More than 300 employees of Silicon Valley companies gathered last Friday night in Palo Alto to share war stories and to start developing what organizers called a "Startup Employee Equity Bill of Rights".

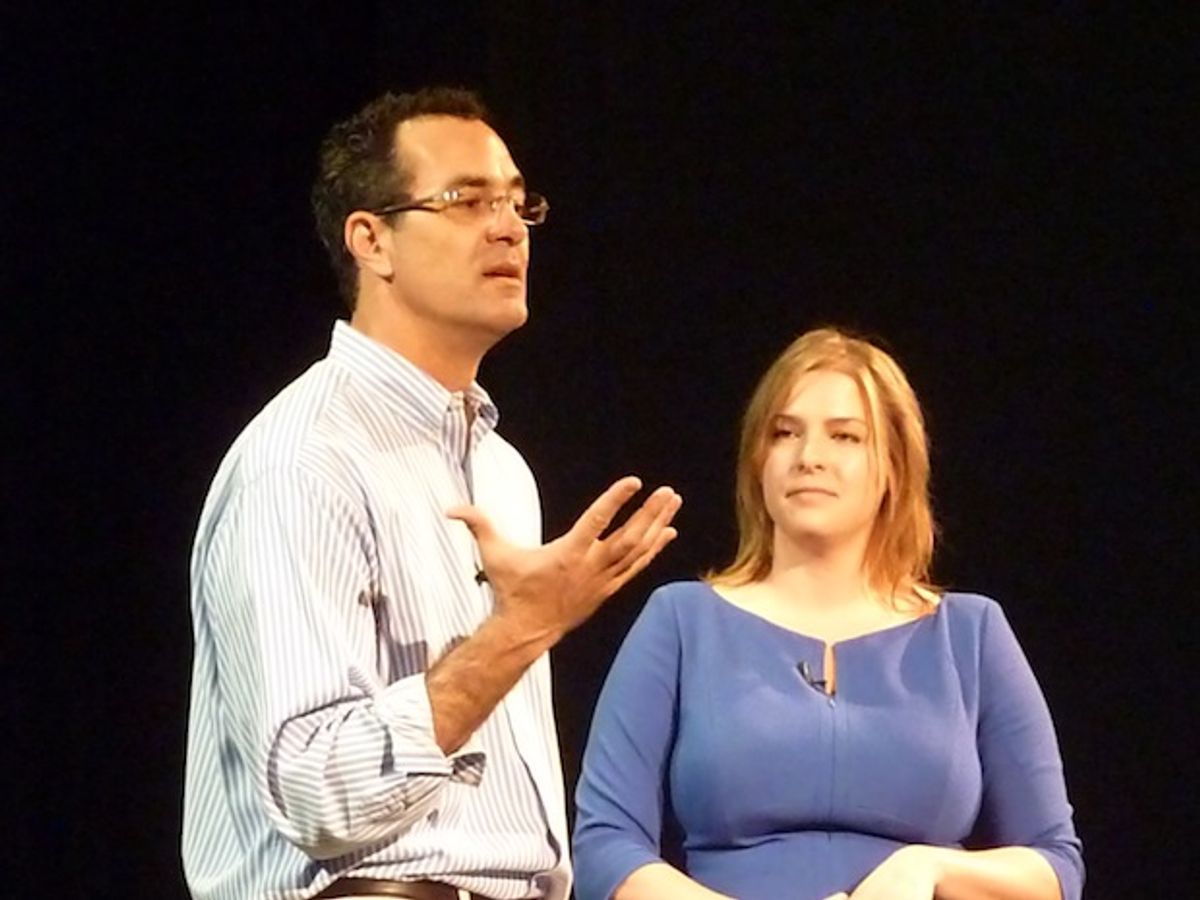

Mary Russell, an attorney, and Chris Zaharias, who ran tech sales teams at a number of start-ups and recently founded SearchQuant, put together the event. They hope it represents the beginning of a movement, bringing more transparency and fairness to the process of equity compensation for start-up employees.

The launch was much bigger than the two had anticipated. They originally expected a couple of dozen attendees (start-up employees only, no founders or venture capitalists allowed), and had scheduled the meeting to be held in a downtown office. When RSVPs pushed 300, they scrambled to relocate it to the theater at a local high school. And the crowd of engineers, computer scientists, and business grads pretty much filled the joint.

They came because they had gotten raw deals from a start-up in the past, were in the process of negotiating employment contracts with start-ups right now, or are working for most established companies but hoping to join start-ups in the future. In any case, they came because they feel lost when they try to understand the way start-ups compensate employees.

Indeed, Zaharias said, according to a 2011 survey, two-thirds of start-up employees don’t know the number of shares their companies have outstanding—which means that even if they know the number of shares they are entitled to, they have no idea how to value those shares.

That may not sound like a big deal to someone working at a traditional company, who might think something along the lines of “they get the stock for free, so what are they complaining about?” But start-up equity doesn’t come free—it comes in place of traditional salary. Start-up employees sacrifice current income to make a bet on the future, but, as Zaharias and Russell pointed out, the dice are often loaded. Even if employees know how much equity they have when they sign on, that number changes as more stock is issued. In addition, people can be fired just before they vest or right after a sale in order for companies to recapture equity, and companies can give themselves the right to repurchase shares at an “official” valuation that is actually much less than the company is worth.

Zaharias and Russell urged the audience to ask questions before they join start-ups and to keep asking questions over time to make sure they understand the potential value of their equity, which can change.

“A CEO I met the other day,” Zaharias reported, “said ‘I’ve hired over 1000 people in 20 years and not one of them has asked all the right questions.’ Another CEO said, ‘If they don’t ask for equity information, I’m not gonna tell them.’”

When Zaharias and Russell opened the floor to questions and war stories, dozens of hands flew into the air, confirming that start-up equity is anything but an open book.

- “What if you get hired and shares get diluted? How can you protect your original equity?”

- “I am now a non-employee so I don’t know what’s happening in the next round. How do I find out?”

- “A company I worked at was sold to a private company; employees were allowed to take exchange stock for the company that acquired it or take the cash value at $5 less per share. But the law said we couldn’t take the stock because we weren’t accredited investors.”

- “When I was negotiating for options I had no idea what was standard. I’m told VCs have schedules as to how much you should get at what level at what stage—how do you find out about that?”

- “Is it true that a private company can, before acquisition, fire half the staff and issue a gazillion new shares?”

- “I joined a company a couple of years back, I knew the CTO and trusted him, I asked the number of outstanding shares, he gave me a number. It wasn’t until later that I found out that the number was off by an order of magnitude and I got one tenth the value I’d thought.”

The crowd had a lot of questions, and Zaharias and Russell had few answers, except ask your employer until you understand, and then ask again every time something changes at the company, another investor comes in, say, or a potential buyer appears on the horizon. But they do believe the situation can be made better—a lot better—by starting a movement “that forces VCs and founders and everyone else to understand that this benefits everyone, that it will make sure that we (start-up employees) won’t bleed away to massive companies because there’s too much risk” in start-ups.

The two have launched a wiki site, Startuprights.org, and are using it to develop a Startup Employee Equity Bill of Rights. So far, the draft lays out five basic rights—the right to know (the company’s capitalization and valuation), the right to value (not limited by unreasonable vesting terms), the right to hold earned equity (preventing the company from repurchasing or otherwise seizing vested equity), the right to tax benefits (not being responsible for tax penalties incurred because of the company’s negligence), and the right to enforce (with access to the information to make that possible).

They’re also using the site to share war stories, like:

“An early employee of a start-up left the company ownership of his vested shares. When the company was acquired three years later, he discovered in the fine print that he had no right to his share of the merger proceeds because he was no longer with the company. In other words, his vesting was infinite because he had to stay with the company to have any right to value.”

and

“Employees who left or were terminated by Skype before its acquisition by Microsoft thought they owned their vested shares and would share in the $8.5 billion purchase price. But under their stock option agreements, the company had the right to repurchase the shares from the employees at the exercise price. This gave those former employees $0 of the $8.5 billion purchase price.”

Going forward, Zaharias and Russell hope the people who attended Friday night's organizational meeting contribute to the wiki to flesh out the bill of rights, begin using the document themselves in equity negotiations, and spread the word to other current and potential start-up employees. If enough people do this, Zaharias is optimistic that the culture will change until transparency and fairness is the rule rather than the exception. “We need,” he says, “to have a Rosa Parks moment and say we have these rights and we are going to assert them.”

Follow me on Twitter @TeklaPerry

Tekla S. Perry is a senior editor at IEEE Spectrum. Based in Palo Alto, Calif., she's been covering the people, companies, and technology that make Silicon Valley a special place for more than 40 years. An IEEE member, she holds a bachelor's degree in journalism from Michigan State University.