12 August 2009—The Indian state of Punjab is considered to be the country’s breadbasket, producing about 1 percent of the world’s rice and 2 percent of its wheat, according to the Indian government. But Punjab might not retain its rank for long. According to data published this week in the journal Nature, the northwestern states of Haryana, Punjab, and Rajasthan lost about 109 cubic kilometers of groundwater between 2002 and 2008, or about three times the capacity of Lake Mead, the largest reservoir in the United States.

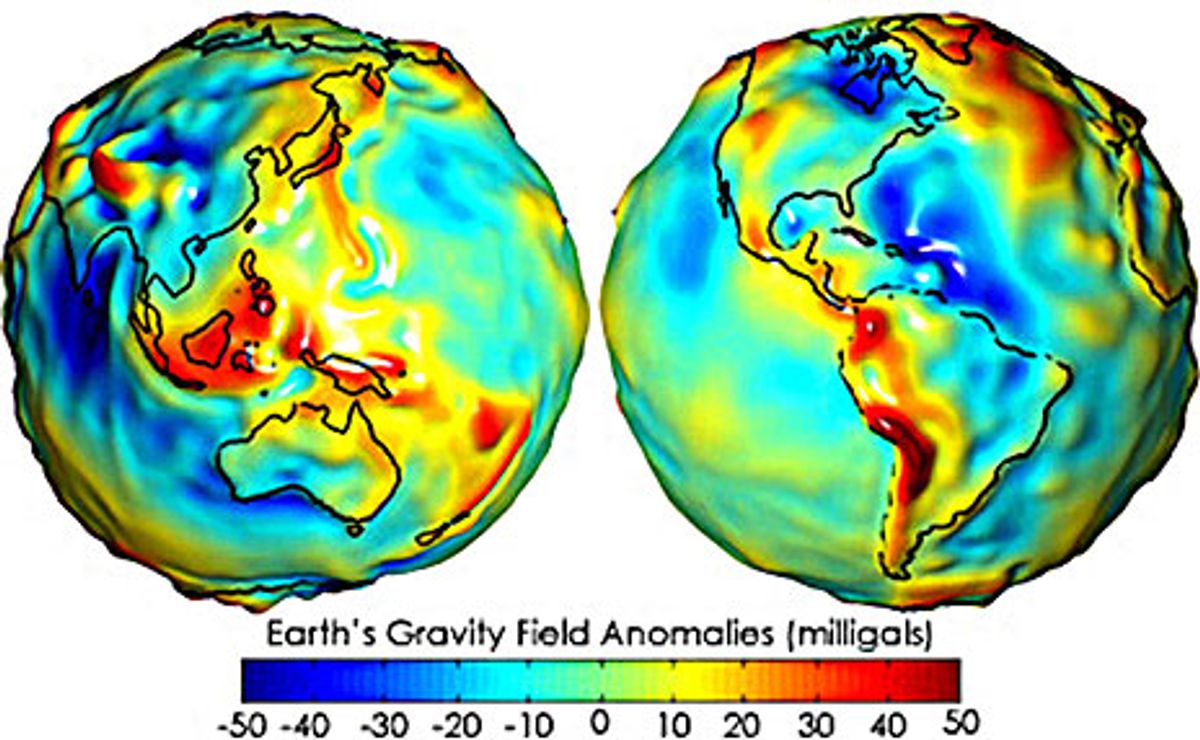

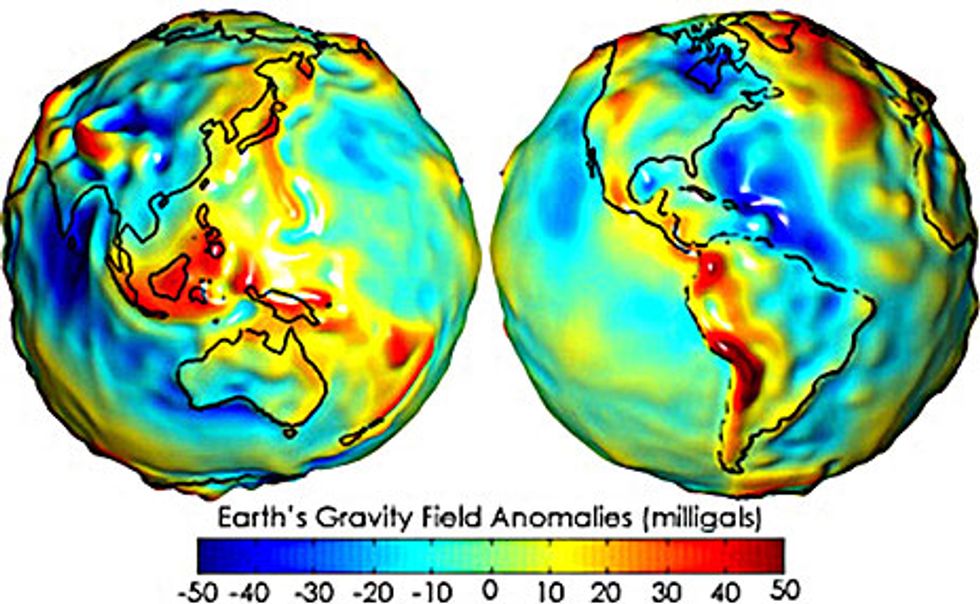

Scientists at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center and the University of California, Irvine, discovered the groundwater loss in new maps of the Earth’s gravity made using the twin satellites of the Gravity Recovery and Climate Experiment (GRACE) system. Unlike most Earth-observing satellites, GRACE doesn’t infer properties of the Earth’s surface from emitted or reflected radiation. Instead, the two satellites orbit in tandem, maintaining a distance between them of 220 kilometers. As the twin satellites fly, minor perturbations in the Earth’s gravity fields may cause the lead satellite to accelerate slightly before pulling the trailing satellite along and resuming the prescribed 220-km distance. A microwave ranging system on board GRACE tracks the minute changes in distance, and Global Positioning System receivers can pinpoint the location of the satellites over Earth with high precision. By constantly measuring the distance between the two satellites, the system can generate sufficient data to produce maps of the Earth’s gravity anomalies each month. Any changes in the mass of the land beneath the satellites over time are reflected in subsequent flights over the region.

Illustration: NASA

The calculation of the gravitational pull on the GRACE satellites has turned out to be an unusual and useful tool for hydrologists. Mining large quantities of water from underground aquifers decreases the Earth’s mass at that location, thus affecting the Earth’s gravity. Indeed, the biggest gravity anomalies GRACE picks up are changes in water, says Matthew Rodell, a scientist at the Goddard Institute for Space Studies. Along with Isabella Velicogna and James Famiglietti at the University of California, Irvine, he examined seasonal variations in lake and river levels, the potential influx of water from glaciers melting in the Himalayas, and soil moisture levels from rainfall to rule out the possibility that natural variation accounts for the changes in the quantity of water in the regions, and therefore the effect on the satellites.

“After the crumbling of the ice sheets in Greenland and the Antarctic, this region was like a big bull’s-eye in our data,” says Rodell.

Groundwater accounts for almost half the water used in irrigation and the majority of water consumed domestically in these three Indian states. The water lies in the Indus River plain aquifer and smaller neighboring stores of groundwater. The GRACE data indicated that between August 2002 and October 2008, 17.7 km3 of water were withdrawn each year, far exceeding the natural rate at which water reenters the aquifers.

“It’s very difficult for us to get information on groundwater depletion in developing countries, so any remote approach that can monitor it is extremely useful, and GRACE provides that,” says Bridget Scanlon, a hydrogeology professor at the University of Texas, Austin, who was not involved in the research. That information is sorely needed: Irrigated agriculture was responsible for most of the global freshwater resources consumed in the last century, she says. “If we don’t get a handle on this, our existing agriculture will simply be unsustainable.”

Moving away from water-intensive crops such as rice, which often requires flooding fields a meter deep, could potentially curb the stark rate of loss, Rodell suggests. ”My hope is that the Indian government will use this study as evidence to bolster their plans to reduce groundwater consumption and get to a more sustainable solution.”