8 July 2004--This month, a 3000-meter-high antenna will rise over Atlanta, but area residents might not notice. The antenna won't be a metal rod at the end of a hulking tower, but a solar-powered, helium-and-nitrogen�filled airship that will receive signals from nearby ground stations and rebroadcast them over the Atlanta metropolitan area.

The test transmission of voice, data, and video in many standard forms will be part of a demonstration planned by a local company, Sanswire Networks LLC, to show that high-altitude platforms-- or HAPs as they are known in the telecommunications world-- can work as mid-air base stations for wireless communications.

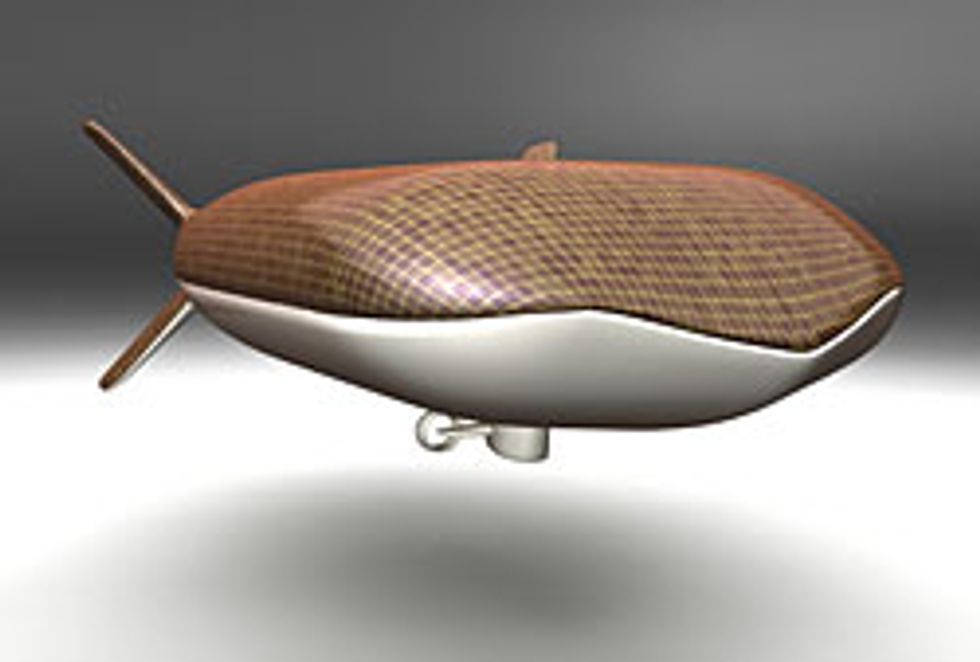

Sanswire's Stratellite:

which closely resembles a whale out of water, has been flattened in order to make more of its surface area upward facing. This has significantly increased the area covered by solar arrays [shown as brown and green grid] that provide power for propulsion and for running the onboard communications payload.

The Atlanta demo is a proof-of-concept designed to satisfy certain technical and regulatory concerns. It's a warm-up for what will be an even more important test of an actual commercial system. In the full-scale version, a larger airship, already designed, will float into the stratosphere and hold its position at 20 000 meters. At that altitude, a single ship's coverage area will be about 337 000 square kilometers , an area roughly the size of Germany. Thirteen airships working together could reach all points in the continental United States.

The Sanswire projects are representative of work being done on high-altitude communications platforms by companies and consortia around the globe. The reason using balloons or solar-powered drones for communications seems so attractive to so many experts is that these platforms combine the best features of satellite and terrestrial systems. They should be considerably cheaper than satellites to launch, retrievable so that updated equipment can be installed, and remotely controlled for placement where they would be most effective. And, in contrast to ground-based antennas, the high-altitude platforms will have a direct line-of-sight to all receivers, covering a much greater area than an antenna tower could hope to reach.

Sanswire is confident that the technology to be used for this month's test also will work fine in the bigger commercial system. Perhaps the most challenging hurdle was the design of the balloon itself, which had to be changed so that one of two Kevlar envelopes containing the airship's lighter-than-air gases would accommodate enough solar cells on its surface to provide the requisite power. "We've solved the energy problem," Sanswire CEO Michael K. Molen boasted in a conversation with IEEE Spectrum." In fact, he said, the solar panels on their "stratellites"--so-called because they act like satellites but perch in the stratosphere--capture enough energy to run for 10 days with no light.

Molen acknowledged that an earlier design didn't draw enough energy from the sun's rays during the day to power the propellers that maintain the airship's position and run the onboard electronics after dark. But its latest design, which is reminiscent of a whale, yielded much more skyward-facing surface, 5400 square meters, and so, more energy [see illustration].

Based on its technical progress, Sanswire, which is a subsidiary of GlobeTel Communications Corp., Pembroke Pine, Fla., has been busy working out agreements with communications companies in Australia, Europe, South America, the Caribbean, and Russia. Molen told Spectrum that the Australian government is serious about its push to provide broadband access to its 20 million residents. The fact that Australians are spread over an area roughly the size of the United States makes landlines and even terrestrial wireless base stations impractical, and the government is highly motivated to take a chance on something unorthodox, he says.

By early September, Sanswire's Australian subsidiary will start building the full-size airship designed to remain at 20 000 meters for 18 months at a time. It is intended to come down only when technological advances make the onboard equipment outmoded. Molen told Spectrum that Sanswire expects to launch the stratellite by the third quarter of 2005.

Such is the enthusiasm for high-altitude platforms that even setbacks and failures have not dampened its popularity. Sky Station International, the HAPs communications and surveillance company started by former U.S. Secretary of State Alexander Haig, ran out of funding before getting its plan off the ground, apparently the victim of an overly optimistic business plan. Perhaps the best-known effort, that of AeroVironment Inc., Monrovia, Calif., and its subsidiary, SkyTower Telecommunications, suffered a serious setback when its experimental solar-powered flying wing, Helios, crashed off the coast of Hawaii in June 2003. (Before it crashed, Helios made a record-setting 18-hour flight and cruised at 23 000 meters. )

With reverses of that kind looked upon as merely momentary, there has been no end to the rush of companies looking to get into the business. One of the more advanced and well-funded projects is SkyLINC Ltd., based in York, England. It has the backing of Capanina, a European Union project aimed at providing "broadband for all." Its concept is to use a balloon stationed 1600 meters above a large city and tethered to a ground station by a cable containing a fiber-optic line. SkyLINC says that a constellation of 18 such stations would be enough to cover the United Kingdom.

Other firms around the world are trying to get airborne as well, including San Diego-based General Atomics Aeronautical Systems, Italy's space agency ASI, and Canada's 21st Century Airships Inc.

Globally, the high-altitude concept got a big boost last year when certain regulatory hurdles, notably bandwidth allocation, were settled for over 50 countries. Resolutions were adopted at the 2003 World Radiocommunications Conference in Geneva that gave countries in the Americas the right to assign frequencies in two nonadjacent bands between 28 and 31 gigahertz for this purpose, with African, Asian, and European nations getting permission to use these frequencies on a case by case basis. [See "Radio Days: World Radio Communication Conference Concludes Work in Geneva," by Giselle Weiss:

As for the United States, Sanswire's test this month will be a significant stage in an ongoing project aimed at convincing the U.S. Federal Aviation Administration (FAA), which oversees travel across the nation's airspace, that its kind of system is ready for prime time. The FAA will have to be satisfied that an onboard Global Positioning System meant to keep the aircraft in a tightly defined space is as effective as advertised.

Sanswire is also looking to prove the effectiveness of transponders that will continually report the lighter-than-air vehicles' position to air traffic controllers. Though the aircraft would come to rest at altitudes well above the 12 000-meter ceiling at which the U.S. air traffic control system ends, the vehicles still have to get approval for ascent and descent.

Commercial introduction of communications services using high-altitude platforms will not take off in the United States until the current rules--mandating a long lead time before an individual unmanned flight is approved--are changed. After all, one of the selling points of platform-based communications is the ability of a plane or airship to be moved into place within a few hours' notice to provide extra bandwidth for such big events as the Olympic Games or the Super Bowl. Or an airship could act as a temporary replacement for infrastructure knocked out of service by a calamity, such as the collapse of New York City's World Trade Center.

A faster "on-ramp to the skies" for unmanned aircraft, including the kinds that could be employed in communications systems, is the goal of the Access5 initiative. The project is headed by NASA, consists of the U.S. Department of Defense and an aerospace industry group including Boeing, Lockheed Martin, Northrop Grumman, and AeroVironment as partners, and involves the FAA in an advisory role. Access5 is trying to establish a protocol permitting unmanned aircraft to simply take off from designated airports upon the filing of a flight plan with the FAA.

By 2009, the group hopes that file-and-fly operation will be firmly established. So far, NASA has allocated about US $100 million of the $360 million analysts say it will cost to carry out the systems development and testing that will satisfy the FAA. Technologies being worked on by the group include onboard collision-avoidance systems that, in tests conducted in April 2003, detected the presence of aircraft it deemed likely to cross into its safe zone while they were as far as 10 km away.