How to See the Unseen City

There’s even more under the streets than you think

In 1870, quirky inventor Alfred Ely Beach unveiled a 90-meter stretch of New York City’s first subway. In his mind, the future of urban transportation lay underground—in the form of a pneumatic train. Beach’s idea was to expand the then-operational pneumatic mail system—a network of underground tubes that used pressurized air to send mail zipping through the city—into human-size mass transit.

Beach’s vision was replete with grand pianos and lavish waiting rooms, as well as candelabra in each train car. But the unwieldy dynamics of large-scale pneumatics, coupled with rapid improvements in electrically powered trains, blew his subway plan into obscurity.

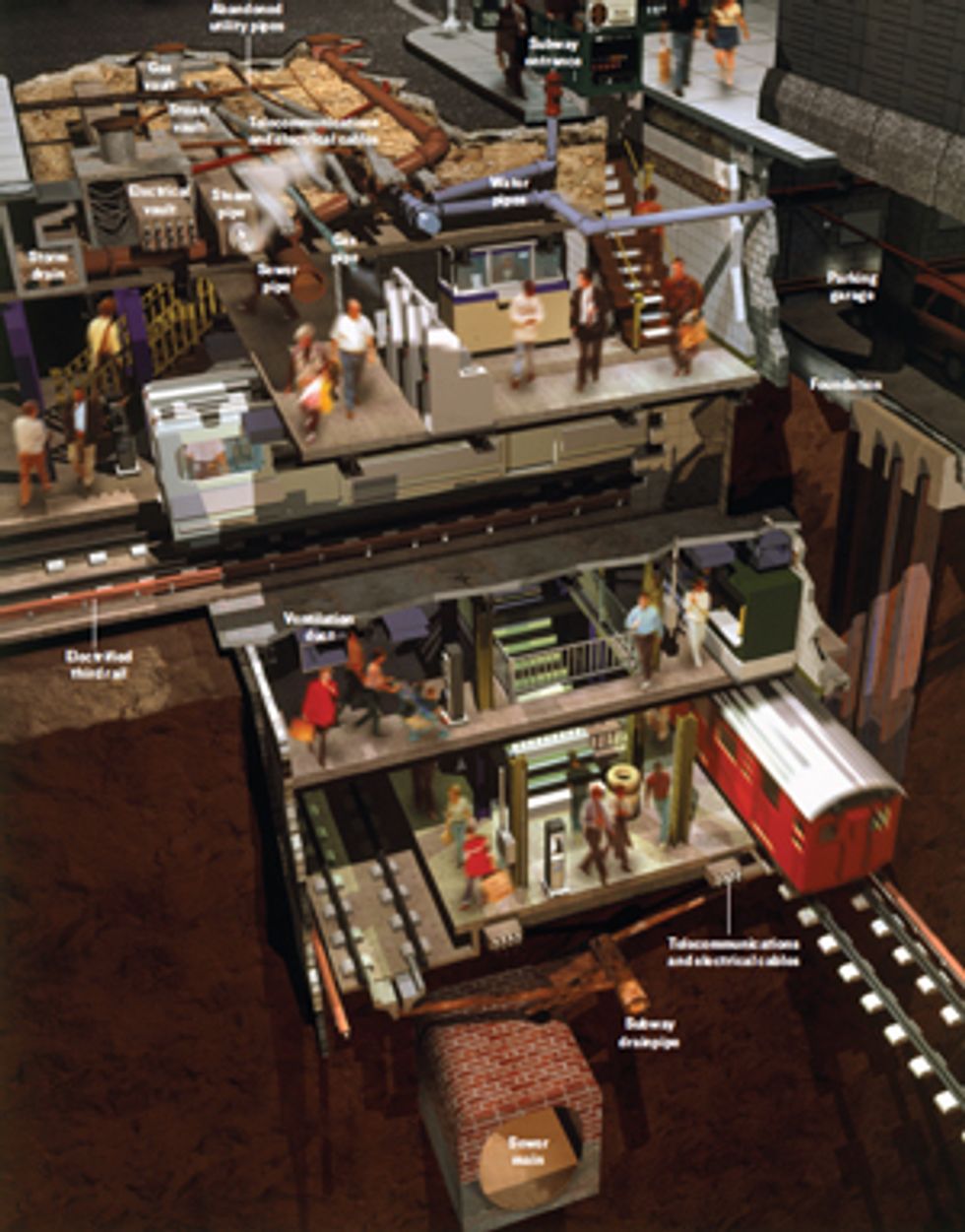

Today, few—if any—cities can rival New York in the density and complexity of its subterranean networks. New York’s urban underground contains a haphazard network of wires, cables, and water mains interspersed with a hodgepodge of corroded pipes and forgotten chambers. Long stretches of abandoned fiber-optic cabling are an unseen testament to telecommunications companies that installed lines in a frenzy in the 1990s, only to fold a few years later. The same fate has met portions of old water mains made from wood, many of which were decommissioned but never unearthed.

The depth at which each system is buried depends on the challenges of terrain. About 30 centimeters below the surface of New York lie 150 000 kilometers of electric cables, almost enough to wrap around the Earth four times. Down another 30 cm or so, 11 000 km of gas mains are buried, followed by some 10 000 km of water mains and 170 km of steam pipes. Subway tracks run from elevated platforms above ground level down to 60 meters below. Around 215 meters beneath the surface, water, pushed by gravity, flows from reservoirs in the north, and through giant tunnels into the city’s countless spigots.

To many city dwellers—and even to many city officials—underground infrastructure is both out of sight and out of mind. When inspecting pipes, the city commonly uses electronic listening equipment as its first line of defense. Maintenance workers dangle a microphone down a manhole and attach it to a water main to assess whether flow has been disturbed by a leak. More detailed checks are conducted from within a pipe, using what is essentially a video camera on wheels.

That equipment is an outgrowth of something London sewer workers used in the 1960s, when they wanted to prove to local authorities that a pipe was in urgent need of repair. They mounted a video camera on a wheelbarrow and rolled it through a brick sewer to create a visual record of the cracks.

In pipeline lingo, such tools are quirkily known as smart pigs. In addition to capturing digital video, a pig can perform radar and sonar scans above and below a water line, searching for indentations and holes in the walls as it rolls down a pipe. It records its location with odometer wheels and may be equipped with magnetic sensors to check for aberrations in metal pipes. Although deemed “smart,” the cylindrical device is only sometimes robotic and may be little more than a collection of sensors pushed along by fluid flow.

Fixing a break in a line, whether pipe or wire, also entails finding it—and knowing what else might lie above it. Although individual utilities each have approximate maps of their own infrastructures, few have coordinated closely with other agencies. Japan is the exception on the geospatial-information services (GIS) front, with a national mapping repository known as ROADIC. The underground mapping system consists of utility grids layered over a road map that utilities and builders consult before breaking ground. In the United States, moves toward centralized GIS plans for underground networks have been stymied by national-security concerns.

Those who dig a hole also run the risk of unearthing a bone or two. To reclaim valuable real estate, many cities had to exile their cemeteries, which moved their headstones outside city limits but often left the bodies behind. Municipalities around the world are now considering space-saving strategies, including burying people upright, mandating cremation, and building cemetery high-rises.

Vertical cemeteries by no means indicate that the underground frontier has been fully conquered. New York has been hollowing out another deep water tunnel to allow its existing two to undergo repairs, while Beijing, in anticipation of the 2008 Olympics, is expanding its subway system.

In Oslo, Norway, motivated by the frustrations of building on inhospitably hilly terrain, people have taken underground construction to new heights, or rather depths, and built all sorts of structures—such as power plants, an air-traffic-control tower, and a dairy processing plant—under the surface. As a result, some of the world’s most sophisticated air-circulation systems can be found in Oslo, as well as underground lighting that’s tweaked to mimic the movement of the sun throughout the day.

Wealthy cities are increasingly facing a premium on space. As metropolitan areas grow denser and richer, the urban underground is likewise poised to mirror the congestion above.

To see all of Spectrum’s special report on The Megacity, including online extras and audio and video exclusives, go to /moremegacity.