Do you know how much time your kids spent in front of a screen this weekend? Maybe one wrote a paper and the other saw a movie at the theater. Don’t forget the games on the tablet and the television shows. Oh, and the video chat with the grandparents. And social media on the phone while they were waiting for you. And the screens in the background that seem to be everywhere.

We’re woefully inaccurate at tracking such things. The older our kids get, the harder it is to keep tabs. And chances are, they don’t have a good barometer for it either. Yet self-reporting, despite its unreliability, is the main tool researchers use to gather data about screen time habits.

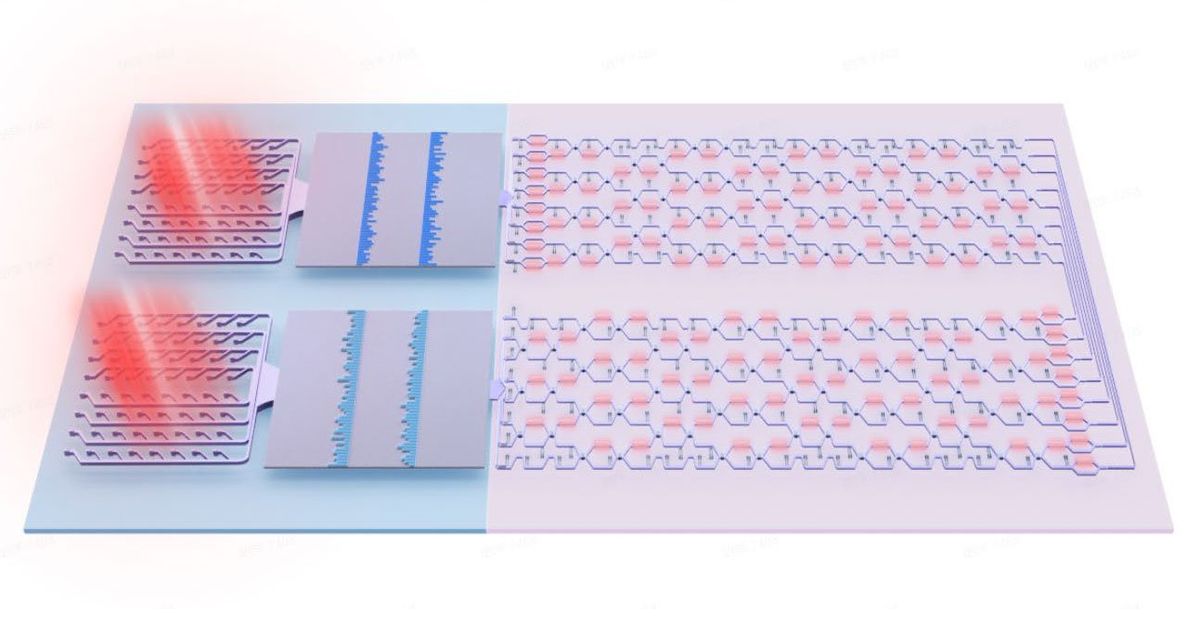

To address that problem, scientists at MIT have developed a new wearable tool to automate the tracking of screen time. The team, led by Richard Fletcher at the MITD-Lab, presented the wristband device last month at the IEEE Wireless Health conference hosted by the National Institutes of Health.

To develop the tool, the researchers took an off-the-shelf color sensor commonly used within televisions and other screens to calibrate color and brightness, and applied a learning algorithm that enabled them to figure out how to use that color data to determine when a screen was nearby. Light from screens tends to be dynamic, and the balance of colors is different than that typical of incandescent and fluorescent lighting. Using those signatures, the algorithm distinguishes screen light from ambient light. The off-the-shelf sensor component is sold by Hamamatsu.

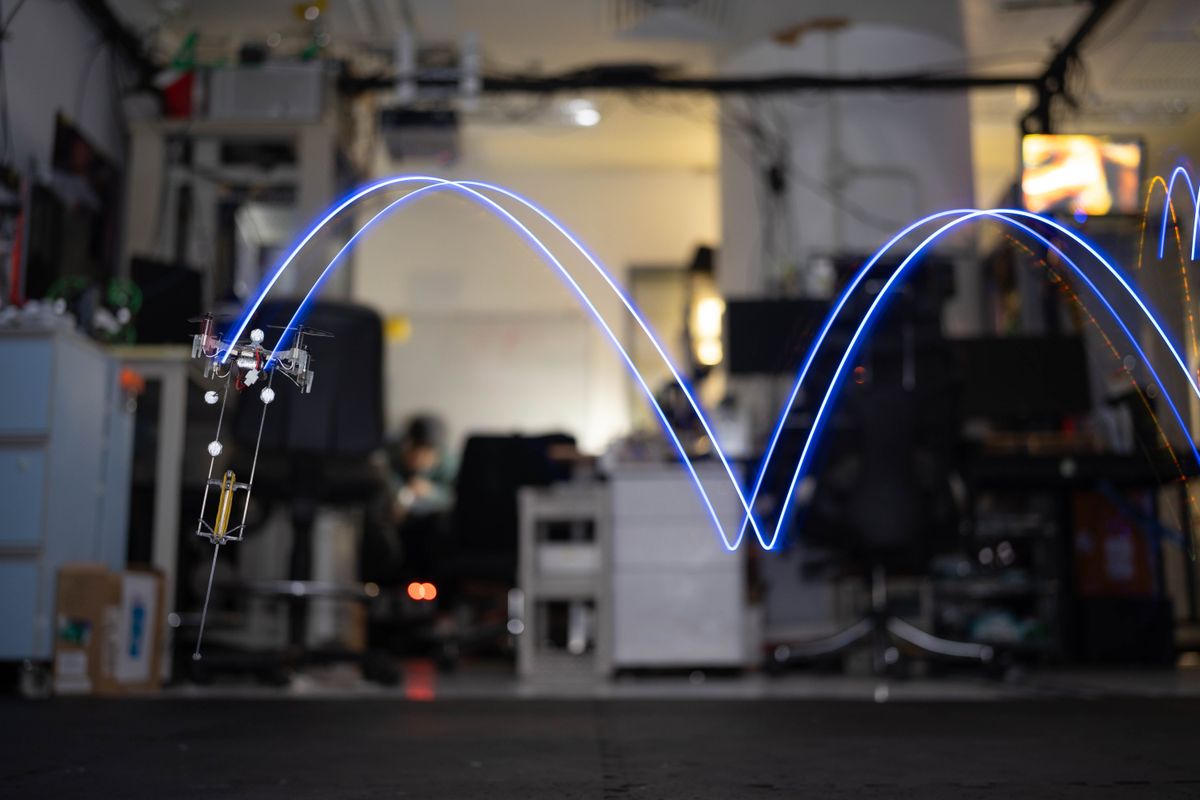

MIT’s device will be used by researchers at Massachusetts General Hospital in an upcoming clinical study on how children’s behavior contributes to high blood pressure, diabetes, obesity, and other related conditions. For that study, the sensors will be integrated into a wristband along with additional sensors that offer information about the children’s sleep and physical activity and other behavior.

A wristband isn’t the ideal place to put a sensor for catching light from a screen. (A kid might be curled up with his arm under a pillow.) But it was the best solution for reducing the number of gadgets the children would need to wear for the study, says Fletcher. “It’s better than the standard,” he says. Self-reported screen time—which in clinical studies is often gathered in the form of questionnaires and interviews with subjects—is likely somewhere between 50 percent and 80 percent accurate, Fletcher says. In preliminary studies, the MIT device was shown to be 80 to 90 percent accurate, he says.

Researchers, in study after study, are concluding that screen time has major deleterious effects on health, particularly in children. Blue light from screens is known to alter our body’s natural clock and disrupt sleep. It can affect the production of certain hormones that play a role in diabetes, obesity, and food craving. The sedentary behavior that often results from excessive screen time has also been shown to lead to obesity and other health problems that trickle down from that condition. There are also impacts on children’s socio-emotional development. And, of course, screens can lead to bad posture—our neck and back problems attest to that.

It’s a wonder then, with so many scientists conducting studies on the effects of screens, that no automated tracking device exists. A couple of groups have developed wearable devices for measuring general light exposure. Phillips sells one called Actiwatch Spectrum, and the Renssalaer Polytechnic Institute has developed several varieties called Daysimeters. The devices are valuable for measuring overall light exposure from all sources, but are not capable of tracking a person’s screen viewing behavior. There are a number of tools, such as Screen Time Labs, that can be downloaded to monitor the use of a particular computer. But those would be limited to the devices to which they can be downloaded.

It would also be possible to design a radio frequency tagging system that can detect when a person is near a screen, the researchers note. But that would be expensive, and would require putting tags on every screen a person might encounter.

Fletcher says he would like to see his device applied in other studies involving screen time, or perhaps used as part of an intervention for people with depression or other mood disorders. It could also come in handy at home, for concerned parents who want some hard data to back up their concern that their kids are getting too much screen time.

Emily Waltz is a features editor at Spectrum covering power and energy. Prior to joining the staff in January 2024, Emily spent 18 years as a freelance journalist covering biotechnology, primarily for the Nature research journals and Spectrum. Her work has also appeared in Scientific American, Discover, Outside, and the New York Times. Emily has a master's degree from Columbia University Graduate School of Journalism and an undergraduate degree from Vanderbilt University. With every word she writes, Emily strives to say something true and useful. She posts on Twitter/X @EmWaltz and her portfolio can be found on her website.