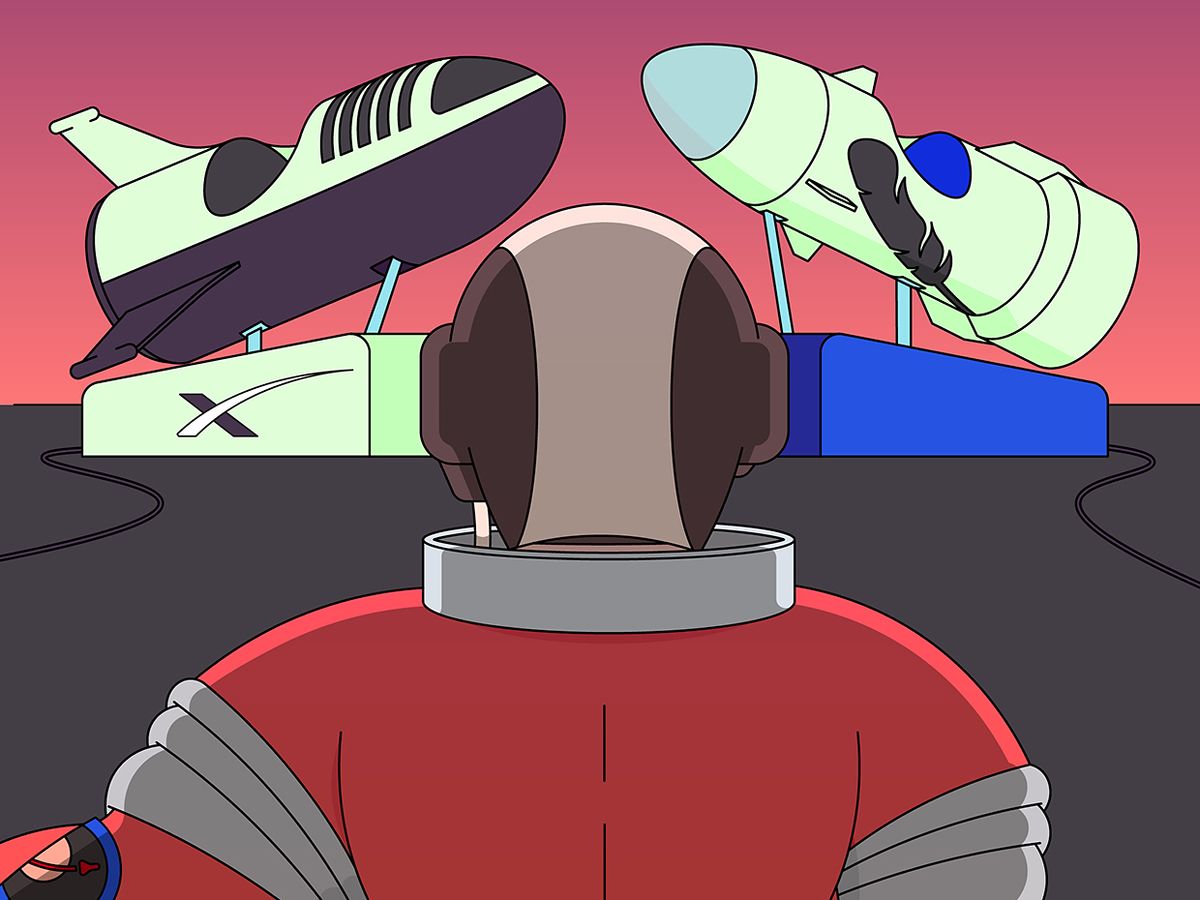

Musk vs. Bezos: The Battle of the Space Billionaires Heats Up

SpaceX and Blue Origin compete to commercialize Earth orbit and beyond

The commercial space business has blossomed over the past decade. Two companies, though, have grabbed the spotlight, emerging as the most ambitious of them all: Blue Origin and SpaceX.

At first glance, these two companies look a lot alike. They are both led by billionaires who became wealthy from the Internet: Jeff Bezos of Blue Origin earned his fortune from Amazon.com, and Elon Musk of SpaceX got rich initially from Web-based businesses, notably PayPal. Both companies are developing large, reusable launch vehicles capable of carrying people and satellites for government and commercial customers. And both are motivated by almost messianic visions of humanity's future beyond Earth. This coming year, we'll likely see some major milestones as these two titans continue to jockey for position.

Over the past few years, SpaceX has become one of the most active launch companies on the planet. In 2018 alone, SpaceX performed 21 launches, representing about 20 percent of roughly 100 worldwide launches.

The company stands out in another way—it's the only one to recover and reuse its rockets. Landings of its Falcon 9 first stages have gone from being novelties, often with explosive failures, to a routine aspect of most missions. Last May, SpaceX introduced its latest version of the Falcon 9, called the Block 5, the first stage of which is designed to be flown 10 or more times.

Although the Falcon 9 will be SpaceX's workhorse for years to come, the company added a new vehicle to its stable three months before introducing the Block 5. Last February, the company launched the first Falcon Heavy, which includes three Falcon 9 first stages lined up in a row. The Falcon Heavy is capable of placing more than 60 metric tons into low Earth orbit, far more than any existing launch vehicle can accomplish.

But even the Falcon Heavy pales in comparison with what SpaceX is now developing, a vehicle that until recently was called the Big Falcon Rocket, or BFR. (The R-rated interpretation of that acronym wasn't lost on the rocket's developers, who initially used it as the informal code name for the project.) In late November, Musk announced a name change for the BFR—to Starship for the crewed upper stage, and Super Heavy for the lower booster stage. That booster will have 31 of the company's Raptor engines, which are under development, while Starship will be outfitted with seven Raptor engines. Both stages are intended to be reusable, and Starship will be able to carry dozens of people to destinations far beyond Earth orbit.

SpaceX has modified the design of this colossal vehicle a couple of times since conceiving it in 2016. The most recent version was described at a press conference this past September at the company's California headquarters. This version, Musk said, would be able to place 100 metric tons on the surface of Mars, provided that the spaceship's upper stage was refueled in Earth orbit before departing for the Red Planet.

“I think it looks beautiful," he added, noting the similarity to a fictional rocket ship of graphic-novel fame. “I love the Tintin rocket design, so I kind of wanted to bias it towards that."

Speaking in early September at an event to celebrate the 60th anniversary of the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency, SpaceX's chief operating officer, Gwynne Shotwell, said that the company will begin making the first “hop tests" of the BFR's upper stage (Starship) in late 2019.

Blue Origin, by contrast, has yet to launch anything at all into orbit. But the company has similarly big ambitions. It's working on a rocket it calls New Glenn (named after John Glenn, the first American to orbit Earth), which is scheduled to launch for the first time in 2021. The two-stage rocket will be able to place 45 metric tons into low Earth orbit, with its first stage designed to land on a ship at sea and be reused up to 25 times.

“We're in build mode right now," said Bob Smith, CEO of Blue Origin, during a space policy workshop in Washington, D.C., this past October. The company has completed a new 70,000-square-meter (750,000-square-foot) factory for constructing the rocket just outside the gates of the Kennedy Space Center, in Florida, and it's currently building a testing and refurbishment facility nearby, which is expected to be completed in early 2019. Blue Origin is also modifying a dormant launchpad at nearby Cape Canaveral for its operations and has signed up several commercial customers for New Glenn.

Powering New Glenn will be an engine that Blue Origin has been developing called the BE-4. The company is also selling the engine to United Launch Alliance (ULA), a joint venture of Lockheed Martin and Boeing that was formed in 2006 to serve U.S. government customers. ULA will use the BE-4 on the first stage of its Vulcan rocket, a successor to its existing Atlas and Delta vehicles.

Last October, both Blue Origin and ULA received contracts from the U.S. Air Force to support development of their launch vehicles: $500 million for Blue Origin and nearly $1 billion for ULA. (SpaceX did not receive an award as part of this Air Force Launch Service Agreement program, although the company did not disclose whether it had even submitted a bid.) “It's exciting to see that we'll be powering two launch vehicles in the United States Air Force's arsenal for decades to come," Smith said at that workshop.

New Glenn builds on the lessons Blue Origin has learned with its suborbital tourist vehicle, New Shepard, named after Alan Shepard, whose 1961 suborbital trip made him the first American in space. New Shepard, featuring a reusable booster and capsule, is being tested at Blue Origin's West Texas launch site.

Blue Origin plans to fly passengers soon on New Shepard, which has room in the capsule for six people. Timing of the first tourist flight is unclear, though. “I'm hopeful it will happen in 2019," Bezos said when asked when commercial flights would start, during an interview at the Wired 25 conference last October. At the same time, he included the appropriate notes of caution: “I was hopeful it would happen in 2018. I keep telling the team that it's not a race. I want this to be the safest space vehicle in the history of space vehicles."

Unlike Blue Origin, SpaceX has no apparent interest in suborbital spaceflight and is focusing instead on sending people into orbit, most immediately using the Block 5 version of its Falcon 9 booster. SpaceX and Boeing both have NASA contracts to develop crewed spacecraft to transport astronauts to and from the International Space Station. Development of SpaceX's Crew Dragon, a variation of the Dragon spacecraft currently used for carrying cargo to the space station, is nearing completion. NASA released a schedule last October that calls for a final test flight of the Crew Dragon, with people aboard it for the first time, this coming June.

Blue Origin also anticipates flying people into orbit one day, on its New Glenn rocket. The company participated in earlier bidding rounds of NASA's commercial crew program and maintains an unfunded agreement with the agency, whereby NASA will provide technical support for Blue Origin's efforts in human spaceflight. “All of our early flights will be payloads," said Rob Meyerson, formerly the senior vice president of advanced programs at Blue Origin, speaking of the company's New Glenn rocket at a conference at MIT last March. “We'll evolve to flying people probably seven, eight years down the road."

Even further down the road, both Bezos and Musk see their companies truly enabling the expansion of humanity beyond Earth. But they have different visions of where we should go and how.

Musk has long talked about his desire to make humanity “multiplanetary" and thus not vulnerable to a calamity, natural or human-made, affecting Earth. We should try “to become a multiplanet civilization...to ultimately have life on Mars, the moon, maybe Venus, the moons of Jupiter, throughout the solar system," he said at the September press conference where he described the most recent version of the BFR.

His primary focus, though, has been on Mars. The design of the BFR has been based on its ability to take large amounts of cargo and people to the surface of Mars to establish settlements there. In a 2017 speech, he said the first BFR cargo missions to Mars could launch in 2022, followed by crewed missions in 2024, a schedule he acknowledged was “aspirational."

Yet Musk has shown an increasing interest in missions to other destinations, particularly the moon. At the September press conference, he announced that Japanese billionaire Yusaku Maezawa had paid for a BFR flight, scheduled for 2023, that will go around the moon. Maezawa, an art enthusiast who made his fortune in online fashion retailing, plans to fly on that mission accompanied by a small number of personally selected artists.

Musk has also suggested that the BFR could support permanent stations on the moon. “We should have a lunar base by now," he said in that 2017 speech, but he hasn't disclosed any details about who would build it, or how.

Blue Origin has a similar view of humanity's destiny. “Blue Origin believes in a future where millions of people are living and working in space," the company states on its website.

But Blue Origin has focused on going to the moon, not Mars, as an initial step beyond Earth. It has proposed developing a lunar lander called Blue Moon for delivering cargo and, eventually, people to the lunar surface. “At Blue, we believe there are certain steps that you have to take," Smith said. “We believe that the moon is the next logical step. It has resources. It is an incredible gift."

Bezos, a Princeton University alumnus, said he was inspired by Gerard O'Neill, a Princeton physicist who in the 1970s proposed the development of giant space settlements that could be home to thousands of people.

“My role is to help build that heavy-lifting infrastructure, because I have the financial assets to do that," Bezos said last May while accepting an award created in memory of O'Neill, from the National Space Society. “That will set things up for this dynamic entrepreneurial explosion that will lead to this Gerry O'Neill world."

Those financial assets are in the form of his stake in Amazon.com, which makes him the wealthiest man alive, worth more than $100 billion. He said he spends about $1 billion a year on Blue Origin and suggested at the Wired 25 conference last October that his outlays for the company may go up in 2019.

“Blue Origin is the most important thing I'm working on," Bezos said, “but I won't live to see it all rolled out." Musk, too, speaking about colonizing Mars, has said, “I probably won't live long enough to see it become self-sustaining." Clearly, these titans of today's gilded age are thinking hard about their legacies, which despite their many other accomplishments may end up being for what they do in space.

This article appears in the January 2019 print issue as “SpaceX and Blue Origin Face Off."