China’s moon lander is on its way. Today the Chinese space agency launched the lander into space aboard a Long March 3B rocket.

If all goes according to plan with the Chang’e-3 mission, the red flag of China will soon fly on the moon’s surface. The lander is expected to touch down on the lunar surface in about two weeks; then a rover will roll off the lander’s ramp and start making tracks in the regolith.

The landing is a complicated maneuver, and plenty could go wrong, experts say. However, if the mission is a success, it will be the first moon landing since the Russian Luna 24 mission in 1976.

China’s Chang’e program, named after a moon goddess, has already had several resounding successes. In the first mission, the lunar orbiter Chang’e-1 arrived in orbit in 2007 to take 3-D images of the lunar surface; it operated until 2009 when it made a deliberate crash landing.

Next up, in 2010, was the orbiter Chang’e-2, which tested several key technologies necessary for this month’s mission. Jiangchuan Huang of the Beijing Institute of Control Engineering presented the results of the 2010 mission at the International Astronautical Conference in Beijing this September. He says that one of those key technologies was the design of an Earth-to-moon flight trajectory that shaves eight days off the trip. The Chang’e-2 also demonstrated the braking maneuver that inserted the spacecraft into orbit at an altitude of 100 kilometers above the moon’s surface, an action the Chang’e-3 spacecraft will duplicate before descending to the ground.

The second-generation craft also took high-resolution images of the presumed landing spot for this year’s lander, a plain of basaltic lava in the northern hemisphere called Sinus Iridum. “Chang’e-2 made a solid foundation for China’s follow-on lunar exploration program,” Jiangchuan says.

China’s aerospace engineers had to master a number of new technologies for the Chang’e-3 mission, which were described in a recent report from the Beijing Institute of Spacecraft System Engineering. To land gently on the moon’s surface, the spacecraft will use thrusters to slow its descent until it reaches an altitude of 100 meters. The lander will hover there as it scans the terrain for hazards using optical and laser imaging, and then an autonomous system will determine the safest landing spot and guide the craft down. When the Chang’e-3 is only 4 meters from the ground, its engine will shut off and it will drop, protected by a landing cushion.

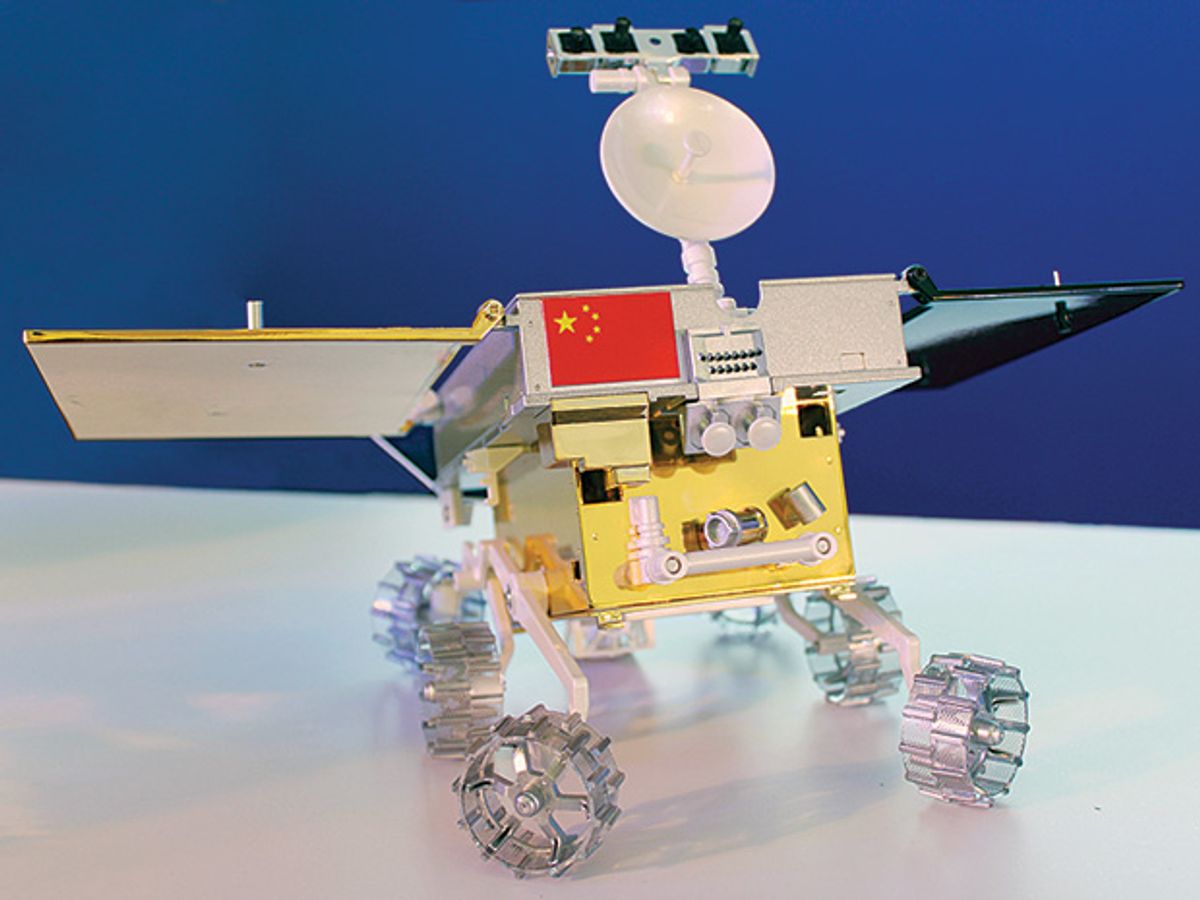

Once the spacecraft is safely settled, the rover will start exploring the landscape. While it will primarily be under the control of operators back on Earth, the six-wheeled, 140-kilogram rover has its own onboard intelligence. It will use its software to construct a 3-D map of the terrain, recognize hazards and obstacles, and plan its path to a target. The Chinese space agency has named the rover Yutu, meaning "jade rabbit," after the legendary companion of the moon goddess Chang'e.

Both the lander and the rover will do some science once they’re established, but the Chinese space agency hasn’t explained these scientific missions in detail. The lander is equipped with optical telescopes and an extreme ultraviolet camera for astronomical observations, while the rover carries infrared and X-ray spectrometers to study the chemical composition of rocks and soil.

Experts say the Chinese space agency has prepared carefully for the moon landing mission with extensive simulations, testing, and a tryout for the rover in a desert region of northwest China. “It’s something the Chinese haven’t done before, and they’ve gone to a lot of trouble to make sure it will work,” says Brian Harvey, author of the recent book China in Space. “But landing on [the moon] is hard!”

While much of the current attention is focused on the landing, Harvey says the science experiments that the lander and rover will perform may turn out to be just as interesting. “They’ve given us a 90-day roving period, but I don’t believe that at all,” he says. “I think it will go a lot longer than that.” He notes that NASA’s Mars rovers also had a 90-day mission plan, and yet one of them is still rolling after nearly 10 years of operation.

The next stage of China’s moon exploration program is a sample-return mission, scheduled for 2017. Many experts have speculated that a manned mission will follow in the 2020s, but the Chinese government hasn’t announced its intention to send a taikonaut to take that one big step for China.

This article originally appeared in print as "China’s Moon Machine."