What is digital culture? It’s the websites and videos and images stored by museums, dance companies, libraries, music collections, and a whole host of arts and other organizations that represent a country’s social heritage.

That’s how Quinn Dombrowski defines it. And she and 1,300-plus other volunteers are scrambling to save the digital culture of Ukraine before the servers and personal computers that house them are destroyed.

The effort started shortly after the beginning of the Russian invasion of Ukraine. Anna Kijas, a librarian at Tufts University, tweeted on Saturday, 26 February, about an upcoming data-rescue event aimed at working to save Ukrainian websites. The event, scheduled for early March, was to be modeled after the 2017 data-rescue work that had been triggered by concerns about what would happen to certain government websites under the Trump administration.

Dombrowski, who is an academic technology specialist at Stanford University, thought that even a week was too long to wait. She reached out to Kijas on Twitter, along with Sebastian Majstorovic, an IT consultant at the Austrian Centre for Digital Humanities and Cultural Heritage, who had offered his services in response to Kijas’s initial tweet.

The three met via Zoom on Monday, just two days later. They were joined by an invited handful of others with an interest in supporting Ukraine who could offer cloud storage and other technical assistance. By the end of Tuesday, the three had planned their approach, developed tutorials, and built a website, and launched the project as SUCHO (Saving Ukrainian Heritage Online) the next day. By the next evening they had signed up more than 400 volunteers. A week later, the volunteer army numbered more than 1,000.

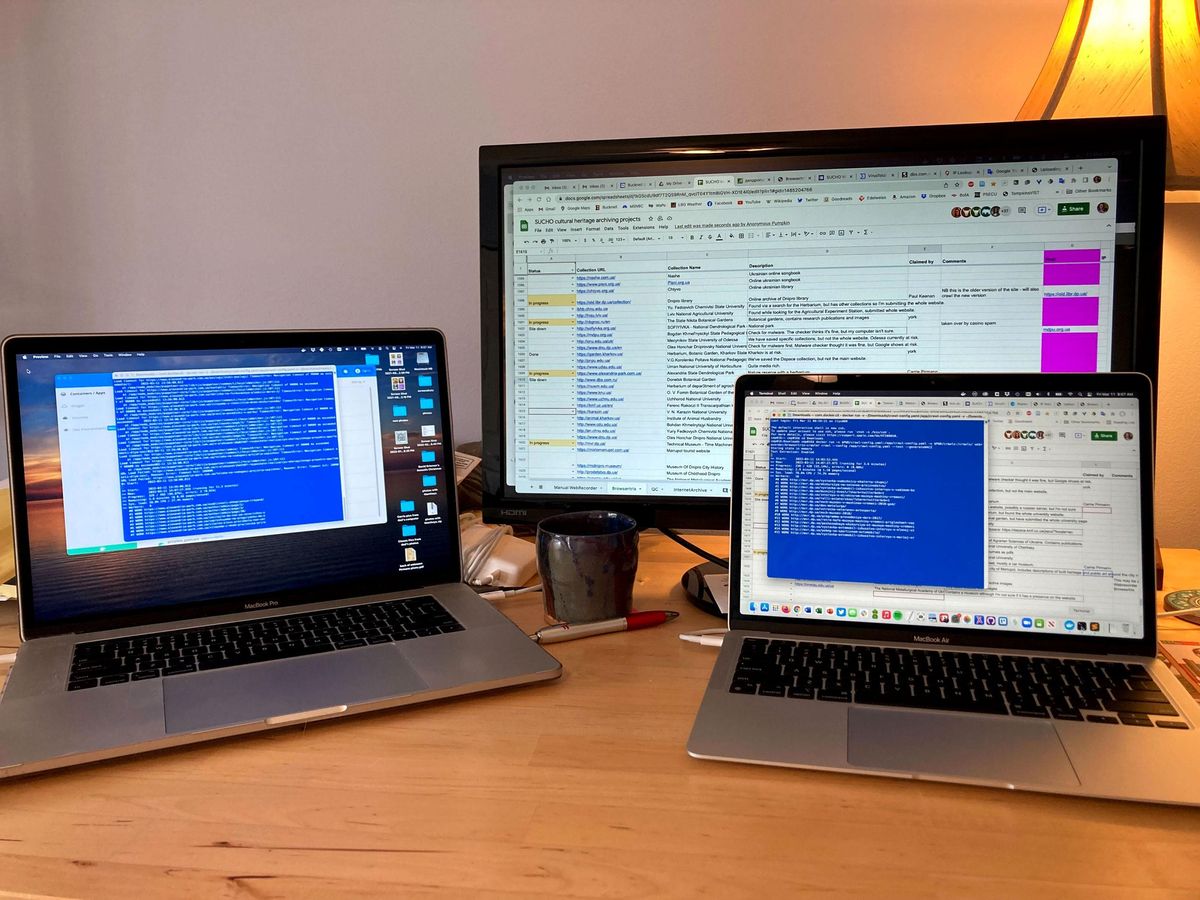

At this count, SUCHO has more than 1,300 active volunteers and more on a waiting list. The organizers have no official institutional sponsor. Dombrowski indicated that efforts with SUCHO have essentially hijacked her day job, and Stanford is supportive.

The organization has received a few grants —from the Association for Computers and the Humanities (ACH), the European Association of Digital Humanities, and Europeana—to support the effort, money that goes to things like server costs. The group is now raising funds for a part-time support engineer to actively help volunteers troubleshoot the open-source tools that they are using.

To date, SUCHO has saved more than 10 terabytes of data, including almost 15,000 images and PDFs, and parts of more than 3,000 websites.

“We’ve seen sites go down shortly after we finished archiving them.”

SUCHO volunteers initially found target content in the obvious places—museums, libraries, and large cultural institutions. But the volunteers have also been searching what Dombrowski calls the “back alleys” of the Internet by virtually walking city streets via Google Maps looking for storefronts of cultural organizations that might have stored materials in digital form. For example, small dance studios that teach children might have archives of performance videos or art galleries may store digital catalogs.

“There’s a beautiful site from the city of Sumy that has after-school and weekend programs that teach children about nature, the Ukrainian language, and Ukrainian identity,” Dombrowski says. “There’s a museum in Novgorod-Siversky dedicated to an epic medieval poem called ‘The Song of Igor’s Campaign.’ This one spoke to me personally—I had studied this poem in grad school. It isn’t an organization with the most resources, but it had pictures, and you could see the events they had held.”

Once SUCHO volunteers identify these resources, they are saving them in variety of ways.

In some cases, they add them to a list of relevant URLs that is submitted to the Wayback Machine, the website recording effort that’s been underway since 1996 by the nonprofit Internet Archive. (This nonprofit also has its own effort afoot to archivally store as much of the Ukrainian Internet as possible, as rapidly as possible.)

Volunteers are using the open-source archiving tools from Webrecorder along with their own storage systems, including servers, laptops, and Raspberry Pi–driven hardware (check out how you can build your own such system here). Recently, the group has started using Webrecorder’s cloud utility, which makes it possible to archive a website simply by filling out a Web form. The process is so easy that volunteers’ children have been able to help, and Dombrowski even organized an event at her local elementary school for more families to participate.

The biggest challenge for the group, Dombrowski says, is time.

“We’ve seen sites go down shortly after we finished archiving them, and sites that we’ve missed,” she said at a recent event hosted by the Internet Archive. “It’s a race against time.” To get an edge in this race, SUCHO volunteers are monitoring the situation on the ground and focusing their efforts on areas with active fighting where servers are at most risk.

The group also is rushing to train volunteers, without taking too much time away from their direct archiving efforts.

To participate in this effort, join the standby volunteer list.

Update 11 April 2022: Today, Amazon announced that it would cover the cost of cloud storage for SUCHO's effort as part of the AWS Open Data Sponsorship Program.

- How the Wayback Machine Is Saving Digital Ukraine - IEEE Spectrum ›

- Back From the Past: Stanford Resurrects First U.S. Website - IEEE ... ›

Tekla S. Perry is a senior editor at IEEE Spectrum. Based in Palo Alto, Calif., she's been covering the people, companies, and technology that make Silicon Valley a special place for more than 40 years. An IEEE member, she holds a bachelor's degree in journalism from Michigan State University.