encounter with the unknown.

About the Author

G. Pascal Zachary is a professor of practice at the Consortium for Science, Policy & Outcomes at Arizona State University. He is the author of Showstopper!: The Breakneck Pace to Create Windows NT and the Next Generation at Microsoft (The Free Press, 1994), on the making of a Microsoft Windows program, and Endless Frontier: Vannevar Bush, Engineer of the American Century (The Free Press, 1997), which received IEEE’s first literary award. Zachary reported on Silicon Valley for The Wall Street Journal in the 1990s; for The New York Times, he launched the Ping column on innovation in 2007. The Scientific Estate is made possible through the support of Arizona State University and IEEE Spectrum.