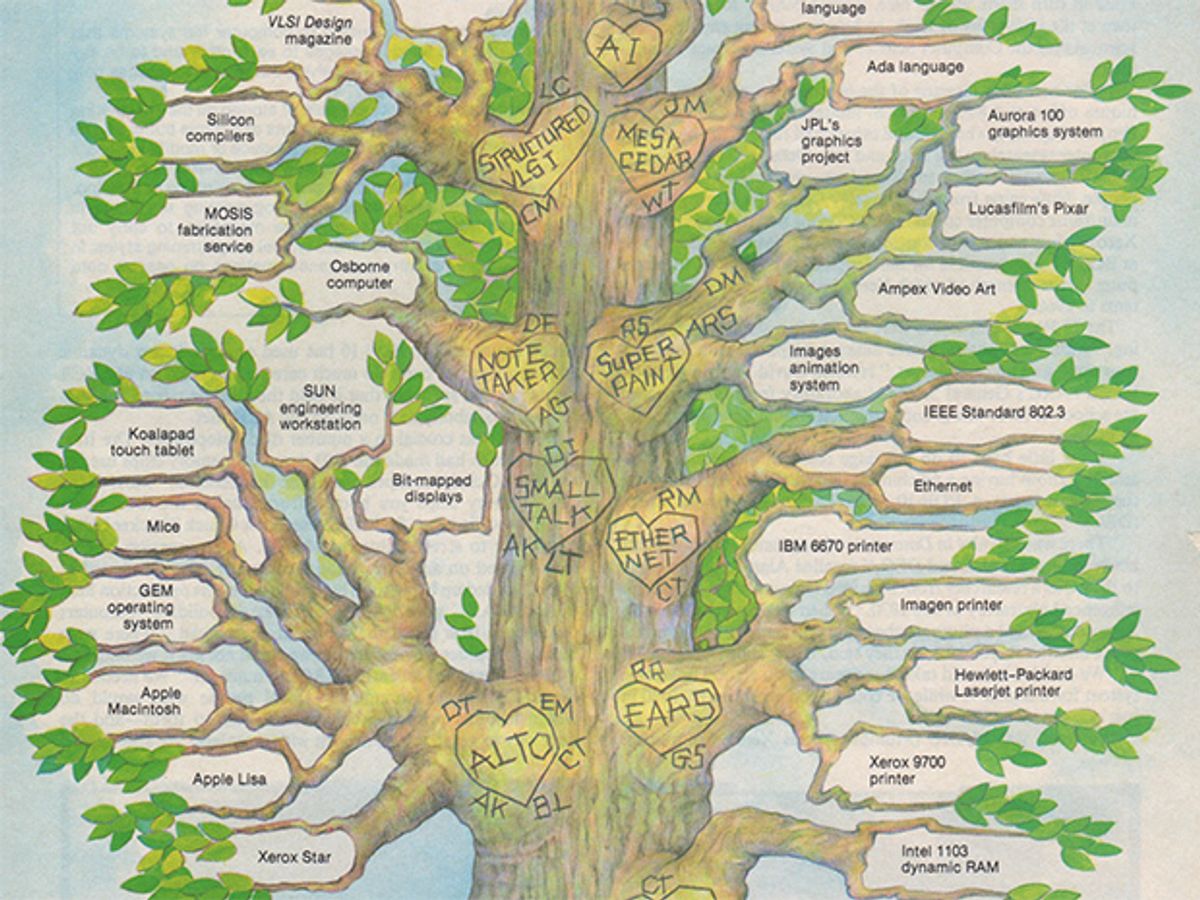

Xerox Palo Alto Research Center, birthplace of windowed displays, today’s word processing systems, Ethernet, laser printing, and, oh yeah, personal computing, celebrates its 40th anniversary this week. I’ll be attending the festivities tomorrow, and taking a walk down a memory lane of my own.

It was 1985. The innovations listed above had started to make it out of Parc and into the wild, as had word that this little research center was an amazing place. A cohesive story of what exactly had gone on there in the 70s had yet to be told; books like Fumbling the Future had yet to be written.

Over at IEEE Spectrum, we’d long been interested high tech work environments. With psychologist Doug Carmichael, I’d worked on a series of articles in which we visited companies to conduct in-depth interviews with groups of engineers and scientists, then detailed the inside stories, warts and all. (We didn’t reveal the names of the companies.) We were also long interested in research labs, and the amazing technology evolving inside their walls.

So the story of Xerox Parc [PDF, 25 MB] was irresistible—a research lab with amazing technology that was reported to have an incredibly special work environment, including a room full of beanbag chairs used for meetings.

Fellow Spectrum writer Paul Wallich and I pitched an article on Xerox Parc to our editors. We got a green light, along with what today seems like a luxurious amount of time and print real estate—over a month for research and 13 magazine pages.

During that research month we scheduled a full week in California, planning to see that beanbag room and interview current researchers, former employees, and anyone else we could corner, finding out everything we could about what made Parc special.

The one thing we didn’t have was the official blessing of Parc executives. (It’s OK, we’re all friends now.) So on our first day in California, when we arrived at Parc for our first interview, scheduled directly with a researcher, we found the director of the public relations department waiting at the entrance. She blocked our entrance. Literally, spreading her arms in front of the glass doors.

Frustrated? Not exactly. Don’t forget, this was the age of journalism in the wake of Woodward and Bernstein and All the President’s Men. It was supposed to be confrontational. And we’d never had someone stand in front of a building and refuse us entrance before. This was fun!

Had the cell phone network existed at the time, we would simply have called the researcher and had him meet us out in the parking lot. Without cell phones, we retreated to our hotel to regroup, and hit the land lines to schedule interviews all over Silicon Valley—anywhere but Parc. (To our disappointment, none of the researchers suggested meeting in a parking garage.) As a result, we got some great insider stories, the kind that likely wouldn’t have been told in a more official environment. Like arguments over whether or not the computer mouse made any sense at all. Like the impression the “antisocial eggheads” from California made on east coast executives. Like the first time a portable computer was used in an airport waiting area, ever. We talked to the people who had made computing history and wanted the world to know it—Alan Kay, Larry Tesler, Bob Taylor, Chuck Geschke, John Warnock, Lynn Conway, Alvy Ray Smith, Charles Simonyi, Bert Sutherland…the list goes on and on. And these folks would continue to make computing history again and again; meeting them so long ago, and in such a compressed period, was amazing.

So happy anniversary, Parc, and thanks for the memories. (Though I never did get to see that beanbag room.)

That article, “Inside the Parc: the ‘information architects’” [PDF, 25 MB] appeared in the October 1985 issue of IEEE Spectrum, and is available for download here.

The illustration, above, from the article, was an original watercolor painted by California artist Marilyn Theurer. Theurer has her own place in computing history, having worked on graphic design for early video games.

Tekla S. Perry is a senior editor at IEEE Spectrum. Based in Palo Alto, Calif., she's been covering the people, companies, and technology that make Silicon Valley a special place for more than 40 years. An IEEE member, she holds a bachelor's degree in journalism from Michigan State University.