Lidarland is buzzing with cheap, solid-state devices that are supposedly going to shoulder aside the buckets you see revolving atop today’s experimental driverless cars. Quanergy started this solid-state patter, a score of other startups continued it, and now Velodyne, the inventor of those rooftop towers, is talking the talk, too.

Not Luminar. This company, which emerged from stealth mode earlier this month, is fielding a 5-kilogram box with a window through which you can make out not microscopic MEMs mirrors, but two honking, macroscopic mirrors, each as big as an eye. Their movement—part of a secret-sauce optical arrangement—steers a pencil of laser light around a scene so that a single receiver can measure the distance to every detail.

“There’s nothing wrong with moving parts,” says Luminar founder and CEO Austin Russell. “There are a lot of moving parts in a car, and they last for a 100,000 miles or more.”

A key difference between Luminar and all the others is its reliance on home-made stuff rather than industry-standard parts. Most important is its use of indium gallium arsenide for the photodetector. This compound semiconductor is harder to manufacture and thus more expensive than silicon, but it can receive at a wavelength of 1550 nanometers, deep in the infrared part of the spectrum. That makes this wavelength much safer for human eyes than today’s standard wavelength, 905 nm. Luminar can thus pump out a beam with 40 times the power of rival sensors, increasing its resolution, particularly at 200 meters and beyond. That’s how far cars will have to see at highway speeds if they want to give themselves more than half a second to react to events.

Russell’s a little unusual for a techie. He stands a head taller than anyone at IEEE Spectrum’s offices and, at 22, he is a true wunderkind. He dropped out of Stanford five years ago to take one of Peter Thiel’s anti-scholarships for budding businessmen; since then he’s raised US $36 million and hired 160 people, some of them in Palo Alto, the rest in Orlando, Fla.

Like every lidar salesman, he comes equipped with a laptop showing videos taken by his system, contrasted with others from unnamed competitors. But this comparison’s different, he says, because it shows you exactly what the lidar sees, before anyone’s had the chance to process it into a pretty picture.

And, judging by the video he shows us, it is very much more detailed than another scene which he says comes from a Velodyne Puck, a hockey-puck-shaped lidar that sells for US $8,000. The Luminar system shows cars and pedestrians well in front of the lidar. The Puck vision—unimproved by advanced processing, that is—is much less detailed.

“No other company has released actual raw data from their sensor,” he says. “Frankly there are a lot of slideshows in this space, not actual hardware.”

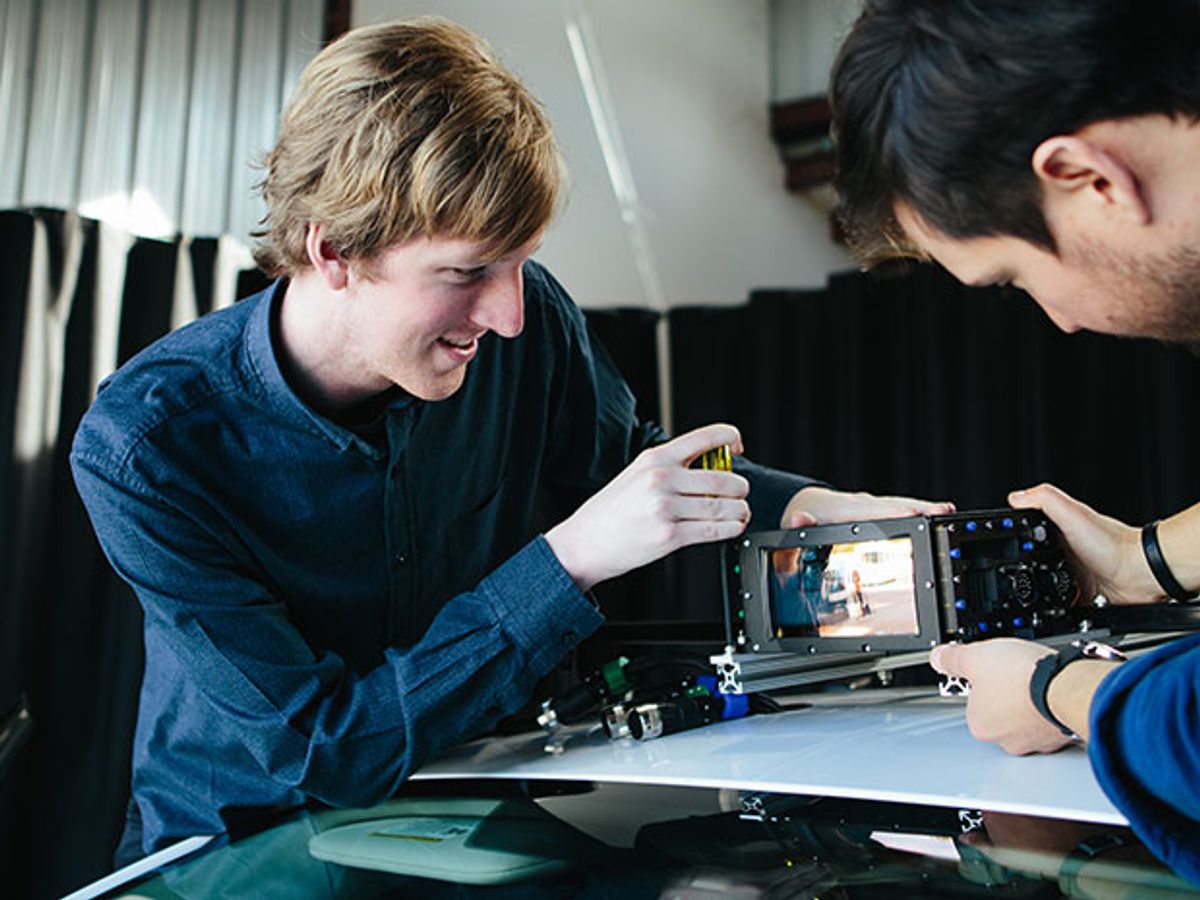

We take the gizmo into our little photo lab here and our photo editor snaps a few, always taking care not to look too deeply into the window shielding the lidar’s mirrored eyes. Trade secrets, all very hush-hush. One thing’s for sure: The elaborate optics don’t look cheap, and Russell admits it isn’t, not yet.

These machines are part of a total production run of just 100 units, enough for samples to auto companies, four of which, he says, are working with it as of now. He won’t say who, but Bloomberg quotes other sources as saying that BMW and General Motors “have dropped by” the California office.

The cost per unit will fall as production volume rises, he says. But he isn’t talking about $100 lidar anytime soon.

“Cost is not the most important issue; performance is,” he contends. “Getting an autonomous vehicle to work 99 percent of the time is not necessarily a difficult task, it’s the last percent, with all the possible ‘edge cases’ a driver can be presented with—a kid running out in front in the road, a tire rolling in front of the car.”

Tall though he is, Russell is himself a prime example of a hard-to-see target because his jeans are dark and his shirt is black. “Current lidar systems can’t see a black tire, or a person like me wearing black—Velodyne’s [Puck] wouldn’t see a 5- to 10-percent reflective object [30 meters away]. It’s the dark car problem—no one else talks about it!”

And, because the laser’s putting out 40 times more power, a dark object at distance will be that much easier to detect.

What’s more, only one laser and one receiver are needed, not an array of 16 or even 64—the count for Velodyne’s top-of-the-line, $50,000-plus rooftop model. As a result, the system knows the source for each returning photon and can thus avoid interference problems with oncoming lidars and with the sun itself. But, because it hasn’t got the 360-degree coverage of a rooftop tower, you’d need four units, one for each corner of the car.

That, together with the need to make the laser, receiver, and image processor at its own fab, in Florida, means the price will be high for a while. Russell’s argument is simple: good things cost money.

“The vast majority of companies in this space are integrating off-the-shelf components,” he says. “The same lasers, same receivers, same processors—and that’s why there have been no advances in lidar performance in a decade. Every couple of years a company says, ‘we have new lidar sensor, half the size, half the price, and oh, by the way, half the performance.’ The performance of the most expensive ones has stayed the same for practically a decade; all the newer ones are orders of magnitude worse.”

Philip E. Ross is a senior editor at IEEE Spectrum. His interests include transportation, energy storage, AI, and the economic aspects of technology. He has a master's degree in international affairs from Columbia University and another, in journalism, from the University of Michigan.