More than two months after Hurricane Maria devastated Puerto Rico, large sections of the island have yet to have electricity restored. The state of the power grid is still so unstable that even those areas that have been re-electrified can’t really count on around-the-clock power.

As many observers have noted, this is an untenable situation. I’ve worked for much of my adult life as a solar engineer, installing solar microgrids in remote parts of the world that previously had no access to electricity. But Puerto Rico is different. All over the island, people have relied for decades on steady, abundant electricity and the modern conveniences that come with it. And so to suddenly not have electricity presents all kinds of hardships—some obvious and some less so.

For me personally, this ongoing hardship is especially wrenching. I grew up in Puerto Rico, in the rainforest of El Yunque and on the beaches of Luquillo, and much of my family is still there. Immediately after the storm, I couldn’t reach any of them because of course they had neither power nor phone service. When officials announced that power wouldn’t be restored for months, I booked the earliest flight to San Juan that I could find. I spent a week in Puerto Rico in early October, checking on relatives and friends and helping where I could.

My time there veered from the absurd to the devastating. Several times a day, I’d manage to walk into a room, flick on the light switch, and then laugh at myself for having forgotten—again. There were emergencies happening seemingly everywhere I turned—people needing medical help they couldn’t get, others unable to work or go to school, businesses unable to stay open. Since my return to New York, I’ve been working hard to get the word out about conditions on the ground there. Here are seven facts about living in Puerto Rico right now.

1. Stoplights don’t work

Driving around after the storm was chaotic. Every intersection became a test of wills—the bold and reckless forged ahead, heedless of cross traffic, the meek waited for a break in traffic to make their move. Although a few of the busier intersections had traffic cops, the vast majority didn’t. And the cops who had to stand out in the sun and the heat all day serving as stoplight replacements clearly were having a rough time. Did I mention there was a heat wave right after the storm?

2. ATMs and credit cards don’t work

Puerto Rico has a modern banking system, but after the storm hit, many ATMs didn’t work at all for lack of power. Those that were still operating quickly ran out of money. Without money, consumers couldn’t buy anything, and businesses couldn’t sell anything. And of course credit cards didn’t work because there was no way to process transactions. The economy basically ground to a halt.

Businesses that did manage to stay open relied on generators and cash. Even then, it was a struggle. One day, I and some friends were having lunch at my favorite restaurant, Toro Salao, when the manager informed us that we were eating the last of the tostones, a delicious alternative to French fries made from plantains. The storm had knocked down nearly all of the island’s plantain trees.

3. Cellphones don’t work

Before the hurricane, the island enjoyed decent cellphone coverage pretty much everywhere. The storm knocked out 95 percent of Puerto Rico’s cell service [PDF], according to the U.S. Federal Communications Commission. Throughout my stay, phone service remained down across most of the island, with only limited service within San Juan and a few other spots. Restoring phone service will mean not just repairing cell towers that were damaged but also electrifying them.

For most people I met, lack of communication was the single biggest source of stress. Going days on end without knowing whether family members were okay is something that no one should have to go through.

I did manage to place a few calls either with a satellite phone or by calling when I happened to drive through an area that had reception. It’s hard to describe that intense feeling of relief when you do finally hear from a loved one. I went through it myself when I got word that my parents and brothers were okay. I experienced an entirely different set of emotions when I learned that my favorite uncle had passed away right after the storm. By the time I found out, he had already been dead a week.

4. Water doesn’t work

It takes electricity to run the pumps that move water through the system, and it takes electricity to filter and treat the water so that it’s safe to drink. I visited some towns that had diesel-powered emergency generators to get the water flowing again. But much of the island’s infrastructure was so badly damaged that even now, many places still lack clean running water. The water crisis has in turn prompted medical experts to warn of a looming health crisis in Puerto Rico.

5. Refrigeration doesn’t work

No electricity means your fridge soon becomes just a big box with rotting food inside. As temperatures climb, food quickly goes bad, and so people are forced to shop for food every day. During my visit, supermarkets that were still open had long lines of people standing in the sun, waiting to shop for a very limited selection of goods. Ice is therefore in high demand, to keep food and drinks cool a little longer and maybe postpone another punishing trip to the store.

6. It’s dark

No street lights or house lights or lights of any kind means the nights are really dark. I’ve camped in the desert before, but this was a different kind of dark. Trying to drive at night was surprisingly difficult—street signs were hard to read, buildings were indistinguishable from one another, and the usual landmarks weren’t at all obvious.

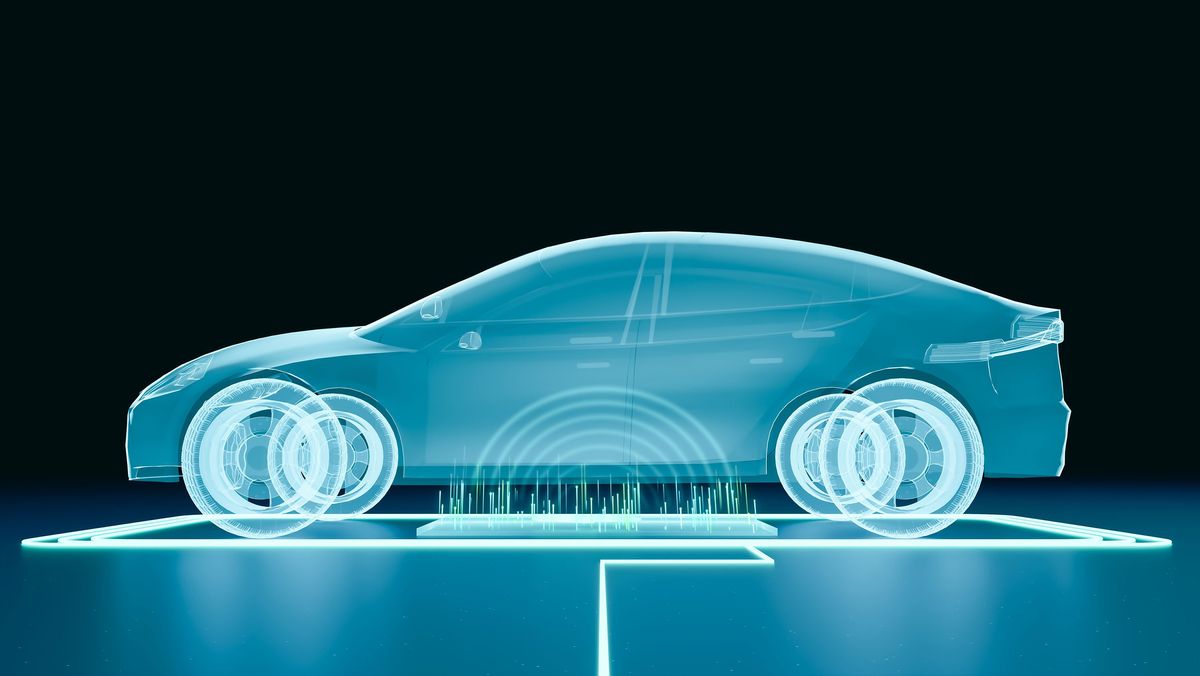

7. Solar power works!

Fortunately, my experience designing and installing solar microgrids for rural villages in Haiti, India, and sub-Saharan Africa, and urban rooftops in New York City came in handy. Before my trip, I’d collected money via a crowd-sourcing fundraiser, and I arrived in Puerto Rico with a suitcase full of portable solar panels designed by Voltaic Systems of Brooklyn, N.Y., suitable for charging cellphones and other small devices. I also brought LED lights, water filters by LifeStraw, and CampStoves by Biolite. As I traveled around the island, I gave the equipment to people I met. The recipients were invariably overwhelmed and grateful, and I felt lucky to be able to offer them the means to connect with their loved ones, drink clean water, and prepare a meal.

There is still so much work to do. I’m back home in Brooklyn but I can’t rest. Having worked in the energy industry for a long time, I know that I can make a difference, helping to build a cleaner, more resilient power system for Puerto Rico. If you have a technical background, please consider using your expertise to help others who really need it.

About the Author

John Humphrey was born and raised in Puerto Rico. He now lives in Brooklyn, N.Y., and has been working with solar equipment since 2001. He’s currently developing solar-powered community centers to help re-electrify and rebuild communities in the Caribbean that were devastated by the recent hurricanes. You can read about his projects here, and you can donate to the solar Gazebo Community centers project here. His recent trip to Puerto Rico was documented in “After Maria: A Puerto Rico Story,” produced by Praytell Films.